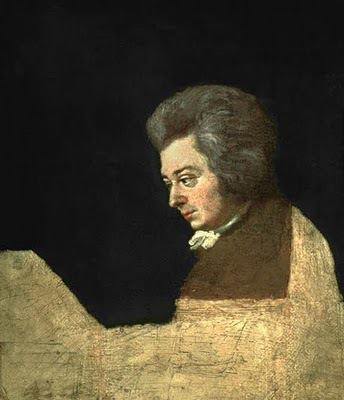

We mark the birth on January 27, 1756 – 264 years ago today – of Wolfgang Mozart.

There are certain dates that are so universally recognized that once invoked they can mean only one thing for a majority of people living on this planet. For example. Did we all know that January 1 is, among other things, Apple Gifting Day? It is also Bonza Bottler Day, Copyright Law Day, Ellis Island Day, Global Family Day, National Bloody Mary Day, and Public Domain Day. Did we all know that? And really, do any of us care? Because January 1 is New Year’s Day and every other observance shrinks to insignificance by comparison (excepting, perhaps, “National Bloody Mary Day”).

Despite the fact that December 25 is Constitution Day in Taiwan and National Pumpkin Pie Day in the United States, the mention of that date can mean only one thing in much of the world: Christmas Day.

May 1 is, in the northern hemisphere, May Day: a traditional celebration of spring. Planet wide, it is International Workers’ Day.

Since at least the fourteenth century, April 1 has been “international prank day”: April Fool’s Day.

From its beginnings as a Celtic harvest festival, Halloween (a.k.a. October 31, Hallowe’en, Allhallowe’en, All Hallows’ Eve, and All Saints’ Eve) has today become an international celebration, the promotion of which can be cynically attributed to a dark element within the international dental community, whose ministrations must repair the tooth damage perpetrated by all that ingested candy.

We must now acknowledge another date that can only mean one thing, a date that once uttered should be recognized by each and every one of us as representing something wonderful, something miraculous, a gift without which our lives would be bereft: the birth of Joannes Chrysostomus Wolfgang Gottlieb Mozart.

(We would also take a moment to acknowledge the horrific irony that January 27 is also both Auschwitz Liberation Day and International Chocolate Cake Day.)

Where do we start when talking about Mozart? His music is so consistently glorious, his life was so tragically short, and his impact on global culture so immense that he stands as a singularity even among the giants of Western art. And yet for all of his fame and visibility, there is no major composer whose life and personality are more shrouded in myth and mistruth than Mozart’s.

I’ve written extensively about the so-called “Mozart myths”: the half-truths and un-truths that have accreted over Mozart’s memory like guano on sea-side rocks. He was not the fair-haired, boy-god of music created by nineteenth century Romantic era mythologists. Neither was he an idiot savant or autistic, as some biographers have suggested. Nor was he – as has been claimed – “the Hegelian apotheosis of musical perfection taken to god’s bosom at 35, once all his musical branches had borne fruit, the Christ of music.”

For now, we are going to deal with the most outrageous and familiar of the Mozart myths, “familiar” because it was set-in-stone in our communal consciousness by that movie: Amadeus.

That Movie

Our most enduring image of Mozart today is the one we’ve received from Amadeus.

The movie was – and remains – excellent entertainment. It won eight Academy Awards in 1985, including best actor and best picture. It depicts Mozart as being a horse-laughing lout with the emotional age of a 12-year-old child.

For the record: that depiction of Mozart as being essentially nothing but a potty-mouthed punk is categorically, absolutely false.

The questions we must ask ourselves is why would the adult Mozart be portrayed in such a manner? And who should we blame for such a libelous portrayal? Should we blame Peter Shaffer, who wrote the screenplay for the movie based on his own stage play of the same title? Or should we blame the Russian playwright Alexander Pushkin, whose own play Mozart and Salieri provided the basis for Shaffer’s Amadeus?

No; let’s lay the blame where it belongs: at the feet of Mozart’s father, his sister, and his wife.

If it is true that the “victors” write the histories, it is also true that the living write the biographies.

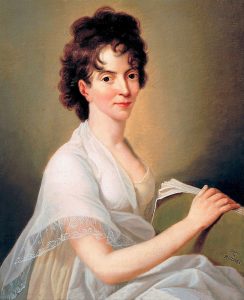

No one who knew Mozart in his lifetime wrote responsible accounts of him during his lifetime or after his death. Yes: Mozart’s widow Constanze “edited” a biography of her husband in 1828, by which time she had been spinning her dead husband’s memory for 37 years. And why would she do that?

Here’s why. It was well known at the time of Mozart’s death in December of 1791 that he and his wife were deeply in debt. They were both big spenders – often irresponsible spenders – and the years 1788, 1789, and 1790 saw Wolfgang’s income crater for reasons quite outside his control. After Mozart’s death in 1791, Constanze passed herself off as the blameless victim of her husband’s financial excesses. In 1794 – three years after his death – Mozart’s first biographer Friedrich Schlichtegroll wrote this:

“In Vienna he married Constanze Weber and found in her a good mother of [their] two children and a worthy wife who sought to restrain him from [his] many excesses. Despite a considerable income, he left his family nothing beyond the glory of his name.”

Who do we think fed Friedrich Schlichtegroll that story?

In 1856, Mozart’s first important biographer, Otto Jahn, continued to perpetrate the myth of Mozart’s childlike irresponsibility and Constanze’s ongoing sacrifice when he described Constanze as:

“a patient martyr, suffering from the thoughtlessness of a man of genius, who remained a child to the end of his days.”

