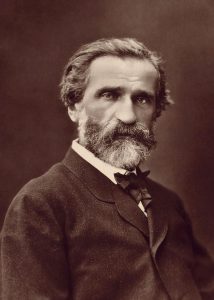

In June of 1870, the 57-year-old Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901) agreed to compose an opera for the brand-new Cairo Opera Theater. The Khedive Ismail Pasha of Egypt handled the negotiations personally; the opera was to celebrate nothing less than the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869. No expense was spared, either on the opera or on Verdi, who received the unheard-of commissioning fee of 150,000 gold francs: roughly $1,935,000 today!

Aida received its premiere in Cairo on December 24, 1871. The real premiere, as far as Verdi and the opera world were concerned, took place six weeks later, at La Scala in Milan on February 8, 1872. It was a triumph, the greatest of Verdi’s career to date; he received 32 curtain calls.

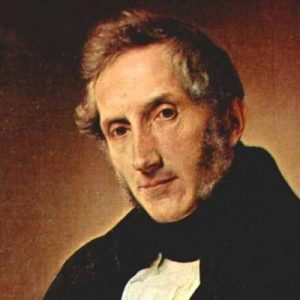

The only artist in Italy as popular and beloved as Verdi at the time was the novelist and poet Alessandro Manzoni (1785-1883). Manzoni’s most famous work is a novel entitled I promessi sposi (“The Betrothed”), which was written initially between 1821 and 1827; Manzoni completed the final, “definitive” version in 1842. Manzoni wrote this final version in what was (and still is) considered the stylistically superior Italian dialect of Tuscany. This final, “Tuscan” version of “The Betrothed” had a pivotal impact on the development of a consistent Italian prose style. At a time when the Italian peninsula boasted more dialects than varieties of pasta, Manzoni, more than any other single person, helped to popularize a single, ideal way of writing and speaking Italian, based on the dialect of Tuscany.

The importance of this cannot be overestimated. At a time when Italian patriotism and nationalism sought unification and a single, national identity, Manzoni’s work offered his nation a single, ideal, universally comprehensible Italian language. Manzoni came to be perceived – rightly – as not just the greatest Italian writer of his generation, but as a great Italian patriot as well. What Verdi did for his nation through the medium of opera, so Manzoni accomplished through the medium of literature: he inspired his country with a singular sense of national identity, pride, and nationhood through the medium of its oh-so-special language.

Verdi considered Manzoni to be a living saint, a man who combined extraordinary talent with great personal virtue and nobility. Manzoni died on May 22, 1873. The following day Verdi wrote to his friend and publisher Tito Ricordi:

“I am profoundly saddened by the death of our Great Man! But I shall not go to Milan, for I do not have the heart to attend his funeral. I will soon come to visit his grave, alone and unseen, and perhaps (after further reflection, having weighed my strength) to propose something to honor his memory.”

Ten days after Manzoni’s death, Verdi went the cemetery in Milan, stood next to his tomb, and formulated a plan. He returned to his suite at the Grand Hotel de Milan and wrote a letter to Ricordi, proposing that he compose a Requiem Mass for Manzoni, to be performed on the first anniversary of Manzoni’s death. Verdi’s intention was to write a work that would be performed in concert halls, with each such performance offering a proper memorial to the memory of Manzoni. … Continue reading about the development and background for Verdi’s Requiem and see Robert Greenberg’s prescribed recording, only on Patreon!