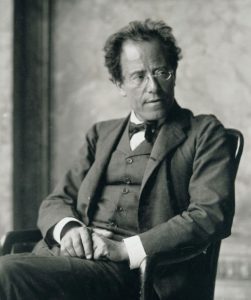

Mahler’s first four symphonies, composed between 1888 and 1901, are “program symphonies”: multi-movement works that tell an extra-musical, literary story. In order to help his audience follow those “stories”, Mahler (1860-1911) prepared written “programs” for each of his first four symphonies. For example, in reference to the titles he gave the movements of his Symphony No. 3 (“Pan Awakes, Summer Marches In”; “What the Flowers in the Meadow Tell Me”; “What the Animals in the Forest Tell Me”; “What Man Tells Me”; “What the Angels Tell Me”; “What Love Tells Me”) Mahler wrote the conductor Josef Krug-Waldsee:

“These titles can certainly be instructive. . . [They represent] an attempt to give non-musicians some point of reference or signpost to suggest the ideas, or rather the mood, of the individual movements and their relationship to each other and to the whole. They also give a hint of how I conceived the increasingly articulate expression, which proceeds from the muffled, static and merely rudimentary existence (of the forces of nature) [in the first movement], to the tender image of the human heart, which reaches towards God [in the final movement].”

Nevertheless, in that same letter to Krug-Waldsee, written during the summer of 1902, Mahler wrote apropos of his movement titles:

“I realized all to soon that my [titles] had failed (and indeed, could never succeed) and had merely given rise to the worst kind of misinterpretation. The same misfortune has befallen me on previous occasions, and I have since definitely rejected all commentaries, all analyses and every sort of guide!”

(Dude would have hated my WordScores!)

To that end, Mahler created but then refused to publicly release the program for his Symphony No. 4 of 1901, writing:

“Down with programs, which are always misinterpreted! The composer should stop giving the public his own ideas about his work; he should no longer force listeners to read during the performance and he should refrain from filling them with preconceptions. If he has succeeded in conveying the feelings that flow from him like a river, then he has achieved his aim.”

Okay; we understand that no one likes being “misinterpreted”, but I do believe that Mahler might have helped his audience a bit had he been willing to get down off his high horse and at least give them an inkling of his expressive intentions by writing program notes. But he was unwilling to do even that. In an undated letter to music critic Ernst Otto Nodnagel, Mahler wrote:

“I am and remain fundamentally opposed to all analyses, good or bad. No one can help the audience. They alone can help themselves by listening again and again and by studying the score again and again. That alone. If they cannot or will not, they should leave me in peace. Fortunately for me, my vocation is only to write music, not write about music.”

Despite his unwillingness to share his musical thoughts with his contemporary audience, we, today, have no problem knowing what Mahler works are actually “about”. That’s because we have access to his letters and the reminiscences of his friends and colleagues: we know what he said in private about his music and consequently, we (as opposed to Mahler’s contemporaries) are well-armed when approaching the programmatic content of his music.

The great Mahler scholar Donald Mitchell suggests that Mahler’s refusal to provide programs starting in 1901 was a direct response to the composition of his Symphony No. 5, which he began that year and completed in 1902. Starting with his Fifth Symphony, Mahler’s work becomes distinctly autobiographical, to the degree that, according to Mitchell:

“[Mahler himself] becomes the program of his own symphonies.”

Having said that, it goes without saying that Mahler rejected autobiographical interpretations of his music as well, although he was willing to (correctly) admit that:

“Since Beethoven there has been no music without an inner program.”

So phooey on you Mr. Mahler, we will indeed read your Sixth Symphony as having an autobiographical “inner program,” a program that is laid out in the WordScore, the first two movements of which will be posted on Thursday, November 19.…

Continue reading, and see the prescribed recordings, only on Patreon!

Become a Patron!