When the Hamburg born-and-raised Johannes (“Hannes”) Brahms was around four years old, his father Johann Jakob Brahms decided it was high time the kid learned to play the three instruments that he himself played. Papa Brahms wanted his eldest son to follow him into the family trade and be, bless him, employable. Those three instruments were violin, cello, and the valveless, “natural” horn. The young Brahms gained a degree of competence in all three instruments, in particular the cello. However, to his father’s apparently endless annoyance, what the little fella really wanted – what he demanded! – was to learn how to play the piano. We can well imagine the conversations between father and son, played out over several years:

“Daaaaad! I wanna play the piano.”

“Hannes, dude, how many pianos are there in the Hamburg Philharmonic?”

“Uh . . . zero?”

“How many pianos in a dance band?”

“Maybe . . . um . . . one?”

“You got it. Violinists? There’s always work. Cellists? Ditto. Horn players? There are never enough decent horn players: horn players gig. Piano players? A dime-a-dozen and there’s no work. Besides, we don’t even own a piano and we don’t have the ducats to buy one. And a Casio is out of the question.”

“But Daaad, I’ll find somewhere to practice, I will, I will, I promise, you’ll see!!!”

“Dad . . . ?”

“Yes, Hannes?”

“Can we get a dog?”

This conversation (or at least ones like it) went on for three years, at which point Johann Jakob Brahms threw in the towel and found his son Johannes a piano teacher. So it was that at the age of seven Johannes Brahms began daily piano lessons with a local Hamburg teacher named Otto Friedrich Willibald Cassel, at whose home he also practiced the piano.

From that moment in 1840 until the end of his life 57 years later, Johannes Brahms was a piano player. But his love for and simpatico with the natural horn never left him. So when he sat down to compose his Horn Trio in E-flat Major in 1865 for violin, horn, and piano, he wrote the horn part for a natural horn, despite the fact that by 1865, the natural horn had been replaced by the valved horn.

Brahms’ Horn Trio is a towering masterwork, one of my very, very favorite works of music and, to my thus prejudiced mind and ear, the single greatest work ever composed for the horn.

That it was conceived for natural horn conditioned entirely the nature of the music Brahms composed, from key area to the shape and substance of his thematic melodies. Therefore, whether the piece is performed today on a natural horn or a modern horn, we must understand (and appreciate!) its glorious compositional substance – its music – through the challenges imposed by and the sound unique to the natural horn.

So please, allow me a quick and hopefully painless tutorial that will allow us to differentiate between the “natural” horn (what in Germany is called the Waldhorn) and the modern valved horn (which for reasons still not entirely clear is called in the U.S. and the U.K. the French Horn).

The ancestor of the horn is a horn: kill a horned quadruped (a ram, for example); saw off one of it’s horns; hollow it out; slice off the tip of the small end; put your lips against that hole in the small end and BRONX CHEER for all you’re worth.

By the early seventeenth century the technology of the “horn” had developed a bit. A “horn” was a gradually widening spiraled metal tube with a small mouthpiece at one end and a flared bell at the other. (For our information, the earliest surviving spiraled horn dates to about 1570.)

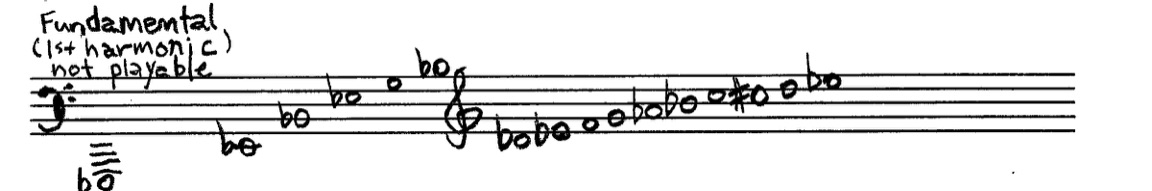

These so-called “hunting horns” can only play a single harmonic series. So a horn pitched in E-flat (for example) can only play the following pitches:

These are the so-called “open pitches” on a hunting horn pitched in E-flat.

With its profoundly limited pitch resources, such a horn is of little use in a musical setting: the owner of an E-flat hunting horn cannot, for example, play music in the key of C major. The solution – which became standard by the early eighteenth century – was the use of “crooks”: extra pieces of tubing of varying lengths that could be fitted into a horn during a long rest (though preferably between movements) that allow a player to play in different keys.

But Houston, we still have a problem. Crook or no crook, a horn pitched in E-flat still cannot play, for example, a “middle C.”…

Full post available on Patreon