We mark the premiere performance on August 28, 1850 – 173 years ago today – of Richard Wagner’s opera Lohengrin, in the central German city of Weimar.

The premiere was conducted by none-other-than Wagner’s friend and supporter (and future father-in-law!) Franz Liszt (1811-1886). Liszt had chosen the premiere date of August 28 in honor of Weimar’s most famous citizen, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, who was born on August 28, 1749, 101 years to the day before Lohengrin’s premiere.

The “opera” – the last of Wagner’s stage works to be designated by him as being an “opera” – was brilliantly received and has been a mainstay of the international repertoire since that first performance.

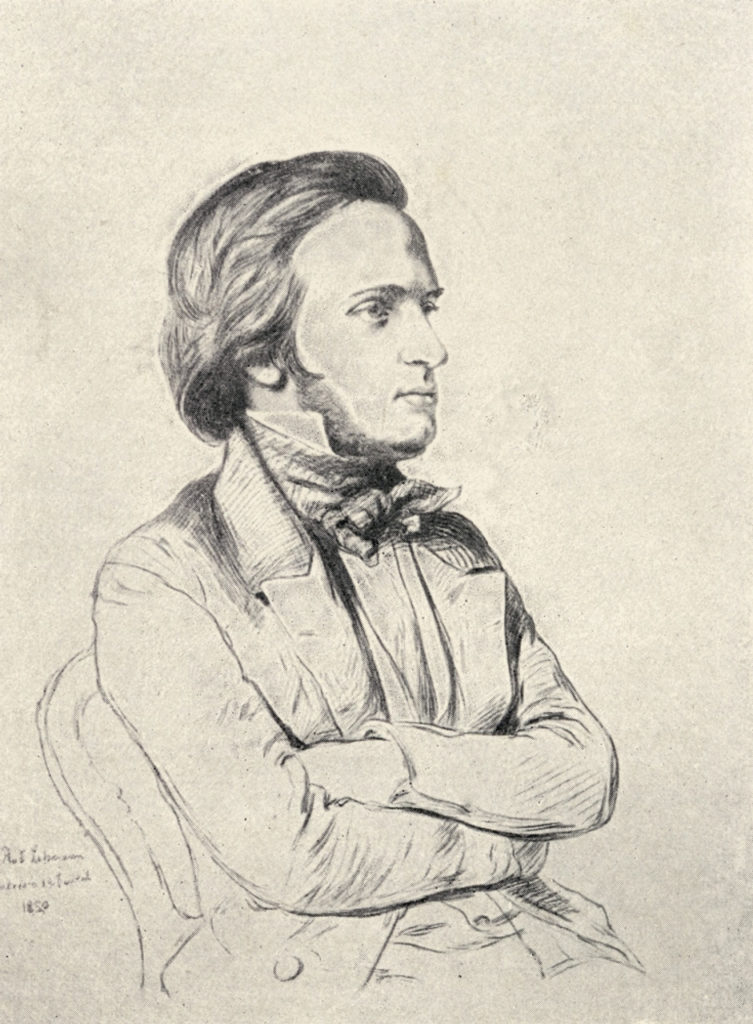

Alas, Richard Wagner (1813-1883) was not in attendance there at the premiere. With a price on his head, he had been de-facto exiled from Germany thanks to his activities in the Dresden Uprising of May of 1849. Wagner did not hear a full performance of Lohengrin until 1861, 11 years later, in Vienna.

Be informed that both today’s Music History Monday and tomorrow’s Dr. Bob Prescribes posts will deal with Lohengrin. Tomorrow’s Dr. Bob Prescribes will focus on three video performances, comparing video excerpts from each of the three performances in our search for a single, prescribed recording.

Wagner in Dresden and the “Education” of an Audience

Wagner was hired as Assistant Kapellmeister of the Royal Dresden Opera in 1843, at the age of 30. From the moment he took the job, his burning ambition was to turn Dresden into a hot bed for new German opera. In order to do that, he had to convince the conservative Dresden opera audience to embrace and support opera that was new and different.

A tall order that, “educating the audience,” one that long experience tells us only rarely succeeds. But we’re talking here about the human dynamo that was Richard Wagner, for whom, in Dresden at least, “failure” was not an option.

More than anything else, it was Wagner’s own operas that converted a significant portion of his Dresden audience from the “staid” to the “adventurous.” Wagner’s opera Rienzi – a traditional pot-boiler written in the contemporary French-style – won the Dresden audience over to Wagner almost immediately in October of 1842. The Flying Dutchman – premiered in Dresden on January 2, 1843 – was another thing altogether. A psychodrama with terrifically challenging vocal parts, it left its audiences confused: not particularly “entertained”, but not turned off, either. Having said that, the fact that The Flying Dutchman turned out to be a huge hit in other German cities instilled no small bit of pride in the Dresden musical community, which, for the most part, came to be delighted with its assistant Kapellmeister.

The response to the premiere of Wagner’s Tannhäuser on October 19, 1845, made it clear that something special was happening in Dresden. In an article that appeared in the Leipzig journal “Signal for The Musical World,” the Dresden correspondent wrote:

“It is a noteworthy phenomenon that the cool and unexcitable Dresden theater public has been transformed by Wagner’s operas into a fiery and enthusiastic body such as can be found nowhere else in Germany.”

That “fiery enthusiasm” for Wagner’s operas soon spread across all of what today is Germany. It wasn’t just that Wagner was a German composer writing German language operas based on Germanic-slash-Nordic subject matter. Even more, it was because Wagner’s music was evolving away from traditional Italian and French operatic practice, towards something of his own making. In Tannhäuser, Wagner blurs the edge between recitative and aria: between action music and lyric music. This was something new for German audiences, and it allowed dramatic momentum to build more powerfully, unchecked by “traditional” structural divisions. Wagner also deployed his pit orchestras ever more symphonically, with the result being a level of instrumental magnificence that drove German audiences wild, even though it sometimes drowned out smaller-voiced singers who could not compete with the orchestra on equal terms. (When we call someone a “Wagner singer,” what we’re saying is that a singer has a voice “big enough” to be heard over a “Wagner orchestra!”)…

Continue Reading, and listen without interruption, only on Patreon!

Become a Patron!Listen and Subscribe to the Music History Monday Podcast

Podcast: Play in new window

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Pandora | iHeartRadio | RSS | More