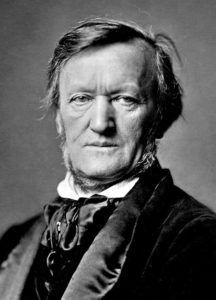

We have some heavy preliminaries to discuss, starting with the differences between European film music and the classic Hollywood symphonic film score (of which Williams is its greatest contemporary exponent); the relationship between Williams’ scores and the music of Richard Wagner (1813-1883); the derivative nature inherent to the vast majority of film music (including Williams’); and the criticism levelled at film music and film composers by the “traditional” musical establishment.

Generally but accurately speaking, European film music is discontinuous: there will be long swatches of time during which there is no music at all, particularly during dialogue. (On these lines, according to the great Italian film composer Ennio Morricone – 1928-2020 – who composed over 400 film and television scores, including those for Sergio Leone’s “Spaghetti Westerns”:

“Our hearing, and therefore our brains, cannot listen [to] and understand more sounds of a different nature simultaneously. We will never understand four people speaking at the same time. It is absolutely necessary, if the director wants to consider music in the right way, to isolate music and give the audience the time to listen to it in the best way.”)

Generally but accurately speaking, then, European film music is not synchronized with action sequences or used as a background. Instead, musical episodes are isolated from one another and are perceived as individual “set pieces”, used – like an aria in the opera house – to flesh out and deepen expressive content during gaps in the action.

Classic Hollywood symphonic film scores – by such composers as Max Steiner (1888-1971), Bernard Herrmann (1911-1975), Miklós Rózsa (1907-1995), Dimitri Tiomkin (1894-1979), Elmer Bernstein (1922-2004), Gerry Goldsmith (1929-2004), and John Williams (born 1932) – could not be more different from the European model.

Like the music dramas of Richard Wagner (1813- 1883), the classic Hollywood film score features continuous music, the use of leitmotif, music synchronized to the action “on stage”, and an expanded expressive role for an expanded orchestra.

One at a time.

Continuous music. Hollywood film scores are about almost continuous music: music that does not just paint broad scenic “pictures” and accompany action sequences, but continues quietly even during dialogue, breaking into the open during conversational lulls.

(Having said that, even John Williams knows that there are moments in a movie that are best left without musical accompaniment. Steven Spielberg, speaking at the ceremony for John Williams’ AFI/American Film Institute Lifetime Achievement Award, put it this way:

“Great composers like John know that the power of music also lies in the absence of music.”

However, we would note that such an absence is the exception, not the rule, in a John Williams score!)

Leitmotif. A “leitmotif” is a motive or a melody that is associated with a particular person, emotion, or thing, that is used to evoke that person, emotion or thing. That person, emotion, or thing need not be physically present on stage or screen when a leitmotif is used; the leitmotif itself is enough to evoke its existence.

For example. The opening of the movie Jaws features a low, ominous, increasingly fast, ever louder melody consisting essentially of a two-note motive, which at the very beginning of the movie is associated with the shark (indelibly stamping on our ears for all time what a great white shark “sounds like”). Its lowness invokes the subsurface depths in which the beast lurks. The simplicity of this repeated, two-note idea and its mechanical rhythms render the theme as unthinking and remorseless as the shark it portrays, the “perfect killing machine” as later described in the movie. Once the association between the music and the shark is made, we as an audience do not have to see it to know that it is stalking its prey: an innocent child playing in the surf and the shark leitmotif in the soundtrack is all we need to know that disaster is but seconds away.… continue reading, only on Patreon!

Become a Patron!