I will be forgiven, please, the overtly autobiographical nature of todays post.

In a number of ways I was something of a late-bloomer as a musician. Sure, I started piano at a fairly young age and played the “classics” that come with piano lessons; yes, my grandmothers – one a professional pianist and the other a professional actress – exposed me to a wide range of piano music and orchestral music when I was growing up; and indeed, my father’s record collection was an unending delight. But what passed for my “music education” as a child was a slapdash affair, and in fact, I knew very little. When I got into jazz at the age of 14 (or so) I abandoned practicing my dead Germans entirely.

So when I went away to college and suddenly encountered kids who went to high school at Juilliard Prep; or had just returned from participating in the music camps/festivals at Aspen, Tanglewood, Graz, and Spoleto; and met classmates like Stefan Kozinski (1953-2014), who already had a thriving career as a professional organist and piano soloist, and Eric Moe (born 1954), who had memorized all of Beethoven’s music and could give you a proper opus number after maybe a five second excerpt, well, to say I initially felt a bit outgunned and outmanned is an understatement on the lines of Jeffrey Dahmer’s “I knew I should have flossed” when he was finally arrested.

I would observe, however, that being a late-bloomer has its advantages. It made me a much better and more sympathetic teacher, as I will always remember what it felt like not to know something that everyone else already seemed to know. It made me understand that we cannot be too quick in our judgments: everybody’s trajectory is different, and different people come into “their own” at different times. The old musical saw that “if a kid doesn’t have it by 14, he/she never will” is a crock of merde. In fact, one of the reasons I was not unhappy about resigning my tenure at the San Francisco Conservatory in 2001 was that I felt I was being expected to judge the professional potential of my students at far too young an age. If I had been so judged at 18 or 19, I’d be selling insurance today.

Another advantage of being a relatively late-bloomer is that I took nothing for granted, and thus many new musical experiences had the primal impact of revelation. Listening to Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring (Ernst Ansermet’s performance) for the first time early in the fall of my sophomore year and realizing when it ended that, based on the drool in my lap, I had forgotten to swallow for 35 minutes. Studying Brahms’ chamber music with Claudio Spies my junior year was like falling in love for the first time: a full body, full soul experience.

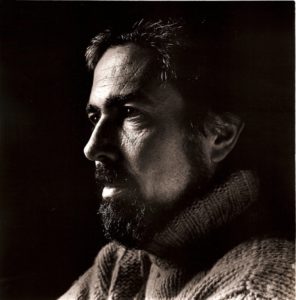

And then there is the album featured in this post. The album records the contents of a printed anthology of new music entitled New Music for Piano that was published in 1963. The anthology contains works by 24 U.S.-based composers, and represents as comprehensive a cross-section of mid-century musical styles and techniques as we will find anywhere between two covers.

I checked the printed anthology and Robert Helps’ recording out of the music library on a Friday in January 1975, during my junior year.

The cliché applies: I remember what happened as if it were yesterday.

I spent the weekend listening to the album and following along in the music. It was a bitterly cold, damp, foggy weekend: New Jersey weather at its finest. My roommates had better things to do than hang around our dorm suite, so I had the place to myself and could listen to the album to my heart’s content. And that I did, over and over again. … continue reading, and learn more, only on Patreon!