The backstory: in 1970, the 26-year-old Tilson-Thomas conducted Ruggles’ masterwork – Sun-Treader – in concert with the Boston Symphony Orchestra. (That performance was followed by Tilson-Thomas’ recording of Sun-Treader with the BSO recommended above.) At the time, Carl Ruggles was 94 years old and living in a nursing home in Bennington, Vermont (he died the following year, in 1971). We’ll let MTT tell the story from here:

“Ruggles, enigmatic and granitic man – how his music and spirit have haunted me. I first heard his music at age thirteen. The piece was Men and Mountains and I remember how stunning it was.

Years later I began to perform Mr. Ruggles’ music and to discover more of his remarkable testimony in each new performance. The fascination continued over the years and turned to awe and appreciation as through repeated performances I began to understand the depth of the music and power of its testimony. It was in this mood that following a performance of Sun-Treader with the Boston Symphony, I set out to meet Mr. Ruggles.

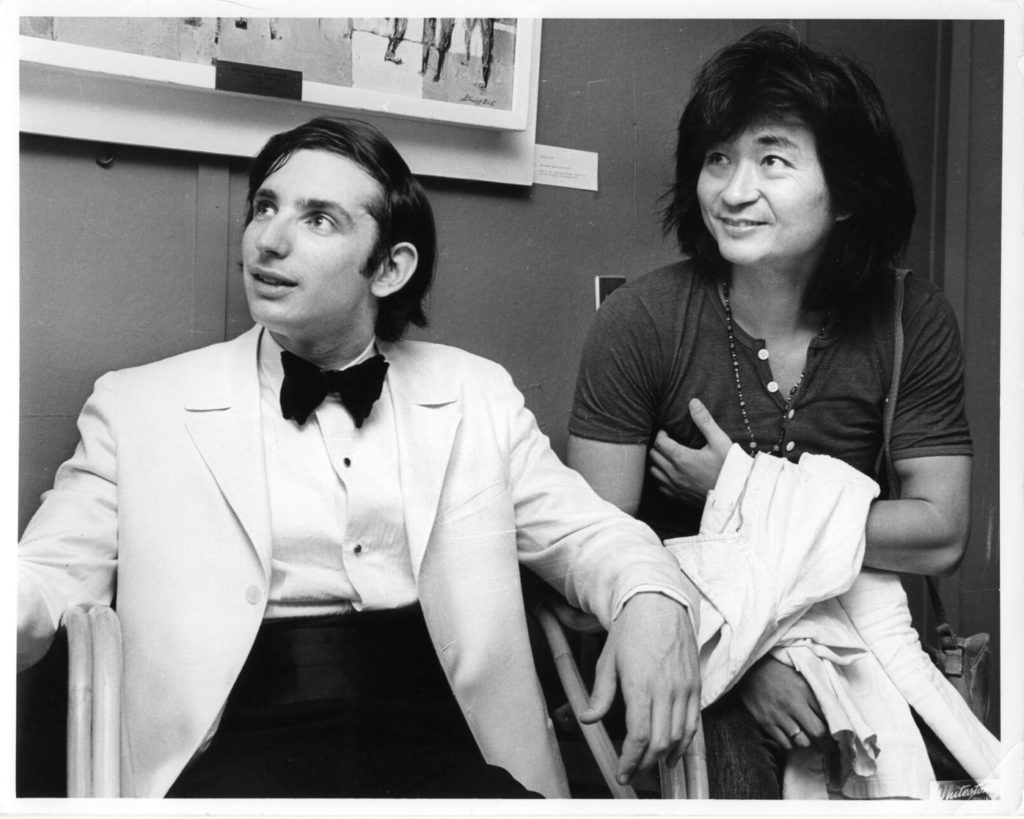

Syrl Silberman of WGBH-TV in Boston had worked on a film about him and had become friendly with the old man, who even then – in his nineties – was delighted to get a handsome young woman within grabbing distance. We drove up to the rest home where Mr. Ruggles, an old – and, some said, senile – man was living.”

Tilson Thomas continues:

“I had been told that Mr. Ruggles was inclined to be suspicious of new people and retreat behind the curtain of his infirmities. So Syrl and I just walked into his room and said ‘Hello,’ set up a tape recorder, put some light earphones on his old and shriveled head, cranked the volume up as high as possible and started to play an air-check of the performance of Sun-Treader.

