Two seemingly disparate events on this date provide the framework for today’s post. Here they are:

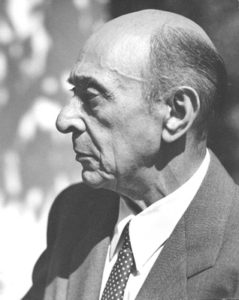

On July 13, 1951 – 69 years ago today – the composer Arnold Schoenberg died in Los Angeles. Born in Vienna on September 13, 1874, the date and timing of Schoenberg’s death could not possibly have been more ironic. You see, for most of his life, Schoenberg suffered from a fear of the number “13”, something called “triskaidekaphobia” after the ancient Greek word for the number thirteen. He suffered as well from the associated condition called “paraskevidekatriaphobia”, which is ancient Greek for “Fear of Friday the 13th.” Well, not only was Schoenberg born on the 13th day of the month (of September) and not only did he die on July 13th, but July 13th 1951 was a Friday. Schoenberg’s age at the time he died was 76; 7+6 = 13. All we can say is yikes.

The other event behind today’s post took place on this day in 1999, 21 years ago today. That was the day – according to THISDAYINMUSIC.COM – that an exhibition of 73 paintings by Paul McCartney opened to the public at the Kunstforum Lyz gallery in the German city of Siegen, about 40 miles east of Cologne. (Other, perhaps more reliable sources peg the exhibition as taking place from May 1 to July 25, but we’re going to go with the date published by THISDAYINMUSIC.COM because it’s just so damned convenient to do so.) McCartney (born 1942) began painting seriously in 1983. The paintings he exhibited in Siegen (three of which, all painted in the 1990s, are pictured below) reflect a serious Viennese Expressionism vibe.

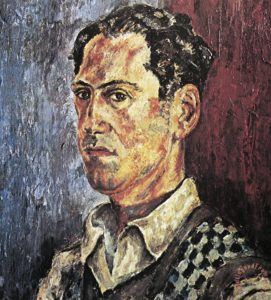

Arnold Schoenberg was not just a visionary composer but a visionary painter as well. He created his main body of paintings between 1906 and 1911. Schoenberg’s paintings do not just “reflect” a serious Viennese Expressionism vibe; they are an integral part of the Viennese Expressionist movement as it evolved in the first years of the twentieth century! Schoenberg was on intimate terms with many of the greatest painters of the period: Egon Schiele, Oskar Kokoschka, Gustav Klimt, Richard Gerstl (who had an affair with Schoenberg’s wife!), and Wassily Kandinsky. In 1912, Kandinsky wrote of Schoenberg:

“Just as in his music, Schoenberg also in his painting renounces the superfluous and proceeds along a direct path to the essential.”

The three, haunting self-portraits below – all painted in 1910 – attest to Kandinsky’s words. They also attest to the fact that stylistically and expressively, as painters, Arnold Schoenberg and Paul McCartney are nothing less than soul mates!

In 1910 – the year those three self-portraits were painted – a nameless Viennese art critic opined:

“Schoenberg’s music and Schoenberg’s pictures: that will knock your ears and eyes out at the same time!”

Schoenberg and McCartney are not the only high-end composers/songwriters to have been accomplished painters. Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847) was a highly skilled visual artist who left behind more than 300 drawings, watercolors, and oil paintings.

Ronnie Wood (born 1947), guitarist for the Rolling Stones, has been drawing and painting since he was 12; his art has been exhibited at the Butler Institute of American Art in Youngstown, Ohio. David Bowie (1947-2016) painted for most of his life, though he didn’t go public with his visual art until 1994.

Patti Smith is a superb visual artist, who by her own admission “dreamed of being a painter.” In 2002, a three hundred-work retrospective entitled Strange Messenger: The Work of Patti Smith, was organized by the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

The list of composers/songwriters that have created significant bodies of visual art goes on, including Bob Dylan; Marilyn Manson (who in 2002 told Rolling Stone “they might expect me to have painted in my own shit or something,” when discussing the critical reception of his debut exhibition, The Golden Age of Grotesque, at Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions); John Lennon (who attended art school); and Joni Mitchell (who once said that: “I’m a painter first, and a musician second”).

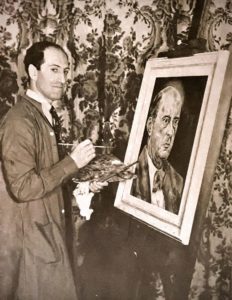

But as composers-slash-songwriters-slash-painters go, we give final pride-of-place to George Gershwin (1898-1937), who will bring this post a full circle.

We read that as children, both George and his older brother Ira (1896-1983) were “avid doodlers.” (I’m not frankly sure what this means. Did they draw actual pictures of people and things? Did they spray-paint graffiti on local garage walls? Did they draw nasty stuff in the margins of their textbooks? )

Whatever they drew, George’s continued impulse to draw prompted Ira to suggest – in 1927 – that he – George – take up painting. George Gershwin generally (and wisely) did what his bro suggested (It was Ira who suggested the title “Rhapsody in Blue” back in 1924), so he gave painting a try. He started with watercolors, quickly progressed to oils, and discovered that he had a real talent for it. And that talent was immediately and properly nurtured, as it just so happened that George’s cousin was the noted modernist painter Henry Botkin (1896-1983). Botkin took George under his wing, and he rapidly developed into an accomplished artist. (Botkin also helped Gershwin put together what has been called “a world-class art collection”, one that would be worth many millions of dollars today.)

Gershwin liked painting people best, and his portraits garnered attention. An article in the January 1934 issue of Arts and Decoration asserted that:

“If his family had presented him with an easel and some paints when he was a child, instead of with a piano, he would be a professional painter today rather than a musician.”

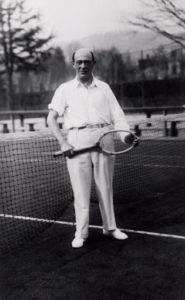

Along with the self-portrait above, Gershwin’s most famous portrait is the one he painted of his friend and tennis partner, Arnold Schoenberg, painted circa 1936/37.

The story behind Gershwin and Schoenberg’s friendship is one that simply must be told!

In August of 1936, George and Ira Gershwin – their first movie contract in hand – left New York City for southern California. Like the Clampett clan some years later they headed out to Beverly: Hills that is; swimmin’ pools; movie stars. They set up temporary digs at the Beverly-Wilshire Hotel, but soon rented a house at 1019 North Roxbury Drive (the so-called “Street of Stars”) in Beverly Hills. The house was appropriately palatial, and came complete with a swimming pool, tennis court, and a monthly rent of $800: the equivalent of $14,897.04 at the time of this writing (July 11, 2020).

Gershwin was immediately embraced as a star on the Tinsel Town social scene and he rubbed shoulders and partied with Hollywood’s elite. And among his best new friends and his regular tennis partner was the 62 year-old Arnold Schoenberg who lived at 116 North Rockingham Avenue, in nearby Brentwood Park.

Depending upon the source, Gershwin and Schoenberg played tennis together at Gershwin’s rental every Wednesday, or twice a week; some sources even say daily. Their tennis “group” included Groucho and Harpo Marx and Charlie Chaplin, and there’s not one of us who wouldn’t give a small toe to have been sitting courtside to witness that group of people lob tennis balls at each other. Gershwin’s friend, the composer, pianist, and gadfly Oscar Levant (1906-1972) was also part of the group, and he has left us with the following reminiscence:

“Tennis was second in [George’s] interest only to the piano. Even exceeding George’s passion for tennis was that of Schoenberg. The meeting of Schoenberg and Gershwin was an affectionate one and resulted, among other things, in a standing invitation for the older man to use the Gershwin court on a regular day each week.

On one occasion, after playing two vigorous sets, Schoenberg [was] driven from the court by a sudden shower. Schoenberg wiped his brow and said, half to himself, ‘Somehow I feel tired. I can’t understand it.’ Then added suddenly, ‘That’s right. I was up at five this morning. My wife gave birth to a boy.’

‘Why didn’t you tell us before?’ said George. ‘Come inside, we’ll drink a toast.’

We adjourned to the house, the glasses were filled, and George spoke touchingly of the event. As he was about to drink, George raised his glass and paused. ‘Why don’t you name him George? It’s a lucky name.’

Schoenberg shook his head wearily. ‘You’re too late. I already have a son named George.’”

We don’t know if Gershwin was familiar with Schoenberg’s own paintings, and we can only wish that Schoenberg had painted Gershwin. But we do know that Schoenberg praised Gershwin at every opportunity, and that he wrote a lengthy and touching appreciation of Gershwin after his sudden and utterly unexpected death, in Los Angeles, on July 11, 1938. (It was a brain tumor.)

Schoenberg wrote:

“It seems to me beyond doubt that Gershwin was an innovator. What he has done with rhythm, harmony and melody is not merely ‘style’. It is fundamentally different from the mannerism of many a ‘serious’ composer. He is an artist; he expressed musical ideas, and they were new – as is the way in which he expressed them.”

For lots more on Arnold Schoenberg and George Gershwin, I would call your attention to my Teaching Company/Great Courses survey, The Great Music of the 20th Century.

Listen on the Music History Monday Podcast

Podcast: Play in new window

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Pandora | iHeartRadio | RSS | More