We would note two major events on this day from the world of opera. We will mark the first event in a moment; the second event – which constitutes the body and soul of this post – will be observed only after we’ve had a chance to do some prep.

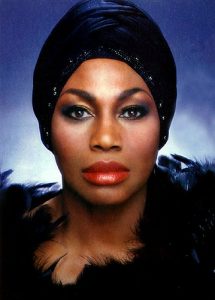

We mark the birth on February 10, 1927 – 93 years ago today – of the glorious soprano Leontyne Price. (More than just a soprano, Price in her prime was a lyric-spinta, or “pushed lyric soprano”, meaning that she had all the high notes of a lyric soprano but could also push her voice to realize dramatic climaxes without any strain. The great lyric-spinta roles include Aida, Desdemona from Verdi’s Otello, the Marschallin from Richard Strauss Der Rosenkavalier, and Floria Tosca.) Every inch the true diva (in the best sense), Price is alive and we trust well at her home in Columbia, Maryland. Happy birthday, you stunning goddess you.

Preliminaries

A “malaprop” (or “malapropism”) “is the use of an incorrect word in place of a word with a similar sound, resulting in a nonsensical, sometimes humorous utterance.”

“Gibberish” (a.k.a. jibber-jabber or gobbledygook) is a tad different; it is defined as being “nonsense speech that may include speech sounds that are not actual words, or language games and specialized jargon that seems nonsensical to outsiders.”

I would suggest that the greatest English language-speaking master of both malaprops and gibberish was the baseball catcher, coach, manager, and Hall-of-Famer Lawrence Peter “Yogi” Berra (1925-2015). Malaprops and gibberish poured forth from his 5’7” frame like that proverbial poop from a goose; that they were uttered inadvertently make them all the funnier.

Should we want to (and I will admit that I am tempted), the remainder of this post could consist entirely of what have come to be known as “Yogi-isms.” Among the untold number of malaprops he uttered over his 90 years of life are such gems as:

“It ain’t the heat; it’s the humility.”

“I take that with a grin of salt.”

“Texas has a lot of electrical votes.” (As opposed to “electoral” votes.)

But truly, Berra’s greatest verbal creations are his gibberish: nonsense sentences, some of which have actually become part of our everyday lexicon. Bartlett’s Familiar Quotations features eight such Yogi-isms. A quick sampling must include such gems as:

“When you come to a fork in the road, take it.”

“You can observe a lot by just watching.”

“It’s like déjà vu all over again.”

“It’s tough to make predictions, especially about the future.”

“No one goes there nowadays, it’s too crowded.”

“Baseball is 90% mental and the other half is physical.”

“Always go to other people’s funerals, otherwise they won’t come to yours.”

“If you don’t know where you’re going, you might wind up someplace else.”

And finally,

“Never answer an anonymous letter.”

Thank you, Maestro Berra; these are wonderful; just wonderful.

Such was Yogi Berra’s reputation that every now and then he was credited with having said something he never in fact said. Perhaps the most famous such misattribution (aside from “anyone who goes to a psychiatrist should have his head examined”, which was, in fact, articulated by the movie mogul Samuel Goldwyn) is:

“It ain’t over until the fat lady sings.”

(Yes, Yogi Berra did indeed coin the phrase “it ain’t over till it’s over”, but there was no rotund, obese, zaftig, corpulent or Rubenesque lady in his utterance.)

“It ain’t over until the fat lady sings.”

No one is exactly sure where the phrase came from, although today it does tend to be used – when it is used at all – to state that anything is still possible during the course of a sporting event.

Having said that, it appears likely that the phrase was minted in response to Richard Wagner’s massive, four-evening, 17-hour long Ring Cycle, Der Ring des Nibelungen (“The Ring of the Nibelung”). The cycle consists of four music dramas; in order: Das Rheingold (“The Rhine Gold”), Die Walküre (“The Valkyrie”), Siegfried, and Götterdämmerung (“Twilight of the Gods”).

In the end, the “star” of the Ring Cycle is the Valkyrie Brünnhilde, who single-handedly brings about the destruction of the old, corrupt world of the gods and heralds in the dawn of the age of man. (“Age of person”? How might we make “age of man” gender-neutral?). The role of Brünnhilde is one of the most difficult soprano roles in the entire repertoire; the singer must have the stamina of an ultra-triathlete and the power of a super-heavy weightlifter. That sort of stamina and power typically requires a thorax the size of a Volkswagen bus, and a woman with a thorax that size will typically appear to be packing some significant heft. While it might be unkind to call such a woman a “fat lady”, it is not – from an observer’s point of view – particularly inaccurate.

