With our heads bowed and our hands on our hearts, we mark the death – 123 years ago today – of the pianist and composer Clara Wieck Schumann, who died of a stroke at the age of 76 on May 20, 1896.

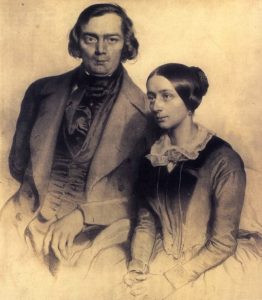

She was among the most outstanding pianists of her time, a child prodigy whose performances were described with awe by her contemporaries. She was a composer of outstanding promise, who – for reasons having to do with the world in which she lived and her own self-doubts – never had the opportunity to fulfill that promise. She was the compositional muse for her fiancé and husband, the great Robert Schumann, and the spiritual muse of her best friend, the even greater Johannes Brahms. And she was a survivor: someone whose life reads like some endlessly tragic Victorian novel, only without the “happy ending” tacked on at the end.

Honestly: whenever any of us get into one of those self-pitying funks (of which I am an especial virtuoso), during which we stand convinced that our personal lives represent the very nadir of human existence, I would recommend that we think of Ms. Wieck-Schumann and her life as an example of how very badly things can go if fate is not on one’s side. If such reflection doesn’t shame our own self-absorbed misery, frankly nothing will.

Clara Josephine Wieck was born on September 13, 1819 to Marianne Tromlitz-Wieck and Johann Gottlob Friedrich Wieck. Daddy was a creep: an uncompromising, unrelentingly ambitious autocrat who brooked no interference with his plans to make his little Clara the greatest pianist of her time. He was a horror to live with; in 1824, after five years of marriage, Clara’s mother Marianne could take no more and left him. Under Saxon law their three children were the “property” of the father, and so a distraught Marianne Weick had to be satisfied with the occasional visit and letter from her Clara.

Wieck controlled every aspect of Clara’s life in his efforts to mold her into a great pianist. In this Wieck was very, very lucky, in that Clara’s innate musical genius responded brilliantly to his training; she did indeed become a great pianistic prodigy.

In 1828, at the age of 9, Clara met another of her father’s students at a recital: an 18-year-old lapsed law student named Robert Schumann. Wieck’s “method” did not work for Schumann: the eight-hour-a-day exercise regimen Wieck prescribed for Schumann permanently ruined the ring finger on Schumann’s right hand, destroying his future as a professional pianist (though, gratefully, assuring that his energies were turned to composition).

Clara and Robert fell in love when she was 16 and he was 25. Wieck behaved like a madman for 5 years in his attempts to keep them apart, but to no avail, and they were married on September 12, 1840.

Clara did not know at the time that Robert was both bi-polar and syphilitic. Despite the fact that he was in his latency stage at the time they married – meaning that he was non-infectious and symptom free – it remains a miracle that he didn’t pass his syphilis on to her at some point, as they continued to reproduce well into his tertiary stage. (Their first child, Marie, was born in 1841; their eighth child, Felix – named for their dearly departed friend, Felix Mendelssohn – was born in June of 1854, four months after Robert’s mind had snapped and he had been institutionalized.)

Robert’s slow, excruciatingly painful descent into madness pushed Clara to the brink herself. His mind finally gave way on February 27, 1854, when he attempted suicide by jumping off a bridge in Düsseldorf into the Rhine River. He was rescued and hustled off to an asylum; Clara did not see him again until he lay on his deathbed in July of 1856, 2½ years later.

At the time of Schumann’s suicide attempt Clara was 34 years old; she was 5 months pregnant with her eighth child (Felix); she was the sole breadwinner for her brood; and after the devastating years of Robert’s illness and now his institutionalization, she hadn’t a clue as to how she was going to physically, spiritually, and financially survive. But survive she did, largely thanks to a family friend: the 20-year-old Johannes Brahms, who moved in with her and her children and who for 2½ years becoming a surrogate head-of-household and father to her children.

Johannes Brahms and Clara Schumann fell in love with each other in the fall of 1854, when he was 21 years old and she was 35. Whether they ever shared a bed (or couch or kitchen counter or billiards table) is still unknown and will almost certainly remain so. What we do know is that Brahms ended their “romance” not long after Robert’s death in 1856, and that that event broke Clara’s heart.

