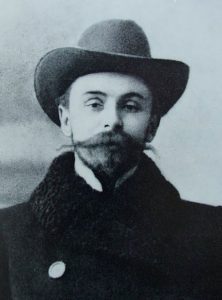

Alexander Scriabin (1871-1915) composed a total of ten numbered piano sonatas in the 21 years between 1892 and 1913. He composed, as well, an “unnumbered” piano sonata in E-flat minor in 1889, when he was 18 years old. These eleven piano sonatas form a virtual musical diary, and as such map Scriabin’s extraordinary artistic trajectory from the time he was a student at the Moscow Conservatory to the end of his all-too-short life, by which time he was no small bit loony (looners?).

As we observed in yesterday’s Music History Monday post, which celebrated the 148th anniversary of Scriabin’s birth, the man went through an early mid-life crisis in 1902 at the age of 30 that makes buying a Corvette and taking a girlfriend look like BUPKISS. He quit his teaching job, abandoned his wife and four children, took up with a former piano student of his named Tatiana Schloezer, immersed himself in an esoteric philosophy called “Theosophy”, and came to the conclusion that he was god. That’s what I call a mid-life crisis!

Theosophy and Revelation

The philosophy of “Theosophy” (I’m a poet and I’m unaware of the fact) that Scriabin went literally “crazy” over around 1902 considered visual and musical art to be vehicles for revelation: that is, art capable of imparting divine knowledge unmediated by words or the intellect.

Late nineteenth and early twentieth century Theosophy was characterized by three central beliefs.

Belief number one: that the cosmos consists of three interrelated elements, all of which are fully “alive”: nature, the divine, and humanity.

Belief number two: the creative impulse – and all the myths and symbols and sounds and images it employs – synthesizes nature, the divine, and the human into a singularity understood to be “the mind”.

Belief number three: the creative impulse gives humanity the ability to penetrate and become one with nature and the divine. The creative process gives humanity access to all levels of reality, “to co-penetrate the human with the divine and to bond to all reality and experience a unique inner awakening.”

Russia’s most important mystical-symbolist poet, Vyashaslav Ivanov (1866-1949) was a close friend of Scriabin and was downright jealous of the power of music to synthesize experience and reveal the deepest truths. Ivanov wrote:

“Where we poets monotonously blab the word ‘sadness’, music overflows with thousands of particular shades of sadness, each so ineffably novel that no two of them can be called the same feeling. [Music is therefore] the unmediated pilot of our spiritual depths, the most sensitive of the arts and inherently prophetic, the womb in which the Spirit of the Age in incubated.”

So back to Scriabin and his philosophical “epiphany”. The older he got, the more he came to believe that musical composition was not just a vehicle for self-expression but a vehicle for self-revelation. Indeed, by the last years of his life Scriabin had come to believe that his creative vision made him a virtual “god” among mortals. He kept diaries and notebooks in which he’d jot down his thoughts in a sort of “poetic prose” – some of which was quoted in yesterday’s Music History Monday – that seemed to indicate that by the end of his life he was a Brady or two short of a bunch.)

Scriabin, Sonata No 5 in F-sharp major, Op. 53

Scriabin’s Piano Sonata No. 5 of 1907 is a work of “superlatives”. It is the most frequently recorded of his ten piano sonatas. The great Soviet pianist Sviatoslav Richter once described it as the most difficult piece in the entire piano repertoire. At the time he finished writing it, Scriabin himself considered it the best piano piece he had ever composed. … Explore the piece, and Dr. Bob’s Prescribed recording, only on Patreon!