On March 18, 1902 – 117 years ago today – Arnold Schoenberg’s Verklarte Nacht (meaning Transfigured Night) for string sextet received its premiere in his native city of Vienna. Considered today to be Schoenberg’s first “major” work, the music prompted what are euphemistically called “disruptions” (meaning catcalls and hisses) and even some fisticuffs among the audience, though it evoked respect and admiration as well.

About those disruptions and fisticuffs. In fact, Transfigured Night is a fastball down the middle of the late-Romantic era musical plate. Typical of so much nineteenth century music, it is a piece of “program music”: an instrumental work that “describes” a literary story. Typical of so much late-nineteenth century German music, it employs an advanced harmonic language based on that of Wagner and Brahms. So why all the fuss at the premiere of Transfigured Night? I would suggest that much more than the music itself, that disapproval had to do with the ethnicity of its composer and the political atmosphere in Vienna in 1902. And therein lies our story.

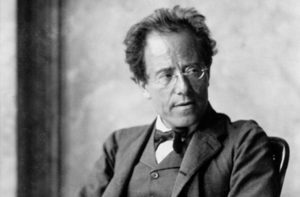

Arnold Schoenberg (1874-1951)

Schoenberg was born on September 13, 1874 in the Leopoldstadt ghetto (or the “2nd district”) of Vienna, into a poor Jewish family of Hungarian origin. His father, Samuel, was a shoemaker, and was described by a cousin as being:

“[a] freethinker, a dreamer, an anarchic idealist.”

Schoenberg’s mother, Pauline, was an observant Orthodox Jew who came from a family of cantors. In total, Samuel and Pauline had three children; Arnold was the oldest.

He began violin lessons at the age of eight, viola lessons soon after and eventually taught himself to play the ‘cello as well; he began composing when he was ten. Schoenberg’s formative musical experience was playing chamber music with his friends and extended family, and it was as a performer of chamber music that Schoenberg, the composer, was essentially formed.

What that means is that from the beginning of his musical life, Schoenberg generally perceived music “polyphonically” – as the confluence of independent melodic parts – and not harmonically, the way a piano player (or any player of a chord producing instrument) generally perceives music.

Arnold’s father Samuel died in 1890 when Arnold was 16. To help support his family, Schoenberg left school and took a job as a bank clerk, a job he held for five years. Increasingly, he supplemented his income with side jobs that attest to his rapidly developing abilities as a composer: he became a sought-after orchestrator of operettas and composer of cabaret songs.

His big break during these years – the early 1890s – occurred when he met the Viennese-born composer, conductor, and teacher Alexander von Zemlinsky (1871-1942).

Zemlinsky was a rising star on the Viennese musical scene. Three years older than Schoenberg, he had the sort of musical pedigree that Schoenberg could only dream about: he had graduated with distinction from the Vienna Conservatory and his music had been praised by none-other-than Johannes Brahms, at the time the godfather of Viennese music.

Zemlinsky took a shine to Schoenberg and became his friend and, briefly, his teacher. It was through Zemlinsky that Schoenberg – a poor Jewish kid from the wrong side of the Danube Canal – gained access to the musical heart of old Vienna. It was Zemlinsky who introduced Schoenberg to the music of Richard Wagner. It was Zemlinsky who introduced Schoenberg to a group of young musicians that met regularly at the Café Griensteidl at Michaelerplatz 2, just a block away from Emperor’s Palace.

Of the young musicians who met at the Café Griensteidl, Schoenberg’s cousin Hans Nachod later recalled:

“They were all rebels: they were unconventional in the conventional surroundings of old, traditional Vienna.”

Rebel or no, the music Schoenberg composed during the 1890s – his “decade of apprenticeship” – was relatively conventional. His earliest important works – his String Quartet No. 1, Pelleas und Melisande, and Transfigured Night – all lay within the leitmotif-dominated tonal style of Richard Wagner.

Transfigured Night, Op. 4

Schoenberg composed Transfigured Night in 1899, when he was 25 years old. He later arranged it for string orchestra, and to this day the string orchestra version of Transfigured Night remains Schoenberg’s single most “popular” composition.

