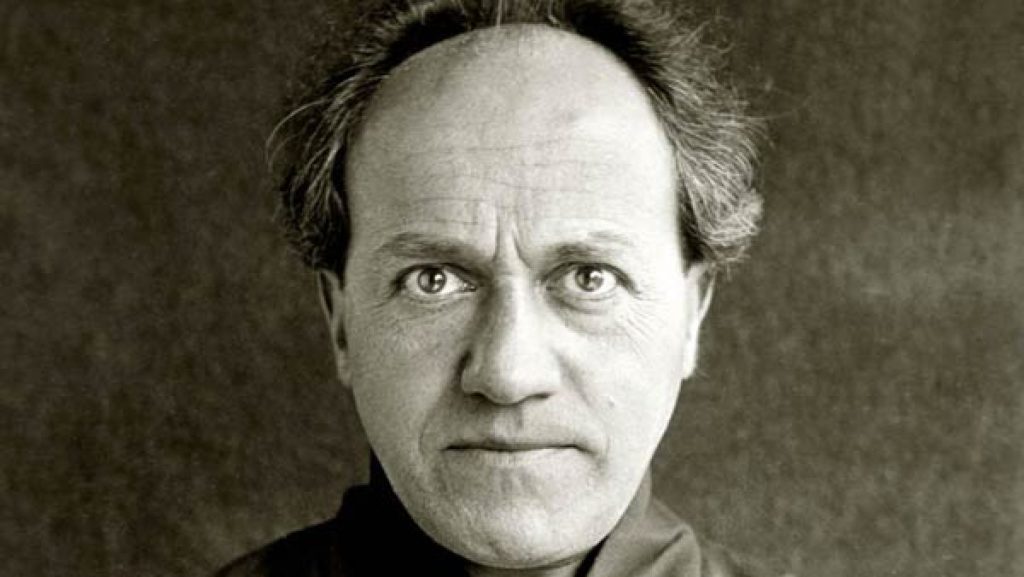

The composer, conductor, pianist, violinist, watercolorist, photographer, and teacher Ernest Bloch (1880-1959) was born 143 years ago yesterday in Geneva, Switzerland. He grew up in a middle-class household; his father Maurice Bloch was a merchant and his mother Sophie (née Brunschwig) was a highly cultured, stay-at-home mother. The Bloch’s were Jewish, and both religious and cultural Judaism played a powerful role in Bloch’s childhood.

(A brief explanation here. Many Jews, particularly Reform Jews like myself, differentiate between our cultural background and our religious background. Judaism is a very ancient way of life-slash-religion; the current Hebrew year is 5783. That’s a long time and it encompasses a lot of history, a lot of art and literature, a lot of human experience, a lot of food, and a lot of guilt. More than just a form of worship, then, Judaism is a cultural way of life and a moral code of conduct based on the Golden Rule of “do unto others as you would have them do unto you,” or so believe secular Jews like myself. This is why people like me – who are nonbelievers [or nearly so] – can still identify powerfully as Jews, despite the fact that ultra-religious Jews reject folks like me as being the lowest of trayf – “trash.”)

So back to the statement above: the Bloch family were Jewish, and both religious and cultural Judaism played a powerful role in Bloch’s childhood. So imprinted as a child, religious and cultural Judaism played a profound role in Bloch’s artistic life. Despite the fact that only around a 25% of Bloch’s approximately 100 mature compositions have some sort of Jewish reference, it is his so-called “Hebraic” works that defined his musical style and remain among his most famous.

From Bloch Himself:

“I am a Jew. I aspire to write Jewish music because it is the only way in which I can produce music of vitality – if I can do such a thing at all.”

As that previous quote demonstrates, Bloch was more than willing to talk about his “Hebraic” music and its inspiration. That inspiration was, for Bloch, a mystical attachment to his heritage, a mystical attachment he responded to at a profound psychological level:

“It is the Jewish soul that interests me, the complex, glowing, agitated soul that I feel vibrating throughout the Bible: the freshness and naiveté of the Patriarchs, the violence of the books of the Prophets, the Jew’s savage love of justice, the despair of Ecclesiastes, the sorrow and immensity of the Book of Job, the sensuality of the Song of Songs. It is all this that I strive to hear in myself and to translate in my music—the sacred emotion of the race that slumbers deep in our soul.”

Writing in his excellent Introduction to Contemporary Music, second edition (W.W. Norton, 1979), Queens College Professor Joseph Machlis (1906-1998) observes:

“Given in equal degree to sensuous abandon and mystic exaltation, Bloch saw himself as a kind of messianic personality. Yet the biblical vision represented only one side of Bloch’s art. He was also a modern European and a sophisticate, a member of an uprooted generation in whom intellect warred with unruly emotion.”

Without any doubt, it was his Jewish music that rooted this otherwise uprooted member of the Jewish diaspora, someone who lived long enough (until 1959) to see the world of European Jewry in which he grew up destroyed by the Nazis.

An important point. In creating his Jewish/Hebraic music, Bloch did not turn to the stereotypical folk idioms and Klezmer (dance) music of Eastern European Jewry for his inspiration; far from it, in fact. Rather, it was his spiritual affinity with Jewish history, liturgy, and the Bible itself that inspired him.

“It is not my desire to attempt a ‘reconstitution’ of Jewish music. It is the Jewish soul that interests me, the complex, agitated soul that I feel vibrating throughout the Bible.”

In 1938, Bloch wrote an article for the short-lived journal Musica Hebraica, which was published by “The World Centre for Jewish Music” in Jerusalem. In his article, Bloch further explains the artistic and religious expressive impulse that inspired his so-called “Jewish works”:

“In my works termed ‘Jewish’ – my Psalms, Schelomo, Israel, Three Jewish Poems, Baal Shem, The Sacred Service, The Voice in the Wilderness – I have not approached the problem from without – by employing melodies more or less authentic (frequently borrowed from or under the influence of other nations) or ‘Oriental’ formulae, rhythms, or intervals, more or less sacred!

No! I have but listened to an inner voice, deep, secret, insistent, ardent, an instinct much more than cold and dry reason, a voice which seemed to come from afar beyond myself, far beyond my parents.

This entire Jewish heritage moved me deeply; it was reborn in my music. To what extent it is Jewish, to what extent it is just Ernest Bloch, of that I know nothing. The future alone will decide.”

As we observed in yesterday’s Music History Monday, the “future” has thus far not been particularly kind to the music of Ernest Bloch, in that audiences today are largely ignorant of his music and therefore unable to decide to what extent his music is Jewish or just Ernest Bloch.…

Continue reading, only on Patreon

Become a Patron!