The phrase “one of a kind” would seem fairly useless when applied to the arts in general or music specifically. Really, aren’t all great musical artists – by definition – “one of a kind?” Monteverdi, Purcell, Sebastian Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Wagner, Stravinsky, Springsteen, Weird Al?

Yes: these good folks (and many, many, MANY more) are indeed all “one of a kind.”

But then

But then there are those very few who are SO truly weird (sorry Maestro Yankovic; you are not really that weird), SO far out, SO iconoclastic, so radical, subversive, and idiosyncratic that they stand utterly solitary, disconnected from anything and everything but themselves; singular, detached, ALONE: truly, one of a kind.

Such a person was the American experimenter, instrument builder, guru, high priest and “composer” – and that’s “composer” in scare quotes – Harry Partch, who died on September 3, 1974 – 44 years ago today – in San Diego, California, at the age of 73.

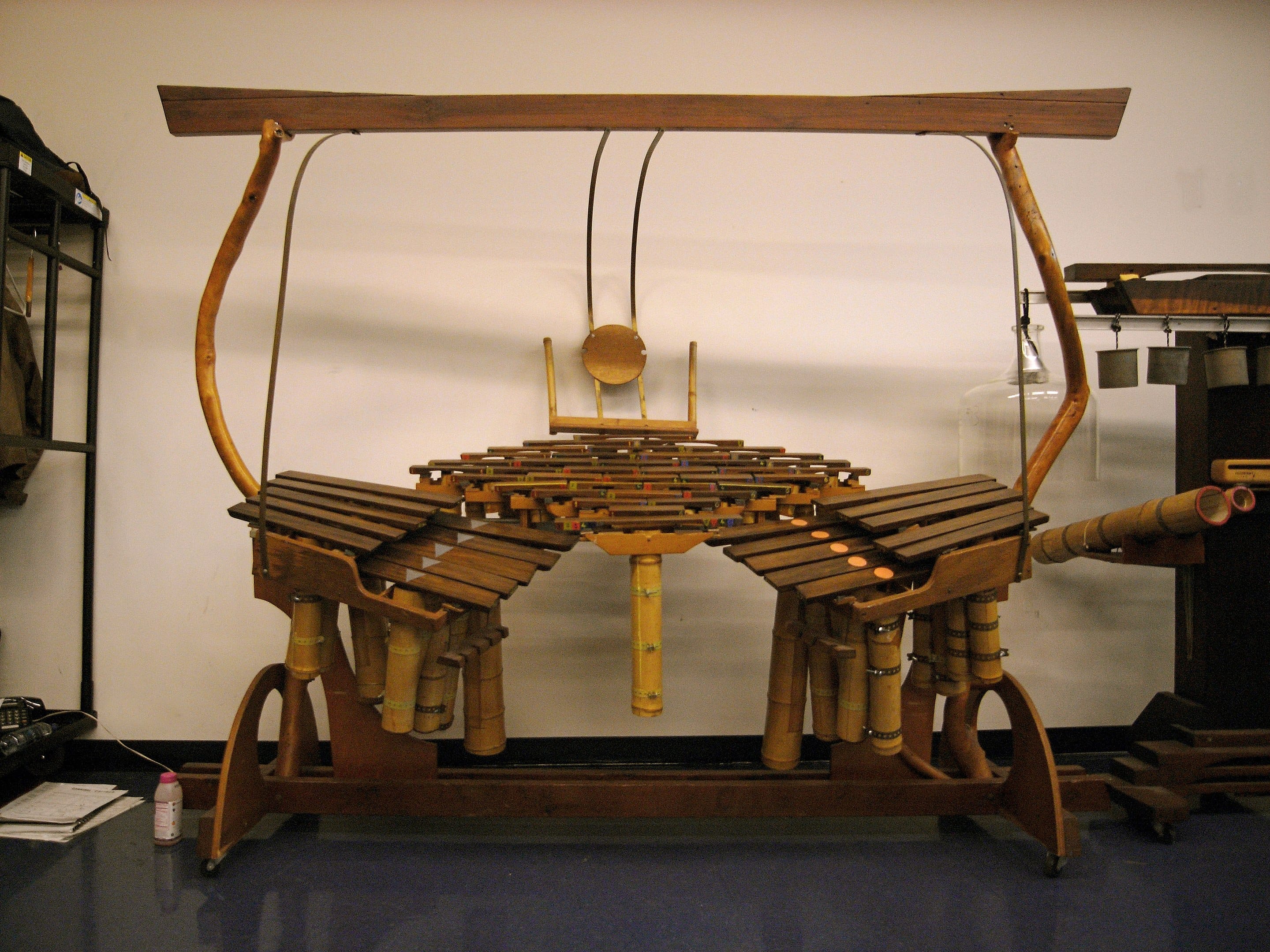

Harry Partch was one of a kind. He rejected the entire Western musical tradition and created, in its place, an alternative musical universe for which he proselytized and composed. He created a tuning system that divided the octave into 43(!) different pitches. He created a complicated, tablature-based notational system that remains almost indecipherable to anyone but one of his disciples. He designed and built a wide variety of stringed and percussion instruments capable of playing his complex tunings.

A brief word about these instruments. Whatever we think about Partch’s ideas and his music, he was an inventor and builder of genius. The instruments are strikingly beautiful, sonically gorgeous and so exotic as to make the Cantina band in Star Wars look like a drab old string quartet by comparison. In a letter to a friend, Partch described a bamboo marimba he called the “Eucal Blossom” this way:

“This is the third instrument in which I have used the contorted boughs of eucalyptus as part of the base structure. A branch with an appropriate crotch extends from a redwood base; one arm above the crotch is cut at the top and the angle desired for the disk holding the bamboo, and is there bolted to the disk; the other extends upwards through a slot in the disk and holds the music wrack.”

Partch – like so many percussionists before AND AFTER HIM – built his percussion instruments using found objects. In the case of an instrument Partch called “Spoils of War”, the “found objects” are seven artillery shells, cut to different sizes. The “Mazda Marimba” consists of 24 gradually larger light bulbs with their guts removed. (Best to play this instrument very carefully, as a heavy hand will result in a lot of broken glass!) Then there are the “Cloud Chamber Bowls”, one of Partch’s most famous creations. These are large Pyrex gongs that began their lives as Pyrex carboys: big rounded jugs with narrow necks, used for holding corrosive liquids. Partch discovered them while dumpster diving outside the radiation laboratory at the University of California, Berkeley.

My Goodness, What a Life!

Harry Partch was born on June 24, 1901 in Oakland, California at 5861 Occidental Street (the house is still there; according to Google maps it is a 14 minute drive from where I am writing these words).

He grew up in Benson, Arizona – some 50 miles east of Tucson – which was then still the Wild West. In 1919 – at the age of 18 – he moved to Los Angeles, where he studied music at the University of Southern California by day and played piano for silent movies at night. Good-looking and gay, Partch entered into a torrid love affair with a struggling actor named Ramón Samaniego. Samaniego changed his name to “Ramon Novarro”, and went on to fame and fortune as a silent movie star. But not before dropping Partch like a hot burrito. According to Partch biographer Bob Gilmore, “that experience cemented Partch’s determination to reject the mainstream in favor of the companionship of outcasts.”

Claiming that his teachers were a bunch of useless old farts, Partch dropped out of USC. He moved to San Francisco, read, composed and by 1923, had come to the conclusion that Equal Tempered Tuning was a useless and artificial construct, incapable of creating the sorts of melodic and harmonic nuance he sought. (Partch once referred to the piano keyboard as “twelve black and white [prison] bars in front of musical freedom!”)

In 1930, having concluded that the entire Western musical tradition was so much useless humbug, he burned all of his music in a pot-bellied stove.

Because of this little incendiary tantrum, Partch’s earliest surviving music dates to 1931, when he was working with a 29-pitch octave. This music came to the attention of Henry Cowell, yet another great American “one-of-a-kind”, who became something of a patron of Partch.

By 1935, Partch’s “gamut” – his 43-pitch octave – was in place and he was building instruments capable of producing those pitches. But claiming that the whole damned musical establishment – which either ignored or made fun of his music – was hum-bug, Partch again “dropped out” and chose to live a life that most folks there during the Great Depression did everything they could to avoid: he chose to become a hobo. He rode the rails, did manual labor, slept in Federal work camps or under the stars, and thought about music.

While travelling through the southern California town of Barstow, Partch spotted a bunch of “inscriptions” – graffiti – left by hitchhikers on a highway railing. He jotted them down, and they became the basis for what is considered to be one of his most important works, Barstow, composed in 1941 and then revised in 1968.

By the early 1940s Partch had given up riding the rails, though his life continued to be that of – if not a hobo – then a nomad. (I would tell you that reading Bob Gilmore’s superb biography of Partch can actually induce motion sickness, the locales change so quickly.)

Occasional academic appointments – at the University of Wisconsin at Madison, Mills College in Oakland, and the University of Illinois at Urbana – never lasted for long thanks to Partch’s bad attitude towards academia and academia’s bad attitude towards Partch. This self-described “vagabond’s” last stop was San Diego, where he died after suffering a heart attack on September 3, 1974, age 73.

Partch’s desire to create a self-described “corporeal music”, one that combined instrumental performance, singing, dance, ritual and drama was Wagner-like in its ambition. But even more than Wagner or, truly, any composer before or since, Partch also tried his best to create an entirely new musical syntax, a “new music” in which he himself – Harry Partch – was a combination high priest, guru and maestro.

To his fans, Partch was a messianic visionary. To his detractors he was a crank. But even his detractors have to admit that Partch was a very interesting crank.

For our information, Partch’s instruments presently reside at the University of Washington in Seattle.

For those wanting to know more about Partch and for a detailed examination of what is probably his most important work – Barstow – I would direct your attention to my Great Courses Survey, “The Great Music of the 20th Century”, which can be sampled and downloaded right here.

Music History Monday Podcast

Podcast: Play in new window

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Pandora | iHeartRadio | RSS | More

Robert Greenberg Courses

How to Listen to and Understand Great Music, 3rd Edition

Price range: $349.95 through $599.95 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Great Music of the 20th Century

Price range: $199.95 through $319.95 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page