Compositionally, 1806 was a miraculous year for Herr Ludwig van Beethoven. Among the works he completed that year were the Piano Sonata in F minor, the Appassionata, Op. 57; the Piano Concerto No. 4 in G major, Op. 58; the three so-called “Razumovsky” String Quartets, Op. 59, nos. 1, 2, and 3; the Symphony No. 4 in B-flat major, Op. 60; the Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 61; the second Version of his opera Leonore (as well as the Leonore Overtures nos. 2 and 3) (Leonore was renamed Fidelio in 1814); 32 Variations on an Original Theme in C minor, WoO (without opus) 80; and Six Ecossaises for piano, WoO 83;

(For those who’s like to know much more about Beethoven in 1806, I can happily recommend Mark Ferraguto’s excellent Beethoven 1806, published by Oxford University Press in 2019.)

Crazy. Some ten years into his hearing loss, in poor mental health, and plagued by gastric issues that would lay most of us low for weeks at a time, Beethoven’s creative juices and sheer ingenuity were running at a level inconceivable to any of us today.

His Violin Concerto received its premiere that same year – 1806 – on December 23. Legend has it that the concerto was completed just two days before the premiere and that the concerto’s dedicatee, the violinist Franz Clement, had to sight-read the third movement finale at the concert. …

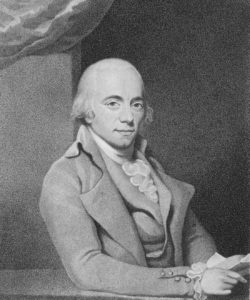

We owe the existence of the piano version of Beethoven’s violin concerto to the Italian composer, pianist, teacher, piano manufacturer, and music publisher Muzio Clementi (1752-1832), he of the “Six Sonatinas for Piano” fame. (For those of you unfamiliar with the Sonatinas Op. 36, they are utterly ubiquitous in the pedagogic literature: everyone, and I mean everyone who is two or three years into piano lessons will have played, at least, the Sonatina No. 1 in C major.)

Muzio Filippo Vincenzo Francesco Saverio Clementi was born in Rome on January 24, 1752, making him almost exactly four years older than Mozart. The eldest of seven children, his prodigious musical talent revealed itself early on, and by the age of 13 he was composing and playing keyboard instruments professionally.

In 1766, at the age of 14, a wealthy Englishman named Sir Peter Beckford heard Clementi play the organ in Rome and was knocked out by his talent. Beckford hired him on the spot, and after negotiations with Clementi’s father, took the boy home with him to his estate in Dorset, England. For the next seven years Clementi lived, performed, and studied at Beckford’s estate in Dorset, during which time he practiced the harpsichord eight hours a day, every day. In 1774 – at the age of 22 – Clementi moved to London and began concertizing as an organist, harpsichordist, and pianist.

In 1780, the 28 year-old Clementi began what turned out to be a three-year musical tour of the continent. He started in Paris where he performed for none-other-than Queen Marie Antoinette, the sister of Emperor Joseph II of Austria. He slowly worked his way across Europe, arriving in Vienna in December of 1781, where he agreed to participate in a musical contest with the local light – the former child prodigy Wolfgang Mozart – for the entertainment of Emperor Joseph II and his guests on Christmas Eve of 1781.

It’s a great story, one I will tell in detail at an appropriate time. For now, let us observe that back and forth Mozart and Clementi went, improvising, playing sonatas of their own composition, and sight-reading near-illegible manuscripts by other composers. …

In 1783 Clementi headed back to London, there to earn many a Kreutzer as a pianist, composer, piano builder and finally, as a publisher. It was in his capacity as a major English music publisher that he visited Beethoven in 1807. His timing could not have been better, as Beethoven was looking for an English publisher. (In those days, publishing rights were, unless otherwise specified, territorial: the same piece could be published by different companies in London, Paris, and Vienna providing that those publishers sold within their territories. This, however, did not preclude Beethoven from selling “exclusive” publication rights to multiple publishers within the same territory. Dirty business, that.)

Writing in English to his partner back in London, Clementi described his “courtship” of Beethoven.

“I have at last made a complete conquest of that haughty beauty Beethoven, who first began at public places to grin at me. Which of course I took care not to discourage; then slid into familiar chat, until meeting him by chance one day in the street.

‘Where do you lodge?’ says he, “I have not seen you this long while!’ – upon which I give him my address.

Two days after, I find on my table his card, brought by himself, from the maid’s description of his lovely form. This will do, thought I.

Three days after that, he calls again and finds me at home. Conceive, then, the mutual ecstasy of such a meeting! I took pretty good care to improve it to our house’s advantage. In short, I agreed with him to take in manuscript three [string] quartets [the Razumovskys], a symphony [the Fourth], an overture [the Coriolan], a concerto for violin which is beautiful and which, at my request, he will adapt for the pianoforte, and a concerto for the pianoforte [the Fourth], for all of which we are to pay him one hundred pounds sterling [$11,104.04 at the time of this writing, July 12, 2020]. I think I have made a very good bargain. What do you think?”

Yes, we think Clementi made a very good bargain indeed. He would have made that money back within days of publishing those works, after which everything would have been profit.

Beethoven immediately got to work on the piano arrangement of the violin concerto. The arrangement was published in 1807, a full year before the original violin version, which didn’t appear in print until 1808.…

See the full post, and see the prescribed recording, only on Patreon!