A composer’s most prized possessions are his/her autograph manuscripts: complete scores notated in pencil or ink. (We pause to rue the passing of such hand-written manuscripts. As a new generation of composers notates music using computer programs, the art of music calligraphy will go the way of the hand-copied illuminated manuscript, and technology will claim another victory over an ancient craft. But worse, we – as students and lovers of music – will lose an irreplaceable resource: hand-copied manuscripts, from which we can learn an amazing amount about composers, their music, their personalities, and their creative processes. In the same way a graphologist – a handwriting analyst – “reads” someone’s handwriting for insights into his personality, so we can “read” a music manuscript for insights into a composer and the piece itself. Absent such manuscripts, we will be so much the poorer.)

A composer’s most prized possessions are his/her autograph manuscripts: complete scores notated in pencil or ink. (We pause to rue the passing of such hand-written manuscripts. As a new generation of composers notates music using computer programs, the art of music calligraphy will go the way of the hand-copied illuminated manuscript, and technology will claim another victory over an ancient craft. But worse, we – as students and lovers of music – will lose an irreplaceable resource: hand-copied manuscripts, from which we can learn an amazing amount about composers, their music, their personalities, and their creative processes. In the same way a graphologist – a handwriting analyst – “reads” someone’s handwriting for insights into his personality, so we can “read” a music manuscript for insights into a composer and the piece itself. Absent such manuscripts, we will be so much the poorer.)

Autograph manuscripts are unique in that there is only one “final, autograph manuscript” of any given piece. In the days before photocopy machines, composers guarded their unpublished manuscripts with maternal ferocity, storing them in safes and vaults.

Because of everything it embodies, the greatest gift a composer can bestow is the gift of a manuscript. A composer will do so to honor a dedicatee or as a gesture of thanks to a patron. The one thing a composer requires in return is the assurance that the manuscript will be kept in a cool, dry, safe place. Wealthy people tend to have more such places than composers. Wealthy people are also more likely to finance future projects if their largesse is rewarded with a manuscript or two.

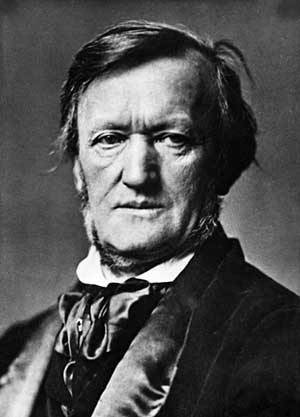

For these reasons Richard Wagner made an extraordinary gift of manuscripts to his patron, King Ludwig II of Bavaria, on the occasion of the king’s twentieth birthday on August 25, 1865. The gift included Wagner’s handwritten manuscript scores of his first three operas – The Fairies, The Ban on Love, and Rienzi – as well as the manuscript scores of The Rhinegold, The Valkyrie, and orchestral sketches of Siegfried.

After Ludwig’s death, Wagner’s manuscripts remained in the hands of his heirs, the Wittelsbach family. On April 18, 1939, the manuscripts were purchased by the German Chamber of Industry and Commerce for 800,000 marks (roughly $200,000). Two days later, on April 20, 1939, the manuscripts were presented to Adolf Hitler as a gift in honor of his fiftieth birthday. Hitler adored Wagner, and was famously quoted as having said:

“Whoever wants to understand National Socialistic Germany must know Wagner.”

Hitler kept the manuscripts in the Reich Chancellery, which was at the corner of Ebertstrasse and Voss Strasse in Berlin. With the war approaching its end, Hitler moved them into his bunker under the Chancellery. There they remained as he and his Reich – like Valhalla itself – went up in flames. Wagner’s manuscripts were never found. They may have been burned along with Hitler and his other papers. Maybe they’re sitting in a warehouse somewhere in Eastern Europe, among the 180,000-plus pieces of German art still missing and claimed by experts to be hidden in secret depots in the former Soviet Bloc. Perhaps they’re rotting in an attic somewhere in the former Soviet Union, forgotten war-booty; or sitting in the air-conditioned vault of a wealthy and anonymous collector. Perhaps they’ll turn up one day; or perhaps they won’t.

This post was excerpted adapted from my Great Courses survey, “The Music of Richard Wagner.” In the spirit of appropriate self-promotion, I would invite any and all interested to consider investing in what I consider to be an honest [if hard-hitting] course on Wagner and his utterly unique body of work.

Beautiful post. You will be glad to know, Prof. Greenberg, that on my girlfriends last birthday I gifted her a handwritten manuscript of a short prelude I had written for her. I wrote it, nervously, in ink and even went so far as to write the lines of the staff myself. She loved the gift, which alone was satisfaction enough, but I also found immense pleasure in creating it by hand. I love the act of putting pen to paper and carry with me everywhere a rather large book, aptly named “The Big Book of Staff Paper”, to jot down my musical ideals. Don’t worry, there are a still a few of us youngsters who enjoy the “ancient craft”!

Wonderful, and thanks for the comment!