On April 29, 1798 – 221 years ago today – Joseph Haydn’s oratorio The Creation was first performed before a star-studded, invitation-only audience at the Schwarzenberg Palace in Vienna.

Getting older, or “when I’m 65.”

An ugly confession. Eleven days ago, on April 18, 2019, I turned 65 years old. Don’t get me wrong; I am aware that growing older is generally preferable – generally – to the alternative. But it is, nevertheless, an ongoing shock to the system. Like many of us, I fully intended to be Peter Pan (Bob Panberg?): the eternal boy. And while one may not inaccurately assert that that is a fair appraisal of my emotional age, it cannot be said of my physical age. My eyes continue to weaken. My joints – crapped up by years in the gym – remind me of their ever-greater unhappiness by making ever more noise. My ability to dredge up names has become increasingly more difficult (although, curiously, dates and numbers come to me instantly). As my hairline beats an increasingly hasty retreat, thick, disgusting fly hairs on my shoulders and back continue to grow in ever greater profusion (this is so gross I don’t know where to start).

My father, who lived to 92, liked to say that age was “only a numbah”, even as – like Jeff Goldblum in the movie The Fly – he’d put one piece after another of his body into his medicine cabinet for safekeeping.

My “baby” brother the radiologist, who is only 63, has observed that “you’re only as old as you smell,” a claim that has given me cause for hope as I haven’t taken on that sickly-dry smell of desiccation, at least not yet.

Having said all of this, there is someone who has given me true hope, solace, and perspective in this whole aging thing, and that person is none-other-than the awesome/magnificent Oprah Winfrey. Oprah and I were born in the same year: 1954 (although she is some 10 weeks older than I am, har-har!). When Oprah has a landmark birthday she tends to make some wonderful, optimistic statement that, 10 weeks later, applies to me as well. Accordingly, in 2004 Ms. Winfrey announced that “50 is the new 30”; in 2014 she told us that “60 is the new 40.” And while she hasn’t commented yet on 65, I’m hoping for something on the lines of “65 is the new 14” which will, at least, square me with my emotional age.

If Oprah Winfrey is correct – and given the state of modern medicine, nutrition, hygiene, relatively clean water and air, etc. “60 might very well be the new 40” – then for Joseph Haydn, living in 1798, his 66 years would be the equivalent, today, of – what? – perhaps 96 years (give or take).

In 1798, 66 years of age was old: a foot in the grave old; farting dust old; walking as if treading on glass and sitting on a park bench feeding the pigeons old.

So what was “old” Joe Haydn doing in 1798? Having recently returned from his second triumphant residence in London, the Vienna-based Haydn was overseeing the first performance of his single greatest masterwork, the oratorio The Creation, even as he was thinking about the composition of his next masterwork, the oratorio The Seasons, which would receive its premiere in 1801, when he was 69-years-old.

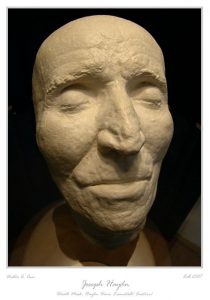

Physically, Haydn was not “cover of GQ” material: he was short (“undersized” is how contemporaries put it); his face and neck were pitted from smallpox, his bow legs were too short for his already foreshortened body, and he had a huge, beak-like nose which bent to one side as a result of a painful nasal polyp. But he had a heart of gold: a sweetness, kindness and generosity of spirit that endeared him to everyone (with the exception of his wife, who he referred to as “that infernal beast”). He had an almost child-like enthusiasm for anything new, and the boundless optimism and energy (physical, creative, and sexual!) of someone one-third his age.

Haydn returned to Vienna from his second extended stay in London in September of 1795. Immediately prior to his return, he was recorded as having said:

“I want to write a work that will give permanent fame to my name in the world.”

Incredible: as if his 104 symphonies, soon-to-be 68 string quartets, operas, trios, piano sonatas, concerti, and countless other works had not already given permanent fame to his name!

