It was on August 24, 1975 – 45 years ago today – that Queen began recording Bohemian Rhapsody at Rockfield Studio No. 1 in Monmouth, Wales. It would take a total of three weeks to record the song. We are told that Freddie Mercury had “mentally prepared the song beforehand” and thus he directed the sessions. We are also told that Mercury, along with fellow bandmembers Brian May and Roger Taylor, sang their vocal parts pretty much non-stop for “ten to twelve hours a day”, resulting, in the end, in 180-plus separate overdubs (to say nothing for sore throats and hoarse voices!).

I Confess

I have been accused of being a critical Pollyanna, of heaping praise on every work and performance I write about; of employing such adjectives as “brilliant”, and “amazing”, and “outstanding”, and “singular”, and “awesome”, and “astonishing”, and “extraordinary” to a frankly tiresome degree.

To such accusations I stand guilty as charged.

Here’s the thing (or “things”, as the case may be). First, my formal training is in music composition, not musicology. I am not, nor have I ever claimed to be, a “musicologist” (though I am occasionally billed as such by good people who do not know any better). What that means is that I have no emotional or professional stake in any particular slice of the repertoire; and thus I have no need to degrade one chunk of repertoire or genre of music in order to elevate another (please, don’t even think of getting me started on this!). Second, I am not (and never will be) a “critic”, someone who feels that he or she is uniquely suited, somehow, to judge their betters and in doing so address what they, in their heightened wisdom, consider to be the good, bad, and ugly of the artistic world.

(We would generously observe that critics are just people; people with their own closeted skeletons, prejudices, and egos; people who for the most part never managed to become the composers and performers they would profess to criticize.)

What all of this comes down to is that I appear to be a critical Pollyanna because I only write about music and performances I care about. Conversely, I do not write about composers who, for whatever reasons, I do not like or respect (for example, the contemporary composer who shares his name with the second President of the United States), or performers who make the music they perform all about themselves (see the following sentence). Besides, a negative comment from me about Bang-Bang, for example, will only serve to upset those who enjoy his piano playing and contribute nothing to the greater musical good. Consequently, I will write about what I find exciting, beautiful, and inspirational and will leave the rest to others.

Except today.

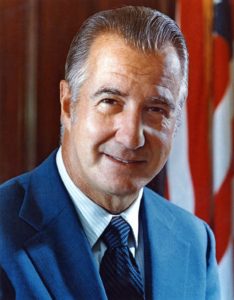

Yes, today your ordinarily sunny and quick to praise Dr. B. will become, here, a nattering nabob of negativism (thank you, Spiro T. Agnew, for that phrase), as the circumstances of today’s date force us to examine what is, without any doubt, the most overrated, over-praised, over-analyzed rock ‘n’ roll song ever, Freddy Mercury’s Bohemian Rhapsody.

A request: go listen to this train wreck of a song and then return to this post; here’s a link to the “Official Remastered Video” of Bohemian Rhapsody:

Why do I hold this song in such low regard, its insipid music and lyrics (which make John Lennon’s 1967 I Am the Walrus sound like the most transparent Haiku by comparison) in such low regard?

I will gladly admit that my low regard for Bohemian Rhapsody is in inverse proportion to the ecstatic critical acclaim with which the song is now regarded by that strangest of critical animals, the so-called “rock critic”, who routinely seek to justify their questionable career choice by attempting to identify multi-layered complexity and metaphor in music that is often nothing but thin-layered crud.

Let us begin by identifying what Bohemian Rhapsody is, what the band – Queen – thought of it while recording it, and then we’ll observe the critical acclaim that has since accumulated around it like bull patties in a stockyard.

The song, which runs an excruciating five minutes and fifty-five seconds in length, is actually three songs strung loosely together (in 1985, Mercury said, “it was basically three songs that I wanted to put out and I just put the three together”).

The first of these songs is a ballad preceded by an a cappella introduction, during which the singer – Mercury – informs his mother that he has been a naughty, naughty boy, explaining:

“Mama, just killed a man Put a gun against his head Pulled my trigger, now he's dead.”

[Yes, funny how that happens.]

Okay; that’s a strange subject for a “ballad”, but let’s keep going.

The second section – the second “song” of Bohemian Rhapsody – is the so-called “opera section.” The producer Roy Thomas Baker recalled when Mercury first played the opening ballad section for him on the piano:

“He played the beginning on the piano, then stopped and said, ‘And this is where the opera section comes in!’ Then we went out to eat dinner.”

Of course, that second section is not opera at all, but a rather sophomoric parody thereof, a bit of nonsense based on a handful of such Italian-sounding words as Scaramouche, fandango, Galileo Galilei, and Figaro. (The story has it that Mercury had written “Galileo” into the lyrics in honor of his bandmate Brian May, born 1947, whose passionate interest in astronomy led to his receiving a Ph.D. in astrophysics from London’s Imperial College on May 14, 2008.)

The third and final section (or song) is a hard rock number, followed by a quiet coda that concludes cryptically with the Forrest Gump-like epigram “any way the wind blows.”

Back, for a moment, to John Lennon’s I am the Walrus (koo-koo-ka-chu). Lennon’s lyrics have been the subject of endless literary interpretations, scholarly analyses, and even dissertations.

“Yellow matter custard Dripping from a dead dog's eye Crabalocker fishwife, pornographic priestess Boy, you've been a naughty girl, you let your knickers down.”

