My Fair Lady is a fifth-generation work: an adaption of adaption of an adaption of an adaption, a musical that many top-end talents believed – for reasons we will discuss – could never be successfully written.

The original story of King Pygmalion comes from Greek myth and legend. It was the Roman poet Publius Ovidius Naso (known in the English-speaking world as Ovid; March 23, 43 B.C.E. – 18/18 C.E.) who gave the story form and substance in his Metamorphoses, which he wrote around 8 C.E.

(For our information: Metamorphoses is a Latin poem in 15 books. It’s a collection of myths and legends in which metamorphosis – transformation – plays some sort of role. The stories themselves are unrelated, though they are presented in chronological order, from the creation of the world (with the metamorphosis of chaos into order) to the assassination of Julius Caesar in 44 B.C.E. (and his subsequent metamorphosis from a mortal to a god).

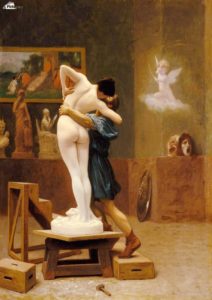

In Ovid’s version of the story at hand, Pygmalion is a sculptor. He carves a statue that represents what is, for him, the perfect woman. He names the statue Galatea and proceeds to fall in love with it/her. In answer to his prayers, the goddess Aphrodite/Venus brings her to life.

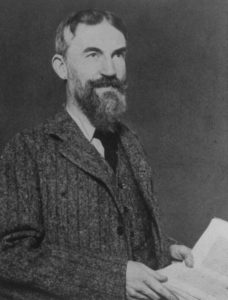

In 1912, the Irish-born playwright, critic, and polemicist George Bernard Shaw (who insisted on being called simply “Bernard Shaw”, 1856-1950) turned the story into a five-act play about language and the English class system. The story: an upper-crust, London-based “phonetician” (an expert in phonetics) makes a bet that by changing her speech, he will be able to pass a Cockney flower girl named Eliza Doolittle off as a duchess in six months. Eliza’s punishing training pays off. She is transformed into an elegant woman of sophistication and taste, only to discover that she no longer has a place in English society: she is, in fact, not a member of the upper class and no longer belongs to the lower class.

Shaw absolutely hated the idea of turning his plays into movies; at one point he famously turned down an offer from Samuel Goldwyn himself. So it remains something of a mystery as to why he assigned movie rights to a then almost unknown, Hungarian-born “producer” named Gabriel Pascal (1894-1954). Alan Jay Lerner told the story of Shaw’s and Pascal’s meeting (circa 1935) this way:

“A man rang the doorbell of Shaw’s cottage in Ayot St. Lawrence. When Shaw’s maid answered, the man said he was here to see Mr. Shaw. The maid said, ‘Who sent you?’

‘Fate sent me,’ said the man. Shaw heard this and came to the door.

‘Who are you?’ he inquired.

‘I am Gabriel Pascal. I am motion picture producer and wish to bring your works of genius to the screen.’

‘How much money do you have?’ said Shaw.

‘Twelve shillings,’ Pascal said, removing them from his pocket.

‘Come in,’ said Shaw. ‘You’re the first honest film producer I have met.’”

When Pascal left later that day, so the story goes, he carried with him a letter assigning him the motion picture rights to Shaw’s Pygmalion, Major Barbara, and Androcles and the Lion.… continue reading, only on Patreon!

Become a Patron!