We mark the death on June 15, 1996 – 24 years ago today – of the singer and musician – the First Lady of Song, the Queen of Jazz, Lady Ella – Ella Jane Fitzgerald at the age of 78.

We contemplate singers.

I would begin by making a couple of distinctions, distinctions that might trouble any number singers. My apologies, then, in advance (though, frankly, if I was worried about upsetting singers I would never have become a composer in the first place).

Distinction one: in the world of music, there is often a divide – a big divide – between musicians and singers. A musician is someone who can not only sing and/or play a musical instrument and/or compose, but someone who knows something of music. Whether a concert violinist, a rock guitarist, an operatic soprano, or a jazz saxophonist, someone who “knows something of music” is a musician who is familiar with the repertoire and the history of her discipline, and has attained a working technical knowledge of the vocabulary of music: rhythm, melody, harmony, etc.

Many singers grow up as musicians, who studied voice and/or a musical instrument as children. But not infrequently, singers are laypeople who only discover their “instruments” – their voices – when they’re well into puberty. “You should be an opera singer!” well-meaning friends and family tell them. They sing along with records, perhaps take a few lessons, sing in their high school musical, and then decide to major in music or even attend a conservatory as a student of voice. And here’s the kicker: these not untalented but musically uninformed individuals will often be accepted into a conservatory based on the beauty and promise of their voices. Can they read music in more than one clef? Can they read music at all? It often makes no difference; they are accepted just the same.

This was a sin perpetrated constantly during my tenure at the San Francisco Conservatory, and it created two distinct classes of students: the singers and everybody else. The singers had to take the same music history, musicianship, music theory, harmony, and counterpoint classes as kids who’d been playing the violin, cello, piano, or flute their entire lives. (In addition, the singers had to take classes on diction, foreign languages, and stagecraft.) Of course the majority of them couldn’t compete; of course they struggled academically, and sometimes – painfully – crashed and burned. I hated it; every semester I’d have 2 or 3 voice students come to my office, sobbing with frustration; all I could tell them was not to worry about their grades but to just keep plugging away.

For the singers, as a community, their struggles were a badge of courage. They would snort derisively at the instrumental students, telling them: “my body is my instrument!”

Whatever their trials and tribulations, any voice student who has managed to pass a senior recital can make a claim: that he or she is a trained singer.

And there it is, the second of my distinctions: the distinction (the chasm, the gulf, the parsec distance: 3.3 light years) between a trained singer and an untrained singer.

Rarely in this whacky world of ours is a distinction as easily perceived as that between trained and untrained singers. For most people, the distinction is unimportant; it’s a matter of render unto genre what genre demands. When listening to opera, we expect and demand to hear highly trained singers. When listening to Joe Cocker, we get . . . well, the oral flatulence that is Joe Cocker.

I used to be just that sort a live-and-let-live kind of listener. But I’m getting old and sour and will admit that the sort of affectations displayed by many untrained singers to compensate for their lack of range and technique have become markedly unpleasant for me. I’ll be the first to admit that this is an unfortunate state of affairs, like no longer being able to enjoy a $7 bottle of wine. Singers I once loved for their raw authenticity I now can hardly endure. Joni Mitchell? OMG, I adored her; I was prepared to have her child. Now? All I hear is a tobacco-ravaged voice singing flat all the time. Janis Joplin? I loved Janis Joplin. Not anymore. Enough said.

Now, the very least thing any singer must be able to do – trained or untrained – is sing in tune. But thanks to technology, many modern pop divas, divos, rappers and hip-hoppers don’t have to do even that, thanks to a technology called “Auto Tune”. (“Auto Tune” is a “pitch correction” software device introduced in 1997 that digitally corrects a singer’s intonation.)

(I know it’s been out for years, and that many – if not most – of you have already seen it, but there’s a genuinely funny video featuring a Britney Spears look-a-like employing an Auto Tune-like technology that’s worth a few minutes of your time)

Who uses Auto Tune? (The better question would be who doesn’t use Auto Tune!) Users include Cher, Miley Cyrus, Kesha, Kanye West, Selena Gomez, Chris Brown, Katy Perry, Madonna, Nicki Minaj, Rihanna, Taylor Swift, Justin Bieber, Britney Spears; the list goes on. Some among us might not fault these “singers” – we all employ technology in the service of self-improvement, right? – but please, let’s be real: would Maria Callas, Joan Sutherland, Renata Tebaldi, Marian Anderson, Anna Netrebko, Luciano Pavarotti, Placido Domingo, Monsterrat Caballé, Kiri Te Kanawa, Thomas Hampson, Joyce DiDonato, Samuel Ramey, Renée Fleming, Mirella Freni, Christa Ludwig, Birgitt Nilsson, Jessye Norman, Elizabeth Schwarzkopf, Leontyne Price, Cecilia Bartoli, Edita Gruberová, Marilyn Horne, Kirsten Flagstad, Isabel Leonard (okay, I’ll stop): WOULD ANY OF THESE SINGERS EVER NEED TO EMPLOY AUTO TUNE IN ORDER TO SING IN TUNE?

