We recognize the birth on November 25, 1896 – 123 years ago today – of the American composer and music critic Virgil Thomson in Kansas City, Missouri.

Mr. Thomson was one of the most important American musicians and music critics of the twentieth century. But before we move on to him, we’ve an additional topic of nearly equal import with which we must deal, albeit, sadly, in a cursory fashion, here on the august and dignified pages of Music History Monday.

On November 25, 2002 – 17 years ago to this very day – the Academy Award-winning actor Nicolas Cage (born Nicolas Kim Coppola in 1964) filed for divorce from the so-called, self-styled “Princess of Rock ‘n’ Roll” Lisa Marie Presley (born 1968). The loving couple had been married for all of 107 days. The marriage ended due to what was euphemistically called “irreconcilable differences”. A brief perusal of internet tabloids (“interbloids”? “tabnets”?) would confirm the “irreconcilable” part. For his part, Cage comes up relatively clean (I’ve used the word “clean” advisedly, as Cage is known for his aversion to deodorant). Indeed: he is impetuous in his actions and spending, which resonates with the spontaneity of his over-the-top, sometimes even surreal acting style. But being impetuous is not, in itself, a particularly damning trait except when it comes to choosing a marital partner. Impetuous and ill-advised was Cage’s choice of Ms. Presley; he should have done a little due diligence over Lisa Marie, who had just recently ended her sham (illegal), public relations-stunt marriage to Michael Jackson. During the course of their “marriage” (that’s “marriage” in scare quotes), Cage and Presley never lived together because they couldn’t agree on where they wanted to live. According to Cage (and Michael Jackson before him), Presley was a jealous control freak who would phone him and harangue him constantly, to the point that Cage could not conduct business meetings or rehearsals. She once had her bodyguards physically throw him out of a recording studio because his presence “made her nervous.” But the clincher – for a fellow collector like myself – is that according to Cage, Lisa Marie “made him” sell his huge and fabled comic book collection, something he regrets to this day. “I should have stood up for myself,” says Cage.

Uh-huh. Grow a pair, says we.

I will be forgiven for the previous sentence, despite the fact that I know it was critical of me to say what I said, jumping to a conclusion – perhaps rashly – that Maestro Cage was/is cajone-challenged.

But that’s what critics do, yes? They judge and draw conclusions based on their own opinions and experience, more often than not with hardly a clue as to the true intentions of the individual or object being critiqued.

Ah, critics. We can’t live with them and we can’t live with them (you read that correctly). Having said that, I have no intention – here – of getting into a conversation/screed on the role and responsibilities of the critic; that would take up three or four entire posts and would only, in the end, showcase my own frustration with “criticism” as it is generally practiced.

(“But”, one might say, “critics help me decide what restaurants to go to and what movies to watch.” And well they might. But the soaring prose, scalpel-sharp wit, professional jealousy and personal agendas of many of the “best” critics effectively cloud their judgment and cause them – not infrequently – to overstate their critical case and to thus render their critiques as subjective as any laypersons.)

Painful to the critical community though it may be, the fact remains that the surest way for a critic to be remembered is to get it wrong.

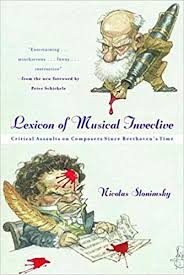

There is a wonderful book that I cannot live without entitled Lexicon of Musical Invective: Critical Assaults on Composers Since Beethoven’s Time, gathered and edited by Nicolas Slonimsky, which catalogs many of the very worst things said about all our favorite composers. For example, we all know Beethoven’s opera Fidelio to be a masterwork, and so a positive review of the opera merely reinforces what we already know. But a rotten review, well that’s worth quoting, because the critic is so wrong. This is what August von Kotzebue wrote of Fidelio in the Viennese publication Der Freimütige on September 11, 1806:

“Recently there was given the overture to Beethoven’s opera Fidelio, and all impartial musicians and music lovers were in perfect agreement that never was anything as incoherent, shrill, chaotic, and ear-splitting produced in music. The most piercing dissonances clash in a really atrocious harmony, and a few puny ideas only increase the disagreeable and deafening effect.”

Question: would there be any reason to remember August von Kotzebue here in 2019 other than this review? Nope.

(For everyone’s information, Nicolas Slonimsky’s Lexicon of Musical Invective will be the topic for Dr. Bob Prescribes in two weeks, on December 10.)

Now I will be the first to admit that it’s often downright fun to read a really well written bad review. For just such a review I would direct your attention to Pete Wells’ categorical destruction of Peter Luger Steak House in Brooklyn, N.Y. in a review in the New York Times on October 29 past.

Entertaining though such reviews may be to read, they can be devastating, particularly when directed at an individual. I’ve said it before, and I’ll say it again: anyone who says that “there is no such thing as a bad review” has never gotten a bad review. Bad reviews, in fact, suck. Every time. Always. Forever. As for so-called “constructive criticism”, to paraphrase Lorenzo da Ponte’s libretto of Mozart’s Così fan Tutte, “constructive criticism is like the phoenix; everyone says it exists, but no one has ever seen it.”)

One might think that the best critics would be practitioners themselves: professional composers, artists, writers, film makers, painters, etc. Yes, one might think. But I would argue the opposite, and I personally had the opportunity to do so some 24 years ago. I was, at the time, a professor at the San Francisco Conservatory, where I was Chair of the Department of Music History and Literature and Director of the Adult Extension Division. It was in my capacity as Director of the Extension that I created a lecture series featuring present and former music critics living here in the San Francisco Bay Area. The first such featured critic was Robert Commanday (1922-2015), a Harvard and Juilliard-trained musician who was the chief music critic for the San Francisco Chronicle from 1964 until his retirement in 1993. I met with Commanday in 1995 at his nearby Oakland Hills home and persuaded him to participate in the lecture series. He, in turn, attempted to persuade me to participate in what was then a startup venture: an internet site to be called “San Francisco Classical Voice,” a site that would do what print journalism was no longer doing, that being to review the entire gamut of concert music – in particular new music – here in the San Francisco Bay Area. Referencing such notable composers-cum-critics as Hector Berlioz, Robert Schumann and Claude Debussy, Bob asked me to sign on to his venture as a critic on the new music scene. I retreated from his offer as quickly as I would a tongue kiss from an alligator. “Not on your life” I no doubt vehemently replied, or something to that effect. Commanday – who I knew fairly well – angrily called me a coward. He was being unkind, but he wasn’t wrong. As I pointed out to him, I had to live and work in the local new music community. The composers and performers I would be reviewing were, in many cases, my colleagues and my friends or possible future colleagues and friends. There was no way I was going to be a hoopoe bird, a bird – I once read – that is purported to foul its own nest. There was no way I was going to “foul my own nest” by reviewing the work of my colleagues. And that was that.

But there were other, less personal and more altruistic reasons why I could never work as a critic. I am aware that contemporary professional composers compose the way they do because they’ve found/created a musical language that works for them. But creating my own musical language has also meant discarding and abandoning those syntactical elements that do not work for me, which raises the dilemma: how could I, as a critic, honestly critique music that goes against my own musical grain, music that embraces a syntax and expressive content that I have personally rejected? Would I be big enough, mature enough, and fair enough to look beyond my own prejudices and critique such music strictly on its own terms?

Hell no. And in this I wouldn’t be alone; the aforementioned Hector Berlioz, Robert Schumann, and Claude Debussy all used their bully pulpit in the press to attack composers whose music they didn’t “like” and to promote composers whose music resonated with their own.

Which brings us, finally, to Virgil Thompson, who was introduced at the top of this post as a composer and music critic.

Thomson was an excellent composer who wrote two important operas with Gertrude Stein early in his career and who, along with Aaron Copland, is responsible for creating what today we understand to be the “American sound” in concert music: a neoromantic compositional style that evokes a stereotypical American “sound” through the use of American folksong and folk-like music. We will explore Thomson’s life, his compositional career, and his Symphony on a Hymn Tune in tomorrow’s Dr. Bob Prescribes Post, which will be published at Patreon.com/RobertGreenbergMusic.

For now, we would take a brief look at Thompson’s career as a critic, and the degree to which Thomson was able to negotiate the inherent conflict of interest by being both a practitioner and a critic of his fellow practitioners.

Thomson was the music critic for The New York Herald Tribune for 14 years, from 1940 to 1954. His stated aim as a critic was:

“To describe what one has heard is the whole art of reviewing. To lead your reader step by step from the familiar to the surprising is the height of polemical skill. Language is for telling the truth of things.”

As a professional composer, Thomson professed to being:

“unimpressed by the trappings of celebrity performers and unemotional about the composer icons of music’s past.”

Thomson always gave the actual “music” pride of place in his reviews and not the performers. He was markedly impatient with the “50 masterwork canon” as it was regarded during his tenure as a critic, and he was unrelenting in his criticism of the New York musical establishment’s neglect of new music. He wasn’t perfect; according to his fellow critic Robert Miles, “he was capable of being vindictive and of settling scores in print.” According to the musicologist Suzanne Robinson, Thomson was motivated by “a mixture of spite, national pride, and professional jealousy”. (One suspects that Robinson, who did her doctoral work on English music, is personally miffed by Thomson’s storied dislike of the music of the English composer Benjamin Britten.) According to Joshua Kosman, presently the chief music critic for the San Francisco Chronicle, Thomson was:

“a virtual paragon of how not to practice music criticism.”

True, perhaps, but only if we consider Thomson as a “traditional” music critic, which he was most certainly not. He was a practitioner, with a personal and professional stake in the music scene as it existed at the time. And given the overwhelmingly positive impact his writing had – particularly in promoting new American music and in creating a new and more positive paradigm for American music vis-à-vis the European “standards” – we must measure Thomson’s critical career as a smashing success. In the end, Thomson should be considered not so much as a critic but rather, as an influencer.

Tomorrow in Dr. Bob Prescribes, Virgil Thomson’s life and his Symphony on a Hymn Tune.

For much more on the music of the twentieth century, I would direct your attention to my Great Courses/Teaching Company survey, The Great Music of the Twentieth Century, which can be examined and downloaded at RobertGreenbergMusic.com, and to my Patreon channel at Patreon.com.

Listen on the Music History Monday Podcast

Podcast: Play in new window

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Pandora | iHeartRadio | RSS | More