To the day she died, Mozart’s sister Maria Anna claimed that her brother was just a big ol’ kid. In 1792, a year after his death, she wrote:

“Wolfgang was small, thin, pale. Apart from his music he was almost a child, and thus he remained: and this was the essential feature of his personality. He always needed a father’s, a mother’s or some other guardian’s care.”

Mozart’s father Leopold – who predeceased his son by 4½ years – went to his grave claiming his son was a child in a man’s body. Why would Mozart’s father and sister propagate that alternative fact: what were their motives? Like Constanze, their motives were personal enrichment and self-aggrandizement.

Mozart’s father Leopold – who predeceased his son by 4½ years – went to his grave claiming his son was a child in a man’s body. Why would Mozart’s father and sister propagate that alternative fact: what were their motives? Like Constanze, their motives were personal enrichment and self-aggrandizement.

Wolfgang Mozart was born on this day in 1756 in “salt city” – Salzburg – in modern Austria. His father Leopold was a violinist who worked for the Archbishop of Salzburg. Mozart’s mother, Anna Marie, served up seven children, only two of which survived their infancy: Wolfgang and his elder sister Maria Anna.

Two-out-of-seven: a tragic survival rate, but oh what survivors! By 1759 – when Wolfgang was three and Maria Anna was eight – Leopold Mozart had come to realize that arrayed around his family dinner table was a gold mine of talent, particularly the boy. Sickly and undersized though he was, Leopold referred to him as “[the] miracle which god let be born in Salzburg!”

Wolfgang was a miracle, and Leopold – as a professional musician and teacher – was in a perfect position to appraise, teach, and exploit his son’s talent.

This Leopold did. He became his son’s teacher, his ghost-writer, concert producer, travel agent, booking agent, public relations huckster, investment counselor, valet, and, in the end, oppressive tyrant.

From the time he was a toddler, little Wolfgang’s role was to “play” the part of a sweet, impossibly gifted child in order to pile money, fame, and social standing at his father’s feet. It was to the Mozart family’s advantage for Wolfgang to appear to be an “eternal” child, and to that end Leopold Mozart routinely lied about his son’s age, in order to make his abilities appear to be that much more “prodigious”. At some point the entire Mozart clan came to see Wolfgang as a permanent child. But he was not a “permanent” child; he grew up. But that didn’t stop his immediate family from continuing to consider him as being “the child”.

As a small child, young Wolfgang idolized his father. But even the most compliant children become surly with age (on this I can speak with the authority of experience), and by the time Wolfgang was an adolescent, Leopold could no longer count on his unqualified obedience. Leopold Mozart was nothing if not adaptable, and so over time his bullying took ever new forms, including harangues and guilt trips that would make even my Jewish mother blush, and no slouch was she. Leopold Mozart was the original tennis father and tiger mama, but nothing he did could prevent his son from growing up.

In May of 1781, completely against his father’s wishes, the 25 year-old Wolfgang quit his day gig in Salzburg and put out his shingle in Vienna. Completely against his father’s wishes he married a singer named Constanze Weber in 1782. (For this Leopold Mozart disinherited his son, thereby denying Wolfgang his share of the money he had earned during the concert tours of his childhood! The beneficiary of Wolfgang’s disinheritance? His sister: Maria Anna.)

But what really, really irked Leopold and his weasel of a daughter was how wrong they were about Wolfgang. Their predictions that he would crash and burn once he was on his own were completely wrong. Having settled in Vienna, Mozart quickly became a man about town: a celebrity whose activities were the stuff of gossip.

Mozart’s quick (though unfortunately temporary) success in Vienna was due to his work ethic, his perseverance, his entrepreneurial spirit and business savvy. He was a tireless worker. Between 1782 and 1785 he composed over 150 pieces of music which spanned every conceivable genre and style, from solo keyboard music and concerti to duos, trios, quartets, quintets, songs, arias, operas, wind ensembles and symphonies: something for everyone.

In a letter to his father dated March 4, 1784, Mozart listed 22(!) concerts he was slated to give:

“You must forgive me if I don’t write very much, but it is impossible to find time to do so, as I have three concerts coming up, beginning on the 17th. I have 100 subscribers already and shall easily get another thirty. As you may imagine, I must play some new works – and therefore I must compose. The whole morning is taken up with pupils and almost every evening I have to perform. Well, haven’t I enough to do?”

“Haven’t I enough to do?” Wolfgang was rubbing rock salt into his father’s suppurating emotional wound: “Look, pops, at what a success I am. And I did it all without you!”

It galled Leopold so! He was forced to recognize that he was not only wrong about his son, but that his son did not need him. And so he lashed out at Wolfgang; he called him a “child” and died an angry, embittered man. Maria Anna, ever the “good daughter”, continued to propagate the lies about the “child” Mozart until her death in 1829 (38 years after Wolfgang’s death), by which times the lies had become accepted fact. As for Mozart’s widow Constanze, who lived until 1842 (and thus outlived Mozart by 51 years!): rich from Wolfgang’s posthumous musical legacy, she could claim that it was her forbearance that allowed the “man-child” to create the extraordinary music he did, and she was thus morally entitled to the huge profits his music generated after his death.

All told, Mozart’s memory deserves better. A lot better.

Happy birthday, Maestro, and bless you for having existed.

For scads more on Mozart and his music, I would direct your attention to my website at RobertGreenbergMusic.com, where you can examine and download my numerous courses on Mozart, including surveys of his life, chamber music, and operas. And to encourage you to join me on Patreon.

Listen on the Music History Monday Podcast

Podcast: Play in new window

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Pandora | iHeartRadio | RSS | More