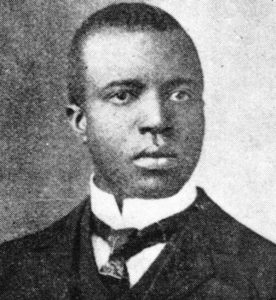

On April 1, 1917 – 102 years ago today – the American composer and pianist Scott Joplin died at the Manhattan State Hospital on New York City’s Ward’s Island, which straddles the Harlem River and the East River between Manhattan and Queens. He was 48 years old. During the course of his compositional career – which spanned the nineteen years from 1896 to 1915 – Joplin composed 44 ragtime works for piano, a ragtime ballet and two operas. (A musical “vaudeville act”, a musical comedy, a symphony and a piano concerto were purportedly composed as well near the end of Joplin’s life. These works were never published, and the manuscripts have, presumably, been lost, leading some to wonder whether they ever really existed at all.)

Embraced today as being among the greatest and most original of American composers; creator of the single most famous ragtime work of them all, Maple Leaf Rag of 1900; inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame in 1970; awarded a Pulitzer Prize in 1976; and featured on a first-class postage stamp in 1983; Joplin died in almost total obscurity there at the Manhattan State Hospital, which was then – with 4,400 beds – the largest psychiatric hospital in the world. He was buried in an unmarked pauper’s grave at St. Michael’s Cemetery in the East Elmhurst section of Queens, New York, not far from LaGuardia Airport. His grave was finally given a marker in 1974, the year that the movie The Sting – the score of which featured his music, most notably The Entertainer – won seven Academy Awards, including best picture and best score.

(That “best score” Oscar went to Marvin Hamlisch, which rubbed many a person’s rhubarb the wrong way. According to the American composer and jazz musician Gunther Schuller, who played a not-insignificant part in the ragtime-revival prior to the making of The Sting:

“[Hamlisch] got the Oscar for music he didn’t write (since it is by Joplin) and arrangements he didn’t write, and ‘editions’ he didn’t make. A lot of people were upset by that, but that’s show biz.”)

Joplin’s life reads like a Victorian novel in which the heroic principal character suffers one spectacular disaster/indignity after another until, finally – mercifully! – the chaos ends and that principal character lives happily ever after. The difference between Victorian fiction and Joplin’s reality is that the disasters never stopped, and that the end of his life was as terrible as anything that preceded it.

He was born in either Texarkana or Linden Texas, the second of six children. His father, Giles Joplin, was an ex-slave from North Carolina who worked as a laborer for the railroad; his mother, Florence Givens, was a freeborn Black American from Kentucky who worked as a maid. Though Scott Joplin celebrated his birthday on November 24, the actual date of his birth is unknown; it was sometime between late 1867 or early 1868.

Early on, the Joplin family moved to Texarkana, Arkansas, where Scott grew up. As a young child he received a rudimentary music education from his father (who played the violin) and his mother (who sang and played the banjo). The child showed tremendous promise as a musician, to the degree that his mother was convinced that he had a professional career in front of him. According to Joplin biographer Susan Curtis, Florence Joplin’s ambitions for her son played a major part in the breakup of her marriage when, sometime in the early 1880s, Giles Joplin left his family for another woman.

According to a family friend:

“the young Joplin was serious and ambitious, studying music and playing the piano after school.”

Scott’s talent notwithstanding, his family was destitute, and there was no money for music lessons. Enter Julian Weiss, a German-born Jewish “music professor” who had settled in the area back in the 1860s. Impressed by Joplin’s talent and promise, Weiss took him on as a student; he helped Florence Joplin acquire a piano and taught Scott free of charge for five years, from the time he was 11 to 16 years old.

Joplin never forgot Weiss and showered him with gifts when he achieved fame as a ragtime composer.

(We cannot help but be reminded here of Louis Armstrong, who at the age of 6 went to work doing odd jobs – there in his hometown of New Orleans – for a family of Lithuanian Jews named the Karnoffsky’s. The Karnoffsky’s took the child into their home and treated him like a member of their family. Writing in his memoir Louis Armstrong + the Jewish Family in New Orleans, La., the Year of 1907, Armstrong described the simpatico he felt for the Karnoffsky’s:

“I was only seven years old, but I could easily see the ungodly treatment that the white folks were handing the poor Jewish family whom I worked for.”

The patriarch of the family, Morris Karnoffsky, helped young Louis purchase his first cornet. Such was Armstrong’s gratitude to the Karnoffsky’s that he wore a Star of David pendant around his neck for the rest of his life.)