The answer, of course, is no, because as professional opera singers are among the world most elite, most talented, most highly trained vocalists anywhere.

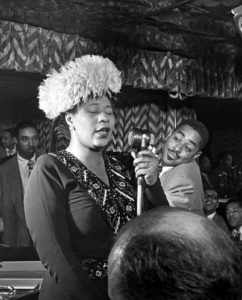

Which brings us, finally, to the strange and wonderful case of Ella Fitzgerald (1917-1996). “Strange” and “wonderful” because Ms. Fitzgerald was in a class utterly by herself. Her intonation was flawless: Fitzgerald never, ever sang out-of-tune. Her phrasing and breath control were likewise impeccable. She had a consistent and luminous vocal tone throughout her three-plus octave range. Her diction was perfection, and her voice was always centered and never strained. One moment she could sing the most heartbreaking ballad with an effortless, almost girlish sweetness that never failed to weaken a listener’s knees and the next, scat sing sounding like an entire brass section. She was an untrained singer whose voice was, nevertheless, “in a class with formally trained opera singers.”

Let’s consider that statement for a moment, “an untrained singer in a class with formally trained opera singers.” That’s an incredible, an even ridiculous statement.

Why?

Please, for a moment let’s think sports.

Whatever genetically blessed, natural athleticism they possess, professional athletes are coached – trained, taught – from day one. And that coaching – that training – never stops; it continues throughout a professional career. Despite their greatness, Mike Trout still has a hitting coach (his name is Jeremy Reed); Simone Biles has her gymnastics coach (Aimee Boorman); Tiger Woods has his swing coach (Brian Costa); and Serena Williams her tennis coach (Patrick Mouratoglou. We would no longer expect an elite athlete to be untrained than we’d expect an elite singer – “my body is my instrument” – to be untrained.

And yet the untrained Ella Fitzgerald had elite skills.

She sang without affectation, because she could. Unlike such contemporaries as Billie Holiday, Nina Simone, Sarah Vaughan, and Eartha Kitt, all of whom cultivated a personal vocal “sound” (in Eartha Kitt’s case, a “sound” bordering on shtick), Fitzgerald simply didn’t need to: the purity, clarity, flexibility, nuance and accuracy of her instrument allowed her the freedom to sing without histrionics because she could. It was a skill that awed everyone that heard her, no matter his or her musical background.

Speaking of the songs he wrote with his brother George, Ira Gershwin said:

“I didn’t realize our songs were so good until Ella sang them.”

Both Benny Goodman and Bing Crosby named Fitzgerald as their favorite singer. Crosby said:

“Man, woman or child, Ella is the greatest.”

According to Johnny Mathis, “She was the best there ever was. Amongst all of us who sing, she was the best.” Said Dionne Warwick, “she made the mark for all female singers, especially black female singers, in our industry.”

Mel Tomé called Fitzgerald “the high priestess of song,” and according to Tony Bennett, “her recordings will live forever. She’ll sound as modern 200 years from now.”

Duke Ellington addressed the often-unfortunate distinction between singers and musicians when he wrote:

“Her artistry brings to mind the words of the maestro, [Arturo] Toscanini who said concerning singers, ‘either you’re a good musician or you’re not.’ In terms of musicianship, Ella Fitzgerald was beyond category.”

Ella Fitzgerald was and is held in equal esteem by concert musicians. When asked in an interview who was her all time favorite musician, the brilliant American soprano Isabel Leonard (born 1982) gave a two word answer: Ella Fitzgerald.

The pianist and accompanist Gerald Moore (1899-1987) tells a wonderful story in his memoirs. Moore accompanied the great lieder and opera singer Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau (1925-2012) in a recital in Washington D.C. As far as Moore knew, Fischer-Dieskau “seemed to care only about classical music.” As such, Moore was that much more surprised when Fischer-Dieskau dashed offstage after the concert and explained to Moore that he had a plane to catch to New York, where Ella Fitzgerald was performing with Duke Ellington that evening at Carnegie Hall. Fischer-Dieskau gushed like a schoolboy “Ella and Duke together! Who knows whether I’ll ever get to see them together again?!”

Ella Fitzgerald was, perhaps, the supreme interpreter of the Great American Songbook, the canon of great American popular songs written between the nineteen-teens and the 1950s.

Between 1956 and 1964 Fitzgerald recorded eight albums for the Verve label, celebrating, in order, the songs of Cole Porter, Rodgers and Hart, Duke Ellington, Irving Berlin, George and Ira Gershwin, Harold Arlen, Jerome Kern, and Johnny Mercer.

According to Stephen Holden writing in The New York Times in June 1996:

“These albums were among the first pop records to devote such serious attention to individual songwriters, and they were instrumental in establishing the pop album as a vehicle for serious musical exploration.”

Tomorrow’s Dr. Bob Prescribes post will offer up a brief biography of the magnificent Ms. Fitzgerald and then will go on to recommend two of the songbook albums, with the understanding that once you’ve acquired two of them, acquisition of the other six will likely not be far behind!

Listen on the Music History Monday Podcast

Podcast: Play in new window

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Pandora | iHeartRadio | RSS | More