I am doing something here in this post today that I have only done twice before in the storied history of Dr. Bob Prescribes: I am recommending a recording for the second time. The other two times I did so were a matter of expedience, as I reran two posts back in early March immediately after my heart bypass surgery.

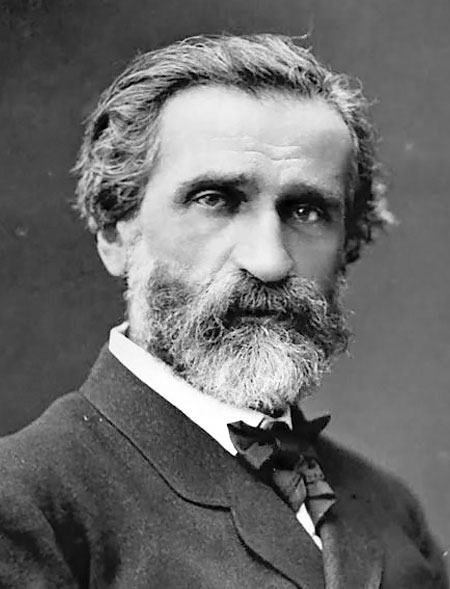

The issue today is not one of expedience but rather, of necessity. You see, Giuseppe Verdi’s String Quartet in E minor remains his least-known masterwork, and it deserves a much harder sell than it was given in what was a brief post back on March 10, 2020.

Yesterday’s Music History Mondayfocused on Verdi’s Requiem and its premiere on May 22, 1874, 149 years ago yesterday. What went unmentioned in yesterday’s post is that following the premiere of his Requiem, Verdi shocked the operatic world by announcing his retirement. It was an announcement that appeared to have aggrieved pretty much everyone on the planet with the notable exception of Giuseppe Verdi himself, who believed that with the composition of Aida (1871) and his Requiem (1874) he had freaking written enough.

Verdi and Retirement

In 1875 Giuseppe was truly at the very top of his game, in his absolute prime. So it did indeed come as a thunderbolt when, in late 1875, the 62-year-old Verdi did informed his nearest and dearest – his wife, his friends, and his publisher – that as a composer he was through, finito. After 24 operas and one requiem, after a lifetime of 16- to 18-hour days and impossible deadlines; harried constantly by librettists, producers, singers, critics, and conductors, Giuseppe Fortunino Francesco Verdi was done. When his great friend Clarina Maffei told him that he had a moral obligation to compose, Verdi wrote:

“Are you serious about my moral obligation to compose? No, you’re joking, since you know as well as I that the account is settled.”

He had been thinking about retiring for decades. In 1845 – at the age of just 32 – he was already fantasizing about his retirement. At that time he wrote to a friend:

“Thanks for remembering poor me, condemned to continually scribbling notes. God save the ears of every good Christian from having to listen to them! [You ask] how I am, physically and spiritually? Physically I am well, but my mind is black, always black, and will be so until I have finished with this career that I hate.”

But it wasn’t until 1876 – 21 years after having written that letter – that Verdi hung up his spurs and decamped to his estate in Busseto, in north-central Italy. To another friend he wrote:

“Now that I am not manufacturing any more notes, I am planting cabbages and beans, etc., but since this work is no longer enough to keep me busy, I have begun to hunt!!!! That means that when I see a bird, punf! I shoot it; if I hit it, fine; if I don’t hit it, [fine].”

No one was happy about Verdi’s retirement except Verdi. His wife Giuseppina was not at all pleased to have her cantankerous husband underfoot all day. But mostly, she understood that his retirement denied the world the further fruits of his genius. And in this, as we have already observed, Giuseppina was not alone.

In 1879 a plot was hatched with the intention of getting Verdi back to work. In the end, that plot (which was the subject of Dr. Bob Prescribes on August 6, 2019) was successful, and Verdi eventually composed two more operas: Otello (premiered in 1887) and Falstaff (1893).

But back, please, to Verdi’s compositional accomplishments immediately prior to his retirement, and his conviction that with those works, he had completed his mission as a composer. He believed that in 1875, with the composition of his three most recent works, he had – finally, and in fact – done it all. Yes, we know about Aida (of 1871) and its extraordinary Cairo premiere in December 1871 and its even more phenomenal Italian premiere in February 1872. And yes, we know about the equally successful first performances of Verdi’s Requiem (1874), first at the Church of San Marco in Milan on May 22, 1874, and then, three days later, on May 25, at Milan’s La Scala opera house.

But do we know about Verdi’s one-and-only extended instrumental work, a string quartet in E minor composed in 1873 in between Aida and his Requiem?

Generally speaking, as an audience, we do not know about the quartet. But soon enough, we will!…

Become a Patron!