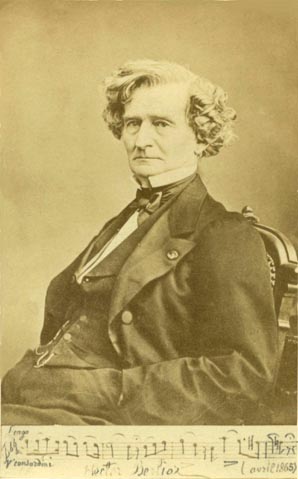

We mark the death on March 8, 1869 – 152 years ago today – of the French composer and conductor Hector Berlioz, in Paris at the age of 65. We will use this anniversary of Berlioz’ death for a two-day Berlioz wallow. Today’s Music History Monday post will frame Berlioz as a founding member of the Romantic movement and will tell a wonderful story that conveys to us much of what we need to know about Berlioz the man: his passion, his impulsiveness, and in the end, his good sense. Tomorrow’s Dr. Bob Prescribes post will delve more deeply into his biography and his proclivity for compositional gigantism, using his Requiem Mass of 1837 as an example.

Background: The Romantic Era Cult (really, fetish) of Individual Expression

An idealized image of the middle-class “individual” dominated the thought and art of the second half of the eighteenth century, a period generally referred to as the Enlightenment and, in music history, the Classical Era. This Enlightenment elevation of an idealized “individual person” saw its political denouement in the French Revolution (1789-1795) and its musical denouement in Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) and the subsequent Romantic era cult of individual expression. Whereas Classical era composers saw themselves as servants to their audiences and patrons, the post-Beethoven, nineteenth century Romantic era “artistes” saw themselves as creative heroes, beholden to nobody but themselves, free spirits, responsible only to their “muse”. When Franz Liszt declared that “my talent ennobles me”, he spoke for an entire generation of composers, who believed that God and nature had endowed them with a gift and a vision that deserved to develop free of restraint. Generally but accurately speaking, these nineteenth century Romantic composers believed entirely in the meritocracy, that “their talent ennobled them”.

Hector Berlioz, who was born on December 11, 1803 (five days before Beethoven’s 33rd birthday) was the “wild man” of Romanticism: a larger-than-life personality who believed with the passion of a Biblical zealot in the cult of individual feeling and magnified expression we have come to identify as the Romantic impulse. He composed some of the most expressively over-the-top music of the nineteenth century. His first major work remains his most famous: the groundbreaking Symphonie Fantastique of 1830.

Berlioz grew up the pampered and spoiled eldest child of a well-to-do doctor in southeast France. He was essentially self-taught as a musician, and as the saying goes, the problem with auto-didacts (the self-taught) is that they have lousy teachers. Having said that, Hector Berlioz was that one-in-a-million for whom a lack of formal musical education was a blessing. Never having been taught the “right” way to do things, his imagination was left free to go wherever it wanted, unhindered by pedantic, disapproving teachers.

Berlioz’ genius did not become apparent until his mid-twenties and consequently, he must be considered one of the great musical late-bloomers of all time. Unfortunately, he never entirely recovered from the insecurity caused by his lack of an early and “proper” musical education, and it’s likely that his often outlandish behavior and aggressive, “I-am-an-artiste” persona were at least a partial cover for that insecurity.…

Continue reading, only on Patreon

Become a Patron!Listen on the Music History Monday Podcast

Podcast: Play in new window

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Pandora | iHeartRadio | RSS | More