Transfigured Night is based on a poem by the same name written by the German writer and poet Richard Dehmel (1863-1920). The poem describes a nameless man and woman walking together on a cold night. The first line of the poem – “Two people walk through the bare, cold grove” – is bleakly depicted by Schoenberg in the key of D Minor. The woman tells the man that she loves him but confesses that she is pregnant by another. The man tells her that his love will transfigure the child and make it his own. Thus forgiven, the woman, her unborn child, and the night are all “transfigured” – “transformed” – and the piece ends bathed in the brilliant light of D Major. The poem concludes with the line, “Two people walk through the lofty, bright night.”

A necessary editorial comment: only someone with a heart smaller than Ricky Henderson’s strike zone can remain unmoved by Dehmel’s poem and by Schoenberg’s incredibly passionate, incredibly beautiful musical interpretation of the poem.

A key point: Schoenberg’s Transfigured Night does not so much describe the physical environment and “action” of the poem as it illuminates the conscious and unconscious emotional progression of the poem’s two protagonists: the nameless woman and man.

Compositionally, Transfigured Night is about continuous melodic development and transformation, “transformation” that becomes a metaphor for the transfiguration of the night described in the poem. While this sort of “continuous variation” is something Schoenberg learned from Johannes Brahms, pretty much everything else about Transfigured Night is Wagnerian: the subject matter, its heart-rending lyricism, the use of leitmotifs, the incredible polyphonic interplay between the six instrumental parts (two violins, two violas, and two ‘cellos in its original version), and its chromatic but still functionally tonal harmony.

So back to the booing and whistling and fisticuffs Transfigured Night provoked at its premiere, 117 years ago today. Despite the fact that the piece employs a compositional syntax drawn from the two most unimpeachable exponents of late nineteenth century German music – Johannes Brahms and Richard Wagner – many contemporaries accused it of being dangerous, “degenerate” music. One critic remarked that:

“It sounds as if someone had smeared the score of Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde while the ink was still wet!”

The fact is that many in the audience and the press were not prepared to give an orthodox Jewish composer from the Second District ghetto an even break. Anti-Semitism shaped Schoenberg’s life and career to a degree that’s hard for us to imagine today. For our reference, the Dreyfus affair – which inspired Schoenberg’s fellow Austro-Hungarian citizen Theodor Herzl (1860-1904) to propose the creation of the state of Israel – occurred in 1894, when Schoenberg was twenty years old. The literary forgery entitled The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, which alleged a Jewish and Masonic plot to take over the world, was first published in 1903. The virulent anti-Semite Karl Lueger (1844-1910) was elected Mayor of Vienna in 1895 and served as mayor until his death in 1910. Adolph Hitler – who lived full-time in Vienna from 1908 to 1913 – credited this same Karl Lueger as being a formative inspiration to him.

Schoenberg’s developing cultural alienation – which no doubt helped embolden him to break away from traditional tonality some ten years after composing Transfigured Night – was in no small part a product of the ongoing alienation he felt as a Jew in Vienna.

Not everyone booed Transfigured Night. In the audience at its premiere was the most powerful man in Viennese music, the music director and principal conductor of the Vienna State Opera: Gustav Mahler (1860-1911). Mahler was a Bohemian-born Jew, a composer of the first rank and the greatest conductor of his generation. Mahler’s own existentialalienation prompted him to famously remark “I am thrice homeless, as a Bohemian in Austria, as an Austrian among Germans, as a Jew throughout the world, everywhere an intruder, never welcomed.”

Well, Gustav Mahler was knocked out by Schoenberg’s Transfigured Night, and thus began what was to be one of the most important relationships in Schoenberg’s life.

For lots more on the life and music of Arnold Schoenberg, I would humbly direct your attention to my Great Courses survey, “The Great Music of the 20th Century”.

Listen on the Music History Monday Podcast

Podcast: Play in new window

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Pandora | iHeartRadio | RSS | More