What a birthday rip-off.

Until roughly March 15 of this year, I had always assumed that the two worst birthday rip-offs were being born on December 25 (“we’re giving you a combined birthday/holiday gift this year . . .”) and February 29 (“we’ll celebrate again in four years!”). But no, there is a bigger rip, and that’s having what should have been a yearlong celebration of concerts and colloquia and lectures and special events in honor of Beethoven’s 250th cut down to three months because of you-freaking-know-what.

Dang.

By the time we all start consistently crawling back to our concert halls – I’m thinking (hoping) winter-spring 2021, the Beethoven birthday year – which presumably runs from December 16, 2019 to December 16, 2020, will have come and gone.

HERE’S WHAT I PROPOSE, and pardon me for yelling. I propose we take a Mulligan, do the whole thing over, and extend the festivities by a full year. The Beethoven Symphonies, Concerti, String Quartets, Piano Sonatas, etc. and etc. that were scheduled for performances, only to be cancelled due to COVID-19, should simply be rescheduled. The activities and events surrounding the B-man’s B-day should, again, all be rescheduled. It’s only fair, and I’m not talking about fairness to Beethoven (because he’s dead and he doesn’t care) but to us, who are not dead and do care.

Are the people in power – the ones who can make this happen – listening to me?

THANK YOU. Thank you very much.

As charity starts at home, we here at Dr. Bob Prescribes will do our part and will continue the Beethoven celebration until 2021.

I’m feeling better now.

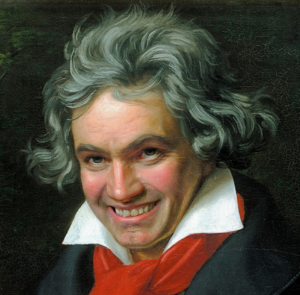

For various reasons, Ludwig van Beethoven (December 16, 1770- March 26, 1827) was never exactly sure about his age until his late thirties, when the legal battle over his nephew Carl forced him to accept the year of his birth as 1770.

A principal reason for his confusion was that throughout his childhood, Beethoven’s father, Johann van Beethoven, routinely lied about his son’s age in order to make his musical abilities appear to be that much more prodigious (as in “prodigy-like”). For example, when Beethoven made his first appearance as a pianist in the Rhineland city of Cologne (roughly 15 miles north of his hometown of Bonn) in 1778, he was billed as being a “six-year-old”. (Of this concert the venerable American musicologist Leon Plantinga – born 1935 – writes, “the concert was the opening salvo in Johann van Beethoven’s campaign to present the boy as a child prodigy,” a concert in which the young Beethoven played “various [unspecified] clavier concertos and trios.”)

The surviving manuscript of Beethoven’s Piano Concerto in E-flat, WoO 4 bears this inscription in Beethoven’s own hand on its title page: “un Concerto pour le Clavecin ou Fortepiano composé par Louis Van Beethoven agé douz ans” – “a concerto for harpsichord or piano composed by Louis van [small “v”!] Beethoven aged 12 years.” In fact, at the time of its composition – 1784 – Beethoven was actually approaching his 14th birthday.

Whether Beethoven was 12 or 13 years old when he composed the concerto is, in the end, immaterial. He was still a wee-shaver and the concerto is a solid piece of work, one not lacking in signposts pointing to his mature music. That Beethoven was capable of composing such a work at the age of 13 is due entirely to the instruction, support, and friendship he received from Christian Gottlob Neefe (pronounced “NAY-feh”; 1748-1798).

It is no overstatement to say that Neefe was not just Beethoven’s indispensible teacher but that single person who preserved Beethoven’s damaged psyche to the degree that he (Beethoven) was able (well, sort of able) to function in the real world as an adult.

Neefe settled in Bonn in 1779 at the age of 31 and was appointed principal organist for the Electoral Court on February 15, 1781. Sometime later that year he was entrusted with Beethoven’s musical apprenticeship. Neefe remained Beethoven’s principal teacher for eleven years, until Beethoven left Bonn for Vienna in late 1792.

