At its highest and ideal level, the purpose of art is to crystallize, summarize, epitomize and portray human experience in a manner universal and transcendent of its time and place of creation.

Some art is aesthetically beautiful and as such transports us to a “better” place, beyond this vale of tears that is our everyday existence.

Some art resonates with our own experience, and thus helps us to understand ourselves and our lives more clearly even as it inspires us to go on and fight the good fight that is our lives.

And some art delves into very dark places, places most “normal people” generally prefer not to go. We consume such art not because it entertains us; not because it is “attractive” in a traditional aesthetic sense but because it cuts to the bone of its subject matter and reveals truths – sometimes terrible truths – that are otherwise impossible to fathom or even describe.

Admittedly, such “dark art” forces us to feel and to comprehend – at a nonverbal, gut level – things that we might very well not want to have to feel or comprehend. But dreadfully trying though such art might be, we cannot turn away from it, so powerful is the message and its impact.

For example…

Caravaggio’s sado-erotic Judith and Holofernes “starring” Caravaggio’s favorite model, a courtesan/prostitute named Fillide Melandroni in the role of Judith, the Jewish heroine who seduces the merciless Assyrian general Holofernes and then kills him with his own sword. Caravaggio biographer Andrew Graham-Dixon describes the scene depicted by the painting:

“Once again, the painter brought a scene from the biblical past into the world of his own time, but never had he done so with such brutal, shocking immediacy. Sanctified execution in an Assyrian tent has become murder in a Roman whorehouse. The bearded Holofernes, lying naked on the crumpled sheets of a prostitute’s bed, is a client who has made a terrible mistake. He wakes up to realize he is about to die. Fillide pulls on his hair with his left hand, not only to expose his neck but to stretch the flesh taut so that it will part more easily under the blade. In her right hand she holds an oriental scimitar – Caravaggio’s one concession to historical accuracy – with which she has just managed to sever his jugular. She frowns with grim concentration as he screams his last, and as the blood begins to spray from the mortal wound in bright red jets. Caravaggio adds a sexual frisson to the thrill of bloody violence: beneath the diaphanous fabric of her tight-fitting bodies, Fillide’s nipples are visibly erect. A theatrical swag of dark red drapery hovers directly over the act of murder.”

It is a ghastly image, and yet we cannot tear our eyes away from it.

