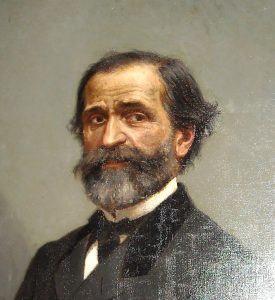

Yesterday’s Music History Monday post observed the premiere of Giuseppe Verdi’s opera Nabucco on March 9, 1842. Staying with Verdi, today’s Dr. Bob Prescribes post deals with Verdi’s least-known masterwork: his String Quartet in E minor of 1873.

The winter and spring of 1861 saw the not quite 48-year-old Giuseppe Verdi composing the operatic potboiler La Forza del Destino, “The Force of Destiny.” The majority of this four-act gore-fest takes place in Spain, and its characters and story line are Spanish. Given its Spanish locale, characters, and story, Verdi’s librettist on the gig – Francesco Maria Piave (1810-1876; Piave also write the libretti for Verdi’s Ernani, I due Foscari, Attila, MacBeth, Il corsaro, Stiffelio, Rigoletto, La Traviata, and Simon Boccanegra) – asked Verdi if he wanted to take a look at a collection of Spanish folksongs he had borrowed from a friend.

We can well imagine Piave’s offer: “You know, Giuseppe, the opera’s got a Spanish locale, characters, and storyline, and since it’s been four years since you wrote any music I’m thinking that some Spanish folksongs might give you a little inspiration, maybe help you to add a little local color, whatever. I’d like to bring them over so that you might check ‘em out.”

We do not have to imagine Verdi’s reply, as we have the letter he wrote in response to Piave’s offer:

“Do not bring the songs, and give them back to the person who lent them to you. I am not in the habit of studying music, and so I don’t keep any in the house, nor do I go looking for any from someone who has some.”

Verdi’s surprising-bordering-on-shocking reply – that he kept no music in his house at Sant’Agata (which he bought in 1848) – is not entirely accurate. What he should have said was that he kept no vocal music in his house: no songs or operas. What this reveals is that by the age of 48, Verdi was no longer interested in studying the operas of any other composer, having come to a point in his career where his compositional technique and aesthetic style were fully developed and self-defined. Verdi likely believed that such “study” could only hinder his own imagination, cramp his own style, intrude on his own voice, and thus dilute his own creative impulses.

However, Verdi did have some music in his house, in a smallish, approximately four-foot-high bookshelf at the foot of his bed, on the top shelf of which are scores of the string quartets of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven. These string quartet scores constituted his entire music library, and they can be seen today by visiting the Villa Verdi in Sant’Agata (where, sadly, no photographs are allowed, which is why I’ve had to use a borrowed photo of the bookshelf in this post!).

(For our info, the other books on Verdi’s bedroom/office/music studio shelf include Shakespeare’s complete works in translation by Giulio Carcano; the complete works of Dante; Schiller’s plays, translated by his friend Andrea Maffei; Milton’s Paradise Lost; the works of Byron translated by Carlo Rusconi; the King James Bible; and French and Italian dictionaries.)

Okay; we can understand Verdi’s desire not to be influenced by the vocal music of other composers. But why own scores of just string quartets? Why not symphonies, concerti, piano sonatas, trios, quintets, and so forth?

Here’s why. As a compositional vehicle, the string quartet is the ultimate challenge: a timbrally homogeneous ensemble consisting of four voice-like instruments (two violins, a viola, and a cello), arrayed like a choir of human voices (SATB, or soprano, alto, tenor and bass), in which each voice is an independent entity that nevertheless contributes to a whole greater than its individual part.

String quartets demand a purity of expressive conception and a compositional technique that goes beyond that required by any other instrumental ensemble (as someone who has thus far composed five string quartets, I stand comfortably by that statement). Which is why composers like Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven (whose quartets Verdi owned) lavished so much of their time and creative energy on their quartets.

It should come as no surprise, then, that Verdi’s only extended instrumental work is indeed a string quartet, the existence of which we owe to pure, dumb luck.… See the story, and Dr. Bob’s Prescribed recoding, only on Patreon!