The final 20 minutes of Götterdämmerung, and therefore the final twenty minutes of the entire 17-hour Ring Cycle, consists of a huge “aria” sung by Brünnhilde. And there it is: “it (meaning the Ring Cycle) ain’t over until the fat lady sings.”

A reminder: the title of this post is “It Ain’t Over Until the Fat Man Sings!”

Luciano Pavarotti

On February 10, 2006 – 14 years ago today – Luciano Pavarotti concluded the opening ceremony of the XX Winter Olympic Games in Turin, Italy by singing his trademark aria “Nessun Dorma” (“No one sleeps”) from Puccini’s opera Turandot. His performance was the hit of the show and received – by far – the longest and loudest ovation of the evening.

It was a long, crazy-complex show. Aside from the traditional march of the athletes (“The Parade of Nations”) and lighting of the Olympic flame, the ceremony consisted of thirteen separate acts, each with its own theme, music, and choreography. 6340 performers were involved. The central theme of the show was Italy itself; the ceremony was an unabashed celebration of things Italian; the official “Patroness (Mistress) of Ceremonies” was none other than Sophia Loren. Some 35,000 people were there at the Stadio Olimpico in Turin to witness the show live, an audience that included numerous heads-of-state and hundreds (if not thousands) of international celebrities. 32 cameras were involved in the live television broadcast, which was watched by an estimated two-billion people worldwide.

The thirteenth and final act of the ceremony was entitled “Fortissimo: Allegro with Fire”; it ran seven minutes in length. It began with the largest curtain ever constructed to that time opening on the 4000 square-meter/43,056 square-foot stage to reveal a full orchestra and Luciano Pavarotti who, as you have already deduced, is the “fat man” of this post’s title. (Please, THERE’S NO FAT SHAMING GOING ON HERE, we’re just dealing in facts. Pavarotti loved his food. He stood 5’11” tall, and at his heaviest – in 1978 – he topped out at 396 pounds. Like many of us, yours truly included, he struggled with his weight for most of his adult life. Sadly, for him, the weight won, and his health suffered significantly. Our hearts go out to him, but none of this changes the fact that he fit to a “T” the stereotype of the rotund opera singer.)

Pavarotti – dressed in a tuxedo with a black cape embroidered with silver Olympic rings – brought the opening ceremony to its conclusion with his rendition of “Nessun Dorma,” which itself concludes with three repetitions of the word vincerò, meaning “I will win!” It was an awesome and awe-inspiring performance; the audience hooted and hollered and stomped their feet, prompting NBC’s broadcaster Brian Williams to remark:

“And the master brings the house down.”

And thus the opening ceremony was over when the fat man sang.

Sadly, it wasn’t the only thing that was over because, as it turned out, the ceremony was to be Pavarotti’s last public performance. Five months later, in July of 2006, while in the midst of planning what would have been his “farewell (or retirement) tour”, the 70-year-old Pavarotti was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. He fought hard and long, but the cancer took him at his home in Modena on September 6, 2007, five weeks short of his 72nd birthday.

An Ironic Postscript

For all its glitz and hoopla and visibility, Pavarotti had no desire to perform at the opening ceremony of the Turin games. According to Pavarotti’s manager Terri Robson, the singer had repeatedly turned down invitations from the Winter Olympic Committee to sing at the ceremony. His reasons? Along with his health issues (or perhaps because of his health issues), he had no intention of singing outdoors, at night, in Turin’s frigid, mid-winter weather.

In the end, the Winter Olympic Committee persuaded Pavarotti to participate by allowing him to pre-record the aria and lip-synch the performance, about which no one was the wiser until 2008. That’s when the conductor at the ceremony, Leone Magiera, spilled the beans in his memoirs titled Pavarotti Visto da Vicino, in which he confessed that the entire performance – orchestra and voice – had been recorded in a nice, toasty studio weeks before. Magiera wrote:

“The orchestra pretended to play for the audience, I pretended to conduct, and Luciano pretended to sing. The effect was wonderful.”

Wonderful? Not so wonderful, we think. And there’s the irony: that the magnificent Luciano Pavarotti’s “final performance” was as a mime, and not as a singer.

For lots more on the foibles of singers and the world of opera in general, I would humbly direct you to my Great Courses/Teaching Company survey How to Listen to and Understand Great Opera, and to follow me on Patreon.

Listen on the Music History Monday Podcast

Podcast: Play in new window

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Pandora | iHeartRadio | RSS | More