According to Beethoven biographer Jan Swafford:

“Neefe’s enthusiasms were diffuse, likewise his creativity: he was a composer of sonatas, concertos, singspiels, and operas; writer of inspirational homilies, biographies, and autobiographies; critic and aesthetician of music; journalist; translator of libretti; and poet. Everything Neefe did was worthy and engaging, if a bit fearfully earnest. If nothing close to an original genius, he was one of the most interesting German creators of his time.”

This, then, is the man who gave Beethoven the opportunity to become Beethoven.

Neefe quickly recognized Beethoven’s genius and was unstinting in his praise and encouragement, something that fell like Hemp Emu on Beethoven’s frequently boxed ears (thanks, dad). Neefe taught Beethoven to play Bach’s magnificent organ works as well as the 48 preludes and fugues that together constitute Books One and Two of The Well-Tempered Clavier. Neefe oversaw Beethoven’s composing and taught him as well to conduct the court orchestra. Neefe also arranged to have some of Beethoven’s early compositions published and wrote an article in the third person about Beethoven that appeared in the Magazin der Musik on March 2, 1783:

“Louis van Beethoven is a boy of very promising talent. He plays the piano in a very finished manner and powerfully, reads at sight and plays the Well-Tempered Clavier of Sebastian Bach, which Herr Neefe put in his hands. Those who are familiar with this collection of Preludes and Fugues in every key – which one could practically call the ultimate in keyboard composition – will understand the significance of this. Herr Neefe has also given him instruction in harmony. Now he is teaching him composition and, in order to encourage him, has had published in Mannheim Nine Variations on a March. This young genius deserves a subsidy in order to enable him to travel. He will undoubtedly become a second Mozart if he continues to progress as well as he has begun.”

It was thanks to Neefe that Beethoven emerged from his shell during the second decade of his life. It was thanks to Neefe that in 1782 – at the age of eleven – Beethoven was appointed assistant court organist at the electoral court. (This was a huge step, and although it was not a salaried position, it lifted Beethoven out of the environment of his house and into that of the court. It boosted his self-esteem as both a person and as a musician immeasurably.)

I was thanks to Neefe’s instruction and support that on February 15, 1784, the now 13-year-old Beethoven applied for the job of deputy court organist there in Bonn; a fully salaried position. Almost certainly coached by Neefe, Beethoven, in applying for the position, the asked for an increase in the starting salary, stating bluntly that his drunken father was no longer capable of supporting his family. Four months later – on June 27, 1784 – Beethoven was appointed as Deputy Court Organist, an appointment that carried with it a salary of 150 florins. According to his neighbors, the Fischers:

“[Beethoven] now believed himself to be the equal of his father in music.”

In fact, by the age of 13 – thanks in large part to Neefe – Beethoven had already far outstripped his father as a musician.

The evidence for that statement is Beethoven’s Piano Concerto in E-flat major, composed at precisely the time he was appointed as Deputy Court Organist in mid-1784.

Reconstructions

Imagine if all we knew of Vincent van Gogh’s psychedelic masterpiece Starry Night was a black and white image?

Imagine if the only representations we had of the Palace at Versailles were exterior elevations, without a clue as to the interior spaces and design?

Such is the problem/challenge of Beethoven’s Piano Concerto in E-flat major, WoO 4. Neither the full score nor the individual instrumental parts have survived. All we have is the complete solo piano part, written out in an unknown hand, with the orchestral tuttis (that is, when the orchestra is playing by itself) written out as a “reduction”, as if it were also a piano part. While we know that Beethoven scored the concerto for a modest ensemble consisting of two flutes, two horns, and strings, we do not know how Beethoven actually orchestrated the tuttis. Neither do we do not know how the orchestra accompanied the piano part when the piano was in the “lead”, nor do we know what the orchestra was playing when it was in the lead and the piano was providing the accompaniment.

Consequently, like attempting to color in Starry Night or figure out the floor plan of the Palace of Versailles, any performance of Beethoven’s Piano Concerto in E-flat major, WoO 4 will be a reconstruction. … Continue reading, and see Dr. Bob’s Prescribed recording, only on Patreon!