It is cliché but true: the older we get, the more most of us realize how little we know and how much there is still to learn. Getting older has a way of humbling us if, indeed, we are lucky enough to get older. Now, I am aware that some “older” people – particularly older academes who, believing they have mastered that narrow range of information they call their “field” – swell with arrogance when dealing with the uninformed novices that are their students and the ignorant hoi-polloi, which qualifies as everybody else. But such irksome creatures are, in my experience, relatively few and far between, and we need pay them no mind (unless we work for one or, heaven forbid, are married to one!).

I bring this up because 25 years ago even I, your humblest of intellectual servants, suffered from the sin of informational pride: I believed that I was familiar with the great bulk of the Western concert repertoire. How wrong I was. What I “knew” were the staples, the chestnuts, and a number of sleepers, and while no one can possibly “know” the entire repertoire – it is almost inconceivably vast – it turns out that I didn’t even know all the chestnuts.

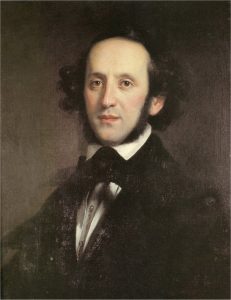

As such, I didn’t become familiar with today’s featured Mendelssohn work until this past summer. Okay; my bad.

Felix Mendelssohn paternal grandfather was the Jewish philosopher Moses Mendelssohn, who has been referred to as the “father of Reform Judaism.” Observes Mendelssohn biographer R. Larry Todd:

“Moses Mendelssohn’s struggle to mediate between two German worlds – the dominant Christian society and the disenfranchised Jewish subculture – was not lost on Felix Mendelssohn, who, after his boyhood baptism as a Protestant, remained mindful of his Jewish roots.”

In 1795, Moses Mendelssohn’s eldest son Joseph founded a private bank. In 1804 – four years before Felix was born – his father Abraham (Joseph Mendelssohn’s younger brother), joined the business. Headquartered in Berlin, the firm of “Mendelssohn Brothers & Co.” became one of the most important banking houses in all of Europe, and remained so until 1938, when it was “Aryanized” by the Nazis and forced it to sell its assets to Deutsche Bank.

Mendelssohn’s mother Lea Salomon was a native Berliner. Her grandfather was a banker named Daniel Itzig, who in 1761 became only the third Berlin Jew to receive the status of “general privilege”.

Jews in Berlin we classified into six categories. Those families in the top category – “general privilege” – were allowed to own property, found businesses, and to pass these privileges down to their children. Thus, Lea Salomon, who was smart and talented in her own right, came with what amounted to a “hereditary title” (“general privilege”), making her all together one heck-of-a great catch.

The high-end German Jewish community in which the Mendelssohns and Salomons lived placed a premium on assimilation. The perception among Germany’s small class of privileged Jews was that Judaism had become irrelevant and that remaining Jewish was socially and economically nonsensical. The answer was conversion to Christianity and complete assimilation into German society.

Lea’s brother Jacob Levy Salomon was among the first of their generation to convert (for which he was disowned by his mother, Bella). Jacob took as his new, non-Jewish surname the name “Bartholdy”.

Jacob played a major role in convincing Abraham and Lea to Baptize their four children – Fanny, Felix, Rebecca, and Jacob – which took place at Berlin’s Jerusalemkirche, near the Gendarmenmarkt, on March 21, 1816. The name “Bartholdy” was attached to their names, as it was to Abraham’s and Lea’s names as well when they themselves converted six years later, in 1822.

According to Mendelssohn’s contemporary, the poet Heinrich Heine – who was a German Jew who also converted to Lutheranism – conversion was:

“The ticket of admission into European culture, although one not regarded as valid by everyone.”

Isn’t that the truth. These smart, talented, upwardly mobile, cosmopolitan German Jews thought that by converting they could re-invent themselves and by doing so, deflect the rampant anti-Semitism of the time. In truth, the conversions didn’t fool anybody. Mendelssohn’s conversion certainly didn’t deflect Richard Wagner’s hatred for “the Jew Mendelssohn”; we are told that:

“Typical of Wagner’s overt disdain of the Jewish Race was his habit of conducting the music of Mendelssohn only while wearing gloves. At the end of the performance he would remove the garments and throw them to the floor, to be removed by the cleaners.”

Conversion didn’t keep the Mendelssohn banking business from being “Aryanized” and stolen from the family. Mendelssohn’s conversion didn’t keep his music from being banned as “degenerate” by the Third Reich or save any of the memorials to him in his native Germany. For example: in 1937, immediately prior to the 90th anniversary of his death, the city fathers of Leipzig saw to it that a monument to Mendelssohn was removed from the Gewandhaus, destroyed, and sold as scrap.

Despite his conversion and his attempts to assimilate, it is clear from his own letters and words that Mendelssohn never forgot that he was a Jew. Neither did the world around him.… Continue reading and learn about the prescribed work and recording, only on Patreon!