Quite a lyric. As it turned out, John Lennon later admitted to having written the lyrics of I Am the Walrus in order to purposely confuse those many people who were subjecting the Beatles’ songs to serious, scholarly analysis. Got it? The words to I Am the Walrus are purposely nonsensical! Which has not stopped a single academe or rock critic from analyzing them as if there were the utterances of Moses from Mt. Sinai. For example, writing in 2014 in the journal “Procedia: Social and Behavioral Sciences”, Artyom S. Zhilyakov asserts that:

“The analysis of the local language picture of the world in the lyrics of The Beatles’ I Am the Walrus seriously exceeds the overall linguistic background, it provides an opportunity to reflect on the nature of the creative process. The linguistic and literary discourses found [in I Am the Walrus] during cognitive immersion tend to mark the process of intercultural communication.”

Right. Un-huh.

Back to Bohemian Rhapsody.

According to Freddie Mercury’s friend, the DJ and television personality Kenny Everett (who played a key role in promoting Bohemian Rhapsody on his radio show on Capital Radio, the lyrics have no meaning whatsoever; that Mercury told him that the words were simply “random rhyming nonsense”.

Bohemian Rhapsody’s producer Roy Thomas Baker recalled in 1999:

“Bohemian Rhapsody was totally insane, but we enjoyed every minute of it. It was basically a joke, but a successful joke. [Laughs]. We had to record it in three separate units. We did the whole beginning bit, then the whole middle bit and then the whole end. It was complete madness. The middle part started off being just a couple of seconds, but Freddie kept coming in with more “Galileos” and we kept on adding to the opera section, and it just got bigger and bigger. We never stopped laughing.”

Baker further observed that:

“Every time Freddie came up with another ‘Galileo’, I would add another piece of tape to the reel.”

“We never stopped laughing.”

And well they might still be laughing, because the whole Bohemian Rhapsody trip was indeed a lark, in the words of its producer, “basically a joke” (whether a good joke or a bad one we leave up to the ears of the individual listener). Being declared a “joke” by its creators and producer has not precluded the listening public and the critical community from turning Bohemian Rhapsody into a musical cause celebre, a defining masterwork, a philosophical tract of generation import, among the greatest rock ‘n’ roll songs of all time. (It routinely polls in the top five of “greatest songs of all time” and in 2012, the readers of Rolling Stone chose Mercury’s performance “as the greatest in rock history.”)

Okay; we get that for whatever reasons, the song is “popular”. But it’s the scholarly appraisals that leave me shaking my head.

According to the English musicologist Sheila Whiteley writing in her book Queering the Popular Pitch (Routledge, 2006):

“The title [Bohemian Rhapsody] draws strongly on contemporary rock ideology, the individualism of the Bohemian artists’ world, with rhapsody affirming the romantic ideals of art rock.”

(Whitely also asserts that the opening ballad, during which the narrator confesses murder to his mother, is “affirmative of the nurturant and life-giving force of the feminine and the need for absolution.”)

Despite Mercury’s admission that the song’s lyrics are nonsense, critics continue to insist on interpreting them as if they are not. Some claim that the lyrics are autobiographical; others assert – without any evidence – that they were inspired by Albert Camus’ novel The Stranger, a story about a young murderer; others claim that the lyrics are about Mercury’s “coming out” as a homosexual:

“Living with Mary (‘Momma’, as in Mother Mary) and wanting to break away (‘Momma Mia let me go’)”.

In 2009, Tom Service, the music critic for The Guardian, attempted to place Bohemian Rhapsody within the context of nineteenth-century concert music:

“The precedents of Bohemian Rhapsody are as much in the 19th-century classical traditions of rhapsodic, quasi-improvisational reveries—like, say, the piano works of Schumann or Chopin or the tone-poems of Strauss and Liszt as they are in progressive rock or the contemporary pop of 1975. That’s because the song manages a sleight of musical hand that only a handful of real master-musicians have managed: the illusion that its huge variety of styles—from intro, to ballad, to operatic excess, to hard-rock, to reflective coda—are unified into a single statement, a drama that somehow makes sense. It’s a classic example of the unity in diversity that high-minded musical commentators have heard in the symphonies of Beethoven or the operas of Mozart. And that’s exactly what the piece is: a miniature operatic-rhapsodic-symphonic-tone-poem.”

Oh PLEASE; there are so many things wrong with that paragraph that it would take an entire blog post to enumerate them. Suffice it for now that Service’s comment is a text-book example of what happens when an over-earnest critic attempts to validate something by creating a series of utterly inappropriate comparisons and false parallels.

And there it is, the intellectual trap faced by the so-called “rock critic”: it’s what happens when a literate, knowledgeable critic must write about works created by often semi-literate rockers, one artistic step above teenaged garage bands. The issue isn’t one of elitism, it’s about finding appropriate language to address the music. I adore folk art and found art, for example, but I do not believe it is relevant to address that art with a vocabulary created for Michelangelo, Titian, Caravaggio, Vermeer, Rembrandt, Raphael, Renoir, van Gogh and Picasso.

In the end, what does all the highfalutin’ verbiage written about Bohemian Rhapsody tell us? It tells us how easily fooled we can be when searching for high artistic substance in something that, in reality, has little artistic substance at all.

Rock ‘n’ roll critics would be advised to tread cautiously.

Galileo, Galileo, Galileo.

Listen on the Music History Monday Podcast

Podcast: Play in new window

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Pandora | iHeartRadio | RSS | More

Become a Patron!