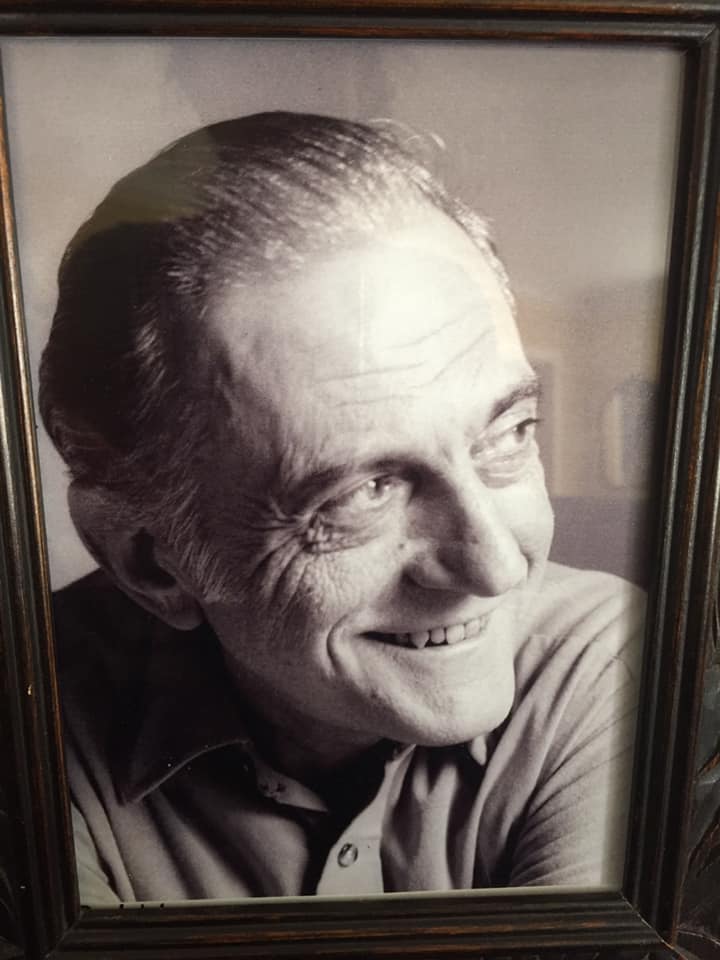

Let’s say it upfront: Salvatore (“Sal”) Joseph Mosca (1927–2007) is the greatest jazz musician you’ve likely never heard perform. Readers of my posts have heard of Maestro Mosca, as I’ve mentioned him repeatedly as being among my favorite, best-of-the-best jazz pianists ever. But I would hazard to guess that the vast majority of you have never actually heard him play.

That will all change during the course of this post.

I would tell you that Sal Mosca has inspired me to do something I never, ever, have otherwise done, and that is to write reviews of his albums on Amazon. I have written and posted only two reviews on Amazon, both of them dealing with Mosca albums. One of those review is spectacularly positive; the other equally negative. The positive one deals with one of the prescribed recordings” Too Marvelous for Words. The negative one deals with an album that should never have been released.

Writing under the nom-de-plume of “RMonteverdi”, here are those two reviews:

One Of The Very Best At His Very Best

“Sal Mosca was without any doubt one of the greatest improvising musicians who ever lived, and this fantastic five-cd set shows him at the very top of his game. Recorded live in June of 1981 during a series of solo concerts in the Netherlands, the tapes containing these performances were discovered in Mosca’s studio only after his death in 2007. Well, talk about finding 1000 shares of Berkshire Hathaway, Inc. in your grandfather’s sock drawer: these recordings are a treasure and their discovery after 26 years is something of a miracle. Mosca’s playing is impossible to categorize. He could play in any style; he was a brilliantly inventive harmonist; his solo lines are crystal clear and diamond hard. One of the most astonishing things about Mosca’s playing is his willingness to take risks: abruptly changing tempo, texture and style; playing left-handed solos; substantially elongating phrases or even single measures; all the while using the entire keyboard and playing with irrepressive joy. A spectacular set.”

Conversely, when the good people at Zinnia records released an album entitled “Thing-Ah-Majig” after Mosca’s death in 2007, my unhappiness with the release knew few bounds. Here is what I wrote:

“I don’t get it; I don’t get it at all. What compelled the folks at Zinnia Records to [make and then] release this album? It couldn’t have been the money; it’s hard to believe that this album came close to breaking even with production costs. Was it to honor and celebrate a legend, Sal Mosca? If so, it fails completely: in fact, it only denigrates and diminishes the legend. Was it [made] to make a sick, emphysemic, 77-year-old pianist feel he still had something to live for, something to contribute? Perhaps. But for a pianist as under-recorded as Mosca, an album like this one can do nothing but harm his legacy.

I first heard Sal Mosca in 1972, when Lee Konitz gave me a copy of his recently released album “Spirits” (Milestone, 1971). It’s a killer album, and the duets between Konitz and Mosca are revelatory. I’ve been a Mosca fan since, buying up every recording I could find. For those interested, his solo album entitled “A Concert” (Jazz Records, recorded 1979 and released in 1990) contains some of the most extraordinary piano playing of any kind that I have ever heard. (Another recommendation: “In Antwerp”, Zinnia, 1992. Extraordinary, utterly singular solo piano playing; GREAT album.)

Which brings me back to the present album, “Thing-Ah-Majig.” It contains the worst piano playing I’ve ever heard on record. Mosca’s once brilliant technique is gone; his ideas are pedestrian at best though mostly they are just banal; his rhythmic sensibility is flaccid; his touch is shot. Yes, there are the briefest moments when a shadow of what Mosca once was emerges, but they do not last long. Meanwhile, the obscenely congratulatory liner note (by bassist Don Messina) compares Mosca to Tatum, Horowitz, Tristano, Armstrong, and Parker among others. Oh please.

I usually give away records and CD’s I don’t want. I will burn this one, as I don’t want anyone to think that this is how Sal Mosca really played.”

Okay, okay, I know I was sugar coating my displeasure; but still, I was deeply upset that the bassist Don Messina – who has been an indispensable champion of Mosca’s music in ways to be momentarily described – should have allowed such an album to see the light-of-day.

Mosca was born on April 27, 1927, in Mount Vernon, New York, a “inner” suburb of New York City in Westchester County, roughly 5 miles north-west of Manhattan. Having fallen in love with the boogie-woogie and stride piano he heard on his family’s player piano, Mosca began his formal piano lessons at the age of 12. Within three years – by the age of 15 – he was performing in local nightclubs. In order to appear to be 18 years old (the minimal age for someone working in an establishment that served alcohol), Mosca took to wearing a fake moustache. During World War Two, Mosca was a member of a United States Army Band. With the war over, he studied “classical” piano at the New York College of Music by day and hung out in the jazz clubs on Manhattan’s 52nd Street by night.…

Continue reading, only on Patreon!

Become a Patron!