Scott Joplin took to the road as a pianist in the late 1880s. Not much is known about his movements at the time, though we do know that the opportunities for a Black American pianist were, shall we say “limited”: one either played in church or in brothels/saloons/road houses. Joplin opted for the latter, performing syncopated, pre-ragtime, so-called “jig music” in the various red-light districts that dotted the mid-South.

The single event credited with “creating” ragtime was the Columbian Exposition of 1893: the Chicago world’s fair that celebrated the quadricentennial – the 400th anniversary – of Christopher Columbus’ presumed “discovery” of America. Black American musicians from all over the south and Midwest flocked to the Exposition, where they performed in the saloons, cafés

Scott Joplin performed at the Exposition and was swept up in the ragtime craze. In 1896 he composed and had published his first ragtime-inspired works. In 1899, while living and playing piano in Sedalia, Missouri, he composed his fifth piece. Dedicated to the “Maple Leaf Club” – a black dance club there in Sedalia – he called it Maple Leaf Rag, which almost overnight became the musical and structural model for many thousands of the rags that were to follow.

Maple Leaf Rag was “purchased” there in Sedalia by the musical instrument dealer John Stillwell Stark (1841-1927) on August 10, 1899. Stark paid Joplin $50.00

What followed over the next 15 years were Joplin’s compositional “salad days”, crowned by the composition of his ragtime opera Treemonisha in 1911. All good, yes? Unfortunately, Joplin’s private life was, increasingly, filled with heartbreak.

In 1899, he married a woman we only know as “Belle”. They moved to St. Louis in early 1900, where Belle gave birth to a daughter. The child died within just a few months, putting an insurmountable strain on what was already a difficult marriage (we are told that Belle had no interest in music in general and her husband’s in particular; yes, that will do it!). The couple soon separated and divorced.

In June 1904, Joplin gave marriage another shot. His blushing bride was the young woman to whom he had recently dedicated his rag “The Chrysanthemum”, a Little Rock, Arkansas native named Freddie Alexander. Alas, poor Freddie died but weeks later, on September 10, 1904, due to complications from a cold.

(Joplin’s next published work, a concert waltz entitled Bethena, bears a cover photo of an unidentified young woman wearing what appears to be a wedding dress. The speculation – unproven – is that it is a wedding picture of none-other-than Freddie Alexander, for whom Joplin grieved long and hard.)

We need to know that by every account that has come down to us, Scott Joplin was an exemplary man. According to Edward Berlin, whose book King of Ragtime: Scott Joplin and His Era (New York: Oxford, 1994) remains the primary Joplin biography:

“As a person, he was intelligent, well-mannered and well-spoken. He was extremely quiet, serious and modest. He had few interests other than music. He was not good at small talk and rarely volunteered information but if a subject interested him, he might become animated in his conversation. He was generous with his time and was willing to assist and instruct younger musicians. He had a profound belief in the importance of education.”

Fate was not even close to being done with Scott Joplin. Soon after Freddie Alexander’s death, he organized a 30-person opera company to perform – on tour – his opera A Guest of Honor, about the famous (and, at the time, controversial) White House dinner hosted by President Theodore Roosevelt in honor of Booker T. Washington. While on tour in either Springfield, Illinois or Pittsburg, Kansas, someone stole the box office receipts. Joplin was caught short: he couldn’t meet his company’s payroll or pay the boardinghouse where the company lodged. His belongings were confiscated, including the only extant copies of the score and parts to his opera, which were never seen again.

Joplin’s next opera – Treemonisha – suffered an even harsher fate: that of total indifference. Believing it to be his masterwork, Joplin bankrupted himself trying to get it produced and published. Finally, in 1915, in one last desperate effort to have it produced, he organized what amounted to a reading, which was held in a rehearsal room in Harlem for a small audience that included potential backers. The reading was a disaster, and the audience – including the potential backers – simply walked out. (For our information, Treemonisha received its rather belated premiere on January 27, 1972, in Atlanta, as a joint production of the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra and Morehouse College, conducted by Robert Shaw.)

Joplin was crushed by Treemonisha’s failure. He suffered a breakdown from which he never recovered, because even as these events unfolded, he was descending into madness, the result of tertiary syphilis. In January of 1917 he was committed to the Manhattan State Hospital, where he died from syphilitic dementia some 10 weeks later, on April 1, 1917, 102 years ago today.

Taken any way we choose, Joplin’s death at 48 years of age was a tragedy of the first order.

For more on Scott Joplin and the revival of his music, please check out my Dr. Bob Prescribes post, which will appear tomorrow – on April 2 – on my Patreon subscription page, at Patreon.com/RobertGreenbergMusic.

Listen on the Music History Monday Podcast

Podcast: Play in new window

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Pandora | iHeartRadio | RSS | More