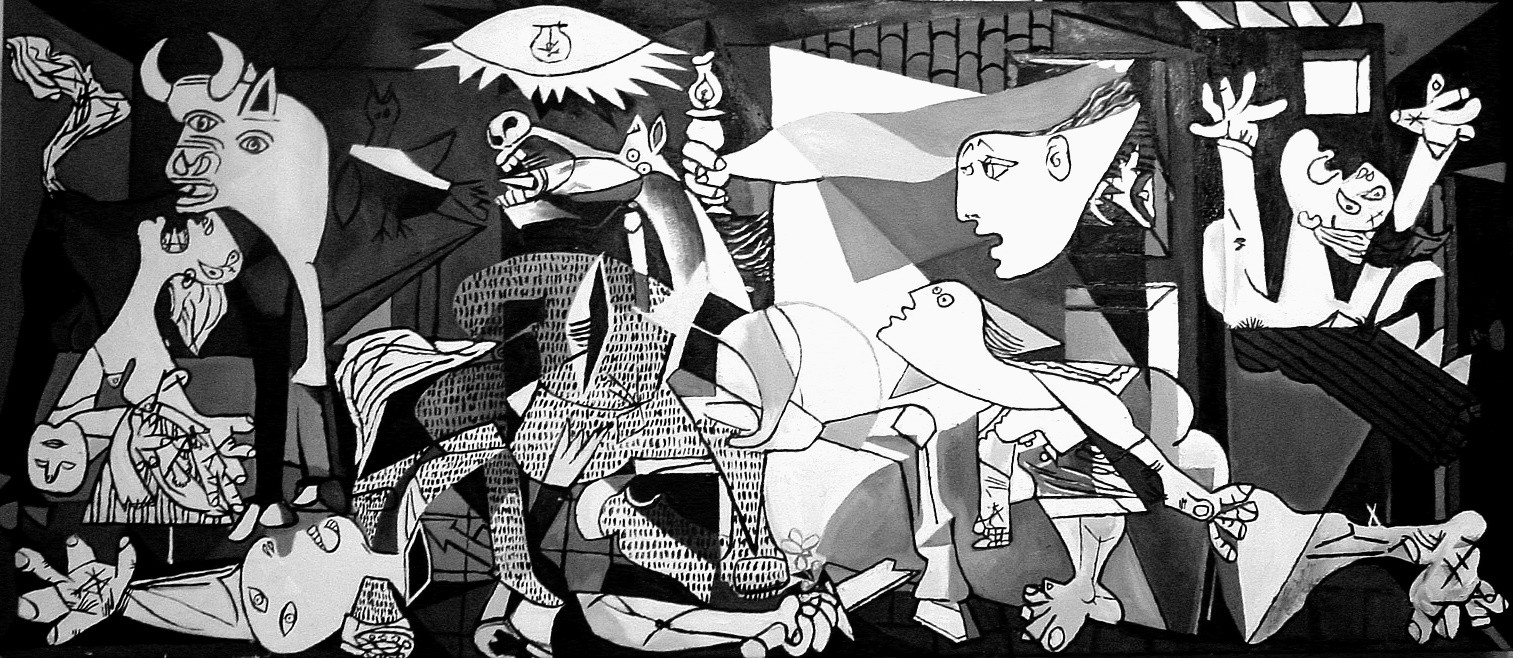

The same can be said for Picasso’s anti-war, anti-Fascist painting Guernica (1937), which commemorates the Nazi terror bombing of the Basque village of Guernica during the Spanish Civil War. Painted essentiually in black and white, it is a huge, mural-sized work: 11’5” (3.49 meters) tall and 25’6” (7.76 meters) wide. Guernica’s lack of color gives it a black and white, photographic feel, and thus the character of a report, of something that happened. Picasso entrusted the painting to the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York City which was instructed not to return the painting to Spain “until liberty and democracy had been established in the country.” Growing up, I saw Guernica many, many times at the MoMA, where – despite my tender years – it had a singular impact on me. It was returned to Spain in 1981, and can be seen today at the Museo Reina Sofía, Queen Sofía Museum in Madrid.

This list of great “dark art” could go on forever; the etchings and paintings of Goya; the paintings of Hieronymus Bosch, Edvard Munch, Otto Dix, George Grosz, and Francis Bacon. In literature, from Dante’s Inferno to Bret Easton’s American Psycho. Movies like Stanley Kubrick’s Clockwork Orange (1971) and Patty Jenkins Monster (2003) remain like thorn in my brain: movies that made an incredible impression but that I would never want to see again (thanks primarily to the amazing performances of Malcolm McDowell as Andre DeLarge in the former and Charlize Theron as Aileen Wuornos in the latter).

This all-too-lengthy preamble is intended to provide some context for Arnold Schoenberg’s A Survivor from Warsaw.

Last week, in my Music History Monday post on the death of Felix Mendelssohn, I briefly noted that November 4, 1948 marked the 71st anniversary of the premiere of Schoenberg’s A Survivor from Warsaw for narrator, chorus and orchestra. At the conclusion of that brief mention I wrote that for an expressive pop-in-the jaw:

“nothing can match A Survivor from Warsaw. I exaggerate not: this seven-minute, 99 measure-long piece has the impact of a thermonuclear device. In my humble but not ill-informed opinion, it is the most gut-punch powerful, harrowing, heartbreaking and inspirational work composed during the entire twentieth century.”

Let’s take a look at this remarkable piece, with the understanding that like Judith and Holofernes and Charlize Theron’s performance in Monster, A Survivor from Warsaw is not the sort of artwork we will turn to for entertainment or amusement.… Continue reading, and see Dr. Bob’s “must-have” recording of the work, only on Patreon!