Mahler composed the great bulk of his Symphony No. 3 during the summers of 1895 and 1896. (Mahler was a “summer break” composer, who had to work around his conducting schedule.)

It is a huge, sprawling, 6-movement work, roughly 100 to 105 minutes in performance. (The recommended performance, conducted by Claudio Abbado, runs 102 minutes and 42 seconds: that’s 1 hour, 42 minutes, and 42 seconds.) Not only is the third Mahler’s longest work, it is also the longest symphony in the standard repertoire.

(For our information, Mahler originally intended the symphony to be longer: he planned to include a seventh movement, an orchestral setting of the song “The Heavenly Life.” In the end he chose not to include the song here in the Third Symphony; instead it became the fourth and final movement of his Symphony No. 4.)

Among the many things Mahler told Natalie Bauer-Lechner about his Third Symphony-in-progress was its programmatic plan, a plan he later withdrew and wished to god he’d never mentioned at all. Nevertheless, it is the key to understanding his expressive intentions and the dramatic progression of movements as the symphony unfolds, and we press it joyfully to our collective bosoms in gratitude.

Mahler’s programmatic plan evolved over time, and it’s thanks to Natalie Bauer-Lechner that we can observe that evolution and therefore, the gestation of the symphony.

For example.

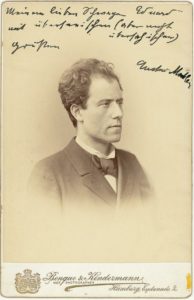

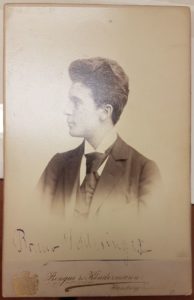

On July 2, 1896, Mahler wrote a letter inviting his friend and protégé, the conductor Bruno Walter, to join him at his summerhouse at Steinbach am Attersee, in north-central Austria on the eastern bank of Lake Atter (“Attersee”).

Writes Walter:

“[Mahler’s] cheerful letter proved that the completion of his Third Symphony had put him in good spirits. I arrived by steamer on a glorious July day; Mahler was there on the jetty to meet me, an despite my protests, insisted on carrying my bag until he was relieved by a porter. As on our way to his house I looked up to the Höllengebirge, whose sheer cliffs made a grim background to the charming landscape, he said: “You don’t need to look – I have composed all this already!

“He went on to speak of the first movement, entitled, in the preliminary draft “What the Rocks and Mountains Tell Me.”

That was Mahler’s original concept of the first movement, and the jagged, craggy, funeral march-like music that dominates its opening – “the heavy shadow of lifeless nature, of as yet uncrystallized, inorganic matter”, according to Mahler – dominated his early expressive thinking. But that conception changed as he composed the remainder of the movement, and it’s thanks to Bauer-Lechner that we’re aware of those changes. In the end, the wild, 45 minute-long, extravagantly extroverted, often magnificently banal oom-pah music that dominates the remainder of the movement (music described by musicologist Paul Bekker as “clap-trap”; Derryck Cooke as “a total formal failure”, and critic Desmond Shaw-Taylor in the Sunday Times as “an artistic monstrosity”) changed Mahler’s thinking about its overall meaning. In the end, Mahler entitled the first movement “Pan Awakens: Summer Marches In.”

Mahler told Natalie Bauer-Lechner:

“’Summer is Moving In’ is to be the prelude [first movement]. There, to attain the rough effect of my martial fellow, I immediately need a military band. With a sweeping march tempo it roars, closer and closer, louder and louder, swelling like an avalanche, until all the loud, jubilant noise engulfs you.”

The remaining five movements – which together constitute the second large “part” of the symphony – reflected Mahler’s personal emotional life (in Mahler’s own words, “what things tell me”, italics Mahler’s). As such, Mahler eventually entitled the remaining movements as follows.

II. What the flowers tell me

III. What the animals tell me

IV. What mankind tells me

V. What the angels tell me

VI. What love tells me

The sort of length and “personalization of expressive content” we are witness to in Mahler’s Third goes completely outside the symphonic box as it was understood in the late nineteenth century. Mahler understood this, telling Natalie Bauer-Lechner:

“Calling it a ‘Symphony’ is actually incorrect because in no way does it adhere to the usual form. But, in my opinion, creating a symphony means to construct a world with all manner of techniques available. The constantly new and changing content determines its own form.”

That it does, and it takes a special sort of conductor and orchestra to be able to pull off Mahler’s Third. Perhaps more than any other symphony in the repertoire, a conductor has to “get inside the composer’s head” (that’s gonna leave a mark!) in order to understand and project the megalomaniacal mixture of profundity and banality that is Mahler’s symphonic vision in his Symphony No. 3. … see Dr. Bob’s Prescription for a composer and orchestra that does pull it off, and more, only on Patreon!