Yesterday’s Music History Monday post marked the 116th anniversary of the premiere of Giacomo Puccini’s opera Madama Butterfly. The body of that post dealt with the charges of sexism, racism, and cultural appropriation leveled today at the opera, charges that have led many contemporary arbiters to demand that changes be made to the opera or that it be eliminated from the repertoire altogether.

As I rather forcefully observed in yesterday’s post, none of this changes the fact that Madama Butterfly is a masterwork of musical theater and deserves its place among the top tier of the operatic repertoire.

Unlike most other of Puccini’s operas, Madama Butterfly had something of a rough start; that story in a moment.

Giacomo Antonio Domenico Michele Secondo Maria Puccini was born in the Tuscan city of Lucca on December 22, 1858. He was born into a virtual dynasty of local musicians; members of Puccini family occupied the position of maestro di cappella (“master of music”) of the Cathedral of San Martino in Lucca for 124 consecutive years, from 1740 until 1864 (when Puccini’s father Michele, the current maestro di cappella, died prematurely at the age of 50).

Giacomo was groomed to enter the family profession and in the end outdid every one of his illustrious predecessors. He graduated from the Milan Conservatory in 1883, at the age of 25, and immediately set to work on his first opera. That opera – titled Le Villi (meaning, “The vengeful, vampire-like spirits of maidens betrayed by their lovers”) – was first performed in May 1884. Le Villi was successful enough to attract the attention of the Milan-based publishing house of G. Ricordi, which was not incidentally Giuseppe Verdi’s publisher. Casa Ricordi not only published Puccini’s Le Villi but the firm put Puccini under contract for an unspecified number of additional operas. Puccini, who composed slowly, didn’t complete his second opera – Edgar (meaning “Edgar”) – until 1888; it received its premiere in April of 1889.

Edgar was a flop, and for a while, it looked like curtains for Puccini’s still nascent compositional career as well. Ricordi’s investors wanted to drop Puccini like a hot raviolo (singular of “ravioli”), but the head of the company – Giulio Ricordi – believed in Puccini, telling his business associates that:

“if they wish to close the door on Giacomo Puccini, I myself will exit with him from the same door.”

Giulio Ricordi actually increased Puccini’s monthly stipend and told his people that if Puccini turned out not to be a “sound investment”, he – Ricordi – would repay the firm with money from his own pocket.

Heaven and posterity together bless Giulio Ricordi, because what was repaid in the end was his faith in Puccini. Puccini’s next and third opera, Manon Lescaut, received its premiere in Turin on February 2, 1893. Manon Lescaut was not just a smash hit; it vaulted Puccini to the top of the Italian opera industry. Almost overnight he came to be considered the most promising opera composer of his generation, Verdi’s successor “as the leading exponent of the Italian operatic tradition.”

That appraisal of Puccini came to be accepted as immutable fact with the production of his next two operas, La Bohème (1896) and Tosca (1900). And when Giuseppe Verdi died on January 27, 1901 at the age of 87, it was almost universally acknowledged that Puccini – who was 42 years old when Verdi died – was now the greatest living composer of Italian language opera.

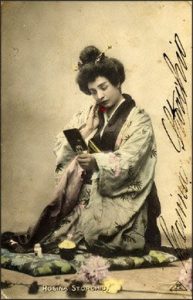

Given all of this, there was no reason to expect that the premiere of Puccini’s next opera, Madama Butterfly, scheduled for February 17, 1904 at Milan’s La Scala, would be anything less than a huge success. A killer-cast had been assembled, featuring the great Rosina Storchio as Cio-Cio San (“chō-chō” is Japanese for “butterfly”) and Giovanni Zenatello as Pinkerton. The set was designed by the well-known French scenic designer Lucien Jusseaume and the conductor was the highly respected Cleofonte Companini. The dress rehearsal had gone swimmingly. Puccini, confident of success, brought twelve guests with him to the premiere. A few hours before the opening curtain, he sent a note backstage to Rosina Storchio, in which he congratulated her in advance for what would be a “triumphant” first night.

Some triumph. The premiere turned out to be the worst fiasco of Puccini’s career.… continue reading and see Dr. Bob’s favorite recordings of Madama Butterfly, only on Patreon!