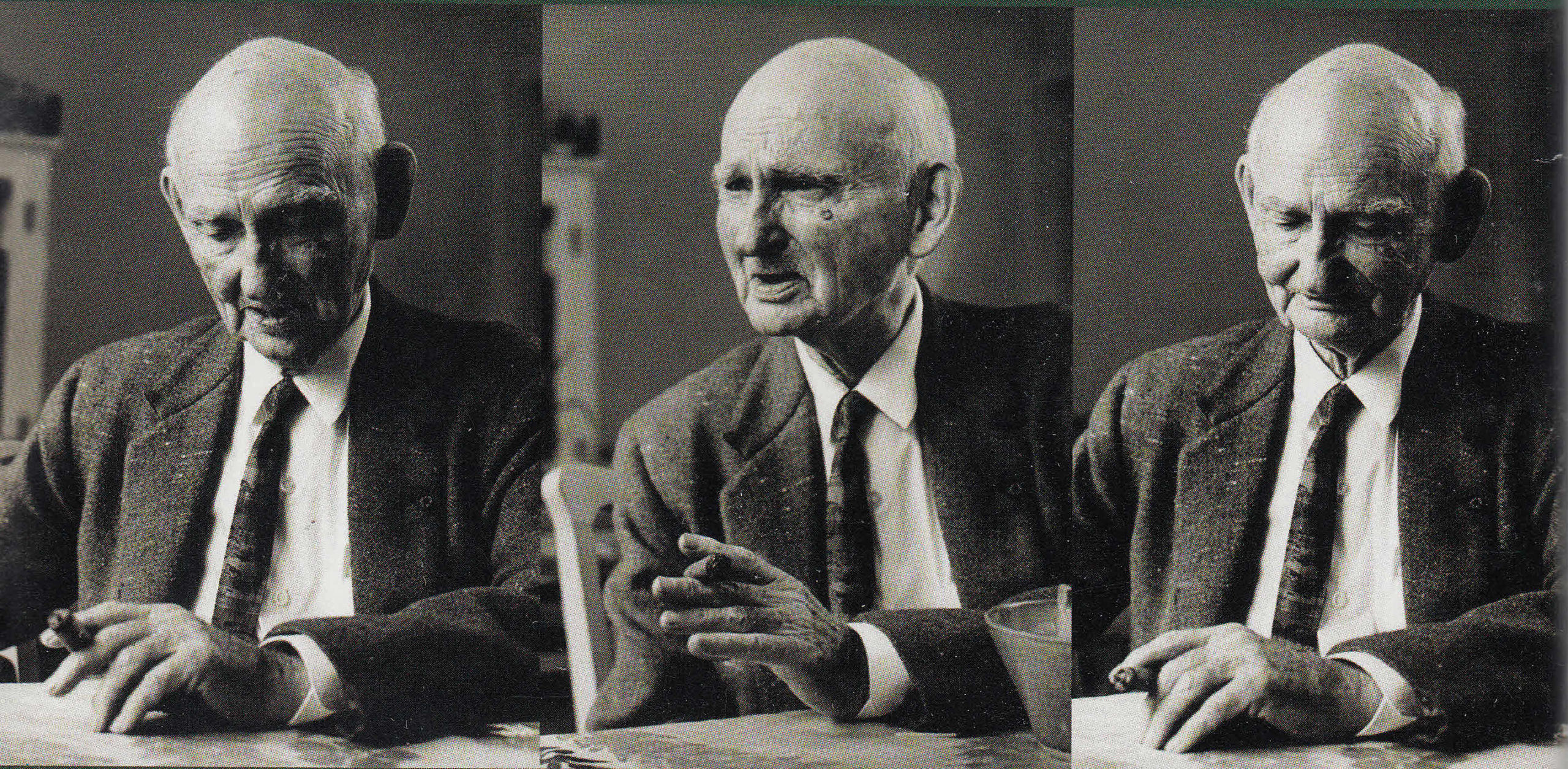

The first timpani stroke of the work hit the old man like a hammer. Suddenly he was sitting bolt upright, his eyes wild and open, like an eagle, his breath coming in fast, hoarse grunts and growls and guttered noise. ‘Fine.’ ‘Great.’ ‘Damn, DAMN FINE WORK!’ He kept it up right through the whole piece. Sometimes singing or moaning along with the music until the end. He turned toward me, sitting at his bedside and grabbed my hand in his, holding it in a viselike grip and just stared at me, saying nothing. We remained so awhile, then he settled back and began to talk, mostly about his friend [Charles] Ives (‘Charlie’), about [Edgard] Varèse, [the artist] Thomas Hart Benton. And music, music, music:

‘I don’t think much about that fellow Brahms. If you ask me, he’s just a big sissy – always hiding behind formal development resolutions, counterpoint – why doesn’t he just come out like a man and say what he means? And those titles of his – Capriccio Intermezzo – what the hell does that mean?

‘Debussy – a genius – nothing wrong with him that a few weeks in the open air wouldn’t cure.’

The word ‘fine’ was Mr. Ruggles’ ultimate superlative.

‘Oh, there are some fine works all right, the St. Matthew Passion, Missa Solemnis, The Ring, Tristan, and Sun-Treader. When I wrote Sun-Treader, I knew it was great. I knew it!

‘Bach, now there was a great melody writer – nobody appreciates that. Even the famous one like that, oh, you know, ‘Air’, [although] it can’t be played properly on the G string at all. Why, they just crap all over the thing, those goddamned violinists!’”

Okay then.

We might choose to write Ruggles’ remarks off as being those of a crabby, semi-senile old guy, although if we did, we’d have to call the 40-year-old Ruggles semi-senile as well, because that’s how he talked his entire life. He makes it all too easy for us to indulge in clichés, calling him a “New England Yankee”, a “maverick”, a “rugged individual” or, as Tilson-Thomas did at the beginning of his quote, “granitic.” Cliché or not, that is who Ruggles was: we hear it in his voice, and we certainly hear it in his music. This essentially self-taught composer, who slaved endlessly over his scores, whose total compositional output runs just 85 minutes in length, wrote some of the craggiest and most powerful music of the twentieth century.…

Continue reading, and see the prescribed recordings, only on Patreon!

Become a Patron!