But, in fact, Haydn was referring to something quite specific. Inspired by performances of Handel’s oratorios Messiah and Israel in Egypt that he had heard in London, he wanted to compose an oratorio of equal magnificence: a work for solo voices, choruses, and orchestra that would be identified with and inspire his own Austrian “nation”.

For the subject of his oratorio Haydn chose nothing less ambitious than the creation story itself! As the story is told, while still in London Haydn asked his friend, the violinist François Hippolyte Barthélemon, to suggest a subject. Barthélemon pointed at a Bible and said:

“There! Take that and begin at the beginning.”

Before leaving London in 1795, Haydn’s producer, the impresario Johann Peter Salomon (1745-1815), acquired for him an English-language libretto entitled The Creation of the World. While the author of the libretto remains unknown, we do know that it was originally offered to Handel himself. On returning to Vienna, Haydn turned the libretto over to Baron Gottfried van Swieten, prefect of the Vienna court library and president of the Viennese educational commission. Van Swieten was himself a huge fan of Handel’s music, particularly Handel’s oratorios. (He was, as well, a friend and patron of both Mozart’s and Beethoven’s; the man hung out with some high-end talent!)

Not only did Baron van Swieten translate and adapt the libretto for Haydn, but he managed to procure for Haydn a commission for the work from a number of music-loving Viennese big-wigs, a commission that covered all performance expenses and paid Haydn a hefty fee as well.

We read that the years Haydn devoted to the composition of The Creation – 1797 and 1798 – were among the happiest of his life. Haydn had always been a devout Catholic, never plagued by doubt or skepticism. He was, at heart, an optimist, and his depiction of divine love and goodness in The Creation reflected his own religious faith as well as his optimistic world view. Haydn told anyone who’d listen that while he worked on the oratorio, he felt uplifted, inspired, and very close to his God. He told his friend Giuseppe Carpani:

“Never was I as devout as when composing The Creation. I knelt down every day and prayed to God to strengthen me for my work. When I felt my inspiration flagging, I rose from the piano and began to say my rosary. I never found that method to fail.”

The Creation was to Haydn what the B Minor Mass was to Bach, what the Ninth Symphony was to Beethoven – the capstone of his career, a massive piece for voices and instruments that expressed his essential faith in his God and his world view. That Haydn achieved the expressive effect he sought to achieve in The Creation is no better described than by Princess Eleonore Liechtenstein, who wrote her daughter after having heard its first performance 221 years ago today:

“One has to shed tender tears about the greatness, the majesty, the goodness of God. The soul is uplifted. One cannot but love and admire.”

The first performances of The Creation were held on April 29 and 30, 1798, for a specially invited audience. (The performance on April 29 was advertised as a “full dress rehearsal” but make no mistake, it did indeed constitute and was considered to be the “first performance.”)

The premiere was a scene out of the opening of an old time, big budget, Hollywood movie. The performance took place at the palace of Prince Schwarzenberg. A huge crowd of onlookers, autograph hounds, and red-carpet rug-rats gathered outside the palace. Twelve policemen and 18 armed guards were stationed around the palace to keep the crowds at bay. The lucky invitees, dressed to the nines, consisted of the highest nobility of Austria, Poland and England. Giuseppe Carpani was there:

“I was present, and I can assure you I never witnessed such a scene. The flower of society of Vienna was assembled in the room, which was well adapted to the purpose. The most profound silence, the most scrupulous attention, a sentiment, I might almost say, of religious respect prevailed when the first stroke of the bow was given.”

Haydn, ordinarily a portrait in cool, was a nervous wreck. He recalled later:

“One moment, I was cold as ice, the next I seemed on fire, more than once I was afraid I should have a stroke.”

Nothing to worry about, maestro; The Creation was a sensation. Speaking for pretty much everyone who was there, the critic for the Neuer teutsche Merkur wrote:

“Three days have passed since that incredible, rapturous evening, and still the music sounds in my ears and in my heart; still the mere memory of all the flood of emotions experienced that evening constricts my chest.”

For lots more on Haydn and The Creation, I would direct your attention to my Great Courses Great Masters biography of Haydn.

Listen on the Music History Monday Podcast

Podcast: Play in new window

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Pandora | iHeartRadio | RSS | More