Clara’s life after Robert and Johannes was terribly difficult. Money was an endless issue and she had to concertize constantly to make ends meet. She was deeply conflicted about her profession verses her “duties” as a mother; and the guilt she felt about leaving her children for long periods with nannies took a heavy psychological and physical toll.

Clara’s children were an ongoing source of misery. Her son Emil, born in 1846, died after 16 months. Ludwig, born in 1848, manifested symptoms of mental illness from a young age; at the age of 22 he was diagnosed as having:

“An incurable spinal disease that presumably affected his brain.”

Clara wrote in her diary:

“I have not felt such pain since the misfortune with Robert. The nights were often dreadful, for hours I would see the poor boy before me, looking at me with his good, honest eyes.”

On the advice of doctors, Clara had Ludwig committed to an asylum in 1871. She visited him there twice – only twice – once in 1875 and then again 1876. He begged her to take him home. It was too much for Clara; she could not face her son and never saw him again even though she lived for another 20 years.

Clara’s son Ferdinand, born in 1849, became a morphine addict and predeceased her by 5 years, dying at age 42.

Felix, born in 1854 – the youngest of the children and everyone’s favorite – died of tuberculosis at the age of 24, predeceasing his mother by almost 18 years. Clara’s daughter Julie, born in 1845, was a radiant beauty of delicate health; she died of tuberculosis at the age of 27, predeceasing her mother by 24 years.

No wonder Clara wore black for the rest of her life: she never stopped mourning her dead. Proud, dignified, forced to bear extraordinary pain throughout her adult life; suffering, in her last years from debilitating joint and shoulder problems that forced her to retire from the stage, photos of the elderly Clara reveal a face and a spirit well described by the cliché: battered but unbroken.

It was in the early 1890s that Brahms – approaching his 60th birthday – became concerned (terrified would not be too strong a word!) that future generations were going to know more about him than he wanted them to know. So he began to recall from his friends the letters he had written them over the years. In no case was this more gut-wrenching than it was with Clara, who knew Brahms intended to destroy them. She begged Brahms to let her save just a few of his letters, but he refused. She returned them all, and this unique correspondence, a veritable four-decade eyewitness history of Europe and European music, was consigned to the flames, just like that.

Destroy the written evidence though he did, we know that Brahms loved Clara. For all their ups and downs, they rarely went more than a few weeks without seeing each other. He was, as we previously observed, a surrogate father to Clara’s children. He even fell in love with one of them – Clara’s daughter, Julie. But Brahms could never (and would never) declare his love for Julie; first, because it would have destroyed Clara, and second, because in Brahms’ mind it would have been tantamount to incest. Woody Allen he was not.

Brahms suffered deeply from the illnesses and deaths of Clara’s children. In particular, Felix Schumann’s wasting away from Tuberculosis broke his heart. In 1874, in response to Felix’s declining health, Brahms wrote Clara:

“I feel your pain and anxiety much too deeply to be able to express it to you in words. Let this deep love of mine be a comfort to you; for I love you more than myself, and more than anybody or anything on earth.”

Call their 43-year relationship what you will, it was the one true emotional anchor in either of their lives. For all Clara’s suffering, her moaning and sniffling and sobbing and flashes of white-hot anger at Brahms’ not-infrequent and titanic insensitivity, they could not live in a world without each other. And each of them knew it.

The news came to Brahms by telegram on May 20th, 1896 – 123 years ago today – from Clara’s eldest daughter, Marie.

“Our mother fell gently asleep today.”

Clara had suffered a devastating stroke on May 16; she lingered for four days and then died. Brahms was physically incapable of taking part in Clara’s funeral procession. He hid behind some large funeral wreaths and sobbed uncontrollably. He told the violinist Alwin von Beckerath:

“Now I have nobody left to lose.”

He followed Clara to the grave just 10 months later, at just before 9 a.m. on April 3, 1897.

Goodness; to have those letters.

For lots more on Clara Schumann and Johannes Brahms, I would humbly direct your attention to my Great Courses “Great Masters” biographies of Brahms and Robert and Clara Schumann.

Listen on the Music History Monday Podcast

Podcast: Play in new window

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Pandora | iHeartRadio | RSS | More