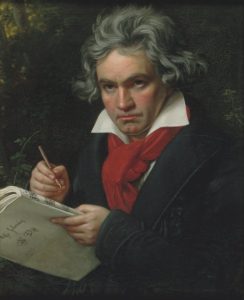

We mark the funeral of Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) on March 29, 1827 – 194 years ago today – in Vienna. It was a grand affair; tens of thousands of people lined the route of the funeral cortege. The funeral itself was attended by Viennese luminaries of every stripe, from the aristocracy to such composers as Franz Shubert, Johann Nepomuk Hummel, and Carl Czerny.

Speaking strictly for myself, Beethoven’s virus-compromised 250th birthday celebration continues to rankle. As I have previously stated (with tiresome regularity, I fear), it is my intention to continue that celebration, which should have concluded on the occasion of his 250th birthday on December 16, 2020, well into 2021. Just so: my Music History Monday and Dr. Bob Prescribes posts for the next two weeks will feature the B-man and his music.

This is all good.

Funerals in Vienna

The Viennese have traditionally had a “thing” about funerals. Far from being merely ritualized grief or memorials to those who have passed, traditional Viennese funerals – elaborate affairs with their grand caskets, long, parade-like processions and impassioned, theatrical eulogies – seem as much like Mardi Gras parades as they do “funerals.”

Vienna even has a funeral museum, called the Bestattungsmuseum Wien (meaning “Funeral Museum Vienna”) dedicated to the Viennese perspectives on death and Viennese funerary art, customs, and burial rites. (Vienna has, as well, an “Undertakers’ Museum” which documents Viennese society’s fascination – unhealthy fascination? – with death and burial. Just a tad kinky, I think.)

The Viennese obsession with a “schöne Leiche” (with a “beautiful corpse”) began immediately after the final defeat and exile of Napoleon in 1815 and the subsequent explosive growth of wealth in the Vienna-based Austrian empire. People saved for years and spent small fortunes on their funerals. They wanted to assure themselves a grand sendoff; they wanted to be remembered.

And remembered they were. For those who witnessed the spectacles of these funerals, they were an open-air party, a reason to sing and drink and debauch; to live and celebrate life to its fullest in the face of (inevitable) death.

According to Wittigo Keller, the curator of Vienna’s Funeral Museum, a Viennese funeral:

“was theater for the people. No ticket needed.”

Not coincidentally, the Vienna Funeral Museum is run by the city’s largest funeral company, Bestattung Wien.

While the company remains steeped in tradition, it is keeping up with the times. Among other things, in 2008 it began marketing a cremation urn shaped like a soccer ball to complement its line of traditional and more modern-shaped urns.

But in fact, only 20 to 30 percent of Austria’s dead are cremated. According to the Funeral Museum curator Wittigo Keller:

“We have room for decades more in the cemetery.”

That’s because Vienna’s principal cemetery – the Zentralfriedhof – is freaking huge. Opened in 1863, it covers 593 acres and is, in terms of its number of internments (over 3 million) the largest cemetery in all of Europe.

Beethoven’s own grave was moved to the Zentralfriedhof in 1888.…

Continue reading, only on Patreon!

Listen on the Music History Monday Podcast

Podcast: Play in new window

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Pandora | iHeartRadio | RSS | More