Bartók’s String Quartet No. 6 was written in early 1939, at a very dark time in his personal life and in history.

Bartók’s String Quartet No. 6 was written in early 1939, at a very dark time in his personal life and in history.

Some background.

Adolf Hitler came to power when he was appointed German Chancellor – the head of the government – on January 30, 1933. The fools that arranged Hitler’s appointment did so because they thought he could be controlled. Things didn’t work out that way. By August of 1934, Hitler had outlawed all opposition political parties and assumed the mantle of the German presidency and Supreme Commander of the armed forces. There would be no stopping him and his twisted regime until his death eleven years later, in April of 1945.

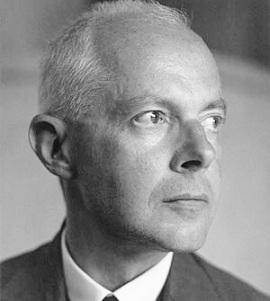

Béla Bartók – pianist, composer, Hungarian patriot and a resident of the Hungarian capitol of Budapest – observed the rise of Nazism with undisguised revulsion. When the Nazi’s marched into and occupied Austria in March of 1938, Bartók suspected that it was only a matter of time before Hungary was occupied as well. He wrote to his friend and patron, Paul Sacher:

“There is the imminent danger that Hungary will also surrender to this system of robbery and murder. How I could then continue to live or work in such a country is inconceivable.”

When Bartók wrote that letter – which clearly indicates his intention to leave Hungary if events forced him to do so – he was 57 years old and not in the best of health; his mother was quite ill, and he was the sole bread earner for his family.

In 1938, immediately following the Nazi takeover of Austria, Bartók’s Vienna-based publisher, Universal Editions, was “Nazified”. Along with his friend and colleague Zoltán Kodály, Bartók received a questionnaire from the newly Nazified publishing house, asking him about his ancestry and allegiance:

“Are you of German blood, a related race, or non-Aryan?”

Bartók later wrote:

“Of course neither I nor Kodály filled it out: such inquisitions are contrary to right and law. In a way it’s too bad, because one could make some pretty good jokes in answering. For example, we might say that we are not Aryans – because in the final analysis ‘Aryan’ means ‘Indo-European’; we Magyars, however, are Finno-Ugrics, yes, and what is more, perhaps racially Northern Turks, consequently not at all Indo-European and therefore non-Aryan. Another question runs thus: ‘Where and when were you wounded?’ Answer: ‘March, 1938, in Vienna!’”

Joking aside, Bartók’s bitterness was clear. He began making plans to leave Hungary, despite his desire to stay as long as his mother was alive.

Bartók began composing his String Quartet No. 6 in late August of 1939. Just days later, on September 1, Germany invaded Poland and the war in Europe began. Through the fall of 1939, as Bartók increasingly felt the need to leave Hungary, his mother’s illness entered its terminal stage. It was under these circumstances that Bartók completed his string quartet in November of 1939. His mother died in December. Bartók left for the United States almost immediately. The Sixth Quartet was the last work he would complete in his native Hungary.

String Quartet No. 6 (1939)

Bartók’s sixth string quartet is one of his most deeply expressive and personal works. Each of its four movements begins with the same theme and the same expressive designation: mesto, meaning “sadly”.

these four introductory passages, all based on the same lyric and melancholy theme, inform this quartet with a restraint and sadness that frames and constrains the other music in the quartet. Movements 1 and 4 take their expressive lead from this introductory Mesto, so at its outer ends – the first and last movements – the quartet plumbs a level of deep, spiritual sadness.

Of particular interest are the inner movements, movements two and three. Following the mesto introduction, the second movement – labeled “march” and structured in three-part, “A-B-A” form – opens and closes with a strange, out-of-step, almost comical little march. Given when this music was composed – during the fall of 1939 – the message here is pretty much impossible to miss. The cartoon-like strutting (or should we more accurately call it “goose-stepping?!”) of would-be conquerors is well and acidly depicted. That this march is scored for a string quartet – which is, with all due respect, not an ensemble likely to create the sort of militant punch a march demands – only adds to the irony: it is a small ensemble, depicting the actions and ambitions of small men.

At the center of the movement is a truly bizarre section of music. On its surface, it appears to be a bit of Hungarian folk-music: the ‘cello plays a folk-like tune, accompanied by cimbalom-like violins and a strumming, citera-like viola. But things are not right. For example, the ‘cello – playing at the very top of its range – is awkward and out-of-tune with the harmonies around it; and the strumming viola doesn’t quite line up with the other instruments. The fact is, Bartók is satirizing his own Hungarian musical roots, and by association, the politics of his Hungarian nation.

You see, in 1937, to Bartók’s horror, Hungary negotiated a non-aggression pact with Hitler. Among the rewards for signing the pact Hungary received some bits and pieces of Czechoslovakia when it was dismembered by Germany in 1938. Bartók’s disgust with the politics of his Hungarian nation is well illustrated by the following passage from his will, written soon after the completion of his String Quartet No. 6:

“My burial is to be the simplest possible. If after my death they want to name a street after me, or to erect a memorial tablet to me in a public place, then my desire is this: as long as what were formerly Oktogon-Ter and Korond in Budapest are named after those for whom they are at present named [meaning Hitler and Mussolini], and further, as long as there is in Hungary any square or street named for these two, then neither square nor street nor public building in Hungary is to be named for me, and no memorial tablet is to be erected in a public place.”

Back then to the second movement of Bartók’s String Quartet No. 6. The juxtaposition of the comic march with the discombobulated Hungarian music reflects Bartók’s revulsion with both Nazi militarism and his country’s acquiescence to that militarism. And remember: the March and the Hungarian “parody” music is introduced with the heartfelt sadness of the Mesto introduction, as if Bartók is saying to us, “listen: I’ve a sad tale to tell, a tale of small, bestial men and betrayal”.

The third movement of the quartet is even weirder than the second. Entitled “Burletta” (which means “Burlesque”), the movement begins and ends with clownish, almost joking music, in which the violins are asked, alternately, to purposely play a ¼ tone flat:

Taken by itself, this music might seem merely crude and perhaps a bit silly. But within the context of the entire quartet, and following on the heels of its Mesto introduction, this grotesque becomes quite ominous. Is Bartók attempting to portray his fellow Hungarians, going about their lives, eating, dancing and singing while Hitler and Stalin reduce Poland to a slag heap? Is this music a strange and terrible commentary on the “Dance with Death” Bartók’s mother was engaged in while he composed the quartet? However we interpret it, one thing is clear: it is very disturbing music, of which Bartók’s biographer Halsey Stevens writes:

“The humor of both the March and the Burletta has a bitter taste. There is no gentleness in their irony, only – and especially in the Burletta – a cutting, savage satire. Set off by the melancholy introductory theme, they illumine its grief without dispelling it. And the fourth movement, in which that theme is called upon for almost all the material, is pervaded by despair. Over it might be written: Lasciate ogni speranza voi ch’entrate – “Abandon all hope ye who enter here.”

Bartók’s mother died just a few weeks after he completed the quartet, clearing the way for his departure from Hungary. Braving wartime travel, Bartók and his wife arrived in the United States in 1940. His years in the United States were not easy ones; at the age of 59 he had to learn a new language, accustom himself to an entirely new culture, and watch from afar while Europe went up in flames. His health was bad, and in the fall of 1943 he fell ill with what turned out to be Leukemia. Through it all, his creative spirit never flagged. The works he composed in the United States include the Concerto for Orchestra, the Third Piano Concerto, the Sonata for Solo Violin, and the Viola Concerto. His first American apartment was in Queens, in Forest Hills; his last was at 309 West 57th Street, just a few blocks from Carnegie Hall. It was there that he lived – in “comfortable exile”, as he would say – and it was at Manhattan’s West Side Hospital that he died, on September 26, 1945 at the age of 64.

Thank you very much for this beautiful write-up.

A beautiful, knowing piece: helped me discover these extraordinary quartets. Thank you.