I am frequently asked “who is my favorite composer?” My typical response – flippant but not insincere – is that I am a musical slut: I love whomever I’m with at the moment. I mean, really: when listening to Sebastian Bach’s St. Matthew Passion or playing the Goldberg Variations, how in heaven’s name would it be possible for any of us to favor any composer over Bach? Ditto when listening to Mozart’s Marriage of Figaro; a Beethoven Symphony; Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov;a Brahms Piano Quartet; Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde; Schubert’s Wintereisse; Haydn’s Creation; Verdi’s Otello; Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto; and a thousand-and-one other works by a hundred-and-one other composers. So much great music; so little time. How can we possibly choose favorites among such a wealth of extraordinary work?

On seemingly the same lines, I am also not-infrequently asked, “who is my favorite twentieth century composer?” Now: that is, in fact, a very different question. It’s a different question because starting around the first decade of the twentieth century, the vast majority of young composers began taking it upon themselves to create their own musical languages, partly if not wholly divorced from the melodic, harmonic, and formal traditions of seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth century tonal music.

Stylistic differences aside, Bach, Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, Wagner, Tchaikovsky, and Musorgsky all spoke the same musical language, albeit with different accents. When pushed, shoved, and/or entreated to choose a favorite composer among them, we’re endeavoring to choose whose particular use of that common language we prefer over the others. But in choosing a favorite among the composers of the twentieth (and for that matter the twenty-first) century, we’re actually choosing whose particular musical language appeals the most.

I am, personally, rather less promiscuous when it comes to the composers of the twentieth century than I am the composers of the “common practice” (the music of the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries). And while I’m generally loath to admit to “favorites”, there are two questions/criteria that, having been invoked, will indeed indicate who is my go-to twentieth century composer.

Question/Criteria one: for the sheer, visceral joy of listening, what twentieth-century composer’s music would I choose to listen to more often than not?

(This question speaks directly to what I consider the best advice a composition teacher can give his/her students: don’t waste your time writing music the likes of which you wouldn’t want to listen to recreationally.)

Question/Criteria two: speaking and thinking personally, as a composer, which twentieth-century composer am I most jealous of, meaning whose music do I wish I myself had written?

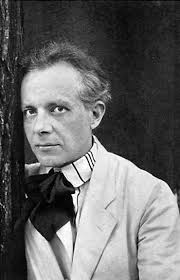

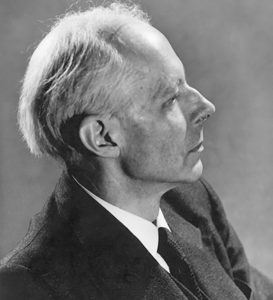

Based on my responses to these questions/criteria, my favorite twentieth-century composer would have to be the Hungarian Béla Bartók (1881-1945).