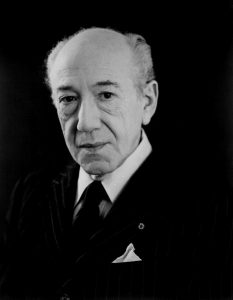

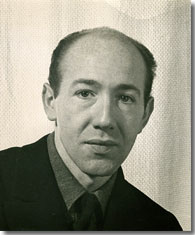

David Leo Diamond (1915-2005) composed eleven symphonies. When he died at 89 of congestive heart failure on June 13, 2005 in the Town of Brighten – located on the southeastern border of his native city of Rochester, New York – he left no family or heirs. A prolific composer, his greatest output are his songs, his ten string quartets and, most importantly, his eleven symphonies. Diamond was wont to refer to his symphonies as his “children”, and if that be so, then he did indeed leave family behind: lots of family. And unlike many of our families, filled (as they usually are) with all sorts of problematic individuals, there is not a single delinquent among Diamond’s “children”. Together they constitute one of the great symphonic legacies in the repertoire, taken as widely as we please.

So why is the name David Diamond so vague – even unrecognizable – to so many lovers of concert music?

A number of explanations have been put forth. Some say the blame lays with Diamond himself and his famously testy personality. In an interview conducted by the New York Times in 1990, the then 75-year-old Diamond admitted that:

“I had a reputation as a problem person. I was a highly emotional young man, very honest in my behavior, and I would say things in public that would cause a scene between me and, for instance, a conductor.”

(Okay; that was something of an understatement. For example, in 1943, the New York Philharmonic and its 25-year-old assistant conductor – Leonard Bernstein – was reading through Diamond’s Symphony No. 2 in Carnegie Hall. Diamond couldn’t keep his mouth shut, and after he’d heard enough, the Philharmonic’s music director – Arthur Rodzinski – had Diamond booted out of the building. Diamond retreated to the adjacent Russian Tea Room restaurant, where he proceeded to get drunk. Eventually, Bernstein and Rodzinski came in. Diamond – who could not have stood more than 5’4” tall – walked up to the much taller Rodzinski and punched him in the nose. Aside from being a politically unwise act, it was also a potentially fatal one, as Rodzinski was known to carry a revolver. On the flip side, we’re honor-bound to observe that Diamond’s personality notwithstanding, his music was championed by such marquee conductors as Leonard Bernstein, Serge Koussevitzky, Charles Munch and Dimitri Mitropoulos, none of whom received so much as a mild box on the ear from Diamond. We’d also recall that Beethoven not only tried to break a chair over the head of his principal patron, Prince Karl Lichnowsky but routinely verbally abused and threatened conductors, none of which pushed his music into obscurity.)

Some claim that Diamond’s eventual obscurity was the result of his being openly homosexual at a time when most gay folks believed that survival depended upon utmost discretion. But this is nonsense as well. Look: no mid-twentieth century composer was more openly gay than Benjamin Britten – 1913-1976 – and no one could ever assert that his homosexuality had any affect whatsoever on the phenomenal and ongoing popularity of his music.

The real reason behind Diamond’s increasing obscurity during the second half of the twentieth century was musical politics, pure and simple: a move, particularly in American academia, away from compositional populism and towards ultra-modern, typically ultra-unlistenable serialism. In Diamond’s obituary, the New York Times observed that:

“He was part of what some considered a forgotten generation of great American symphonists, including Howard Hanson, Roy Harris, William Schuman, Walter Piston and Peter Mennin.”

We here at Dr. Bob Prescribes are doing our best to remember that “forgotten generation”, as every one of the composers named by the NYT in Diamond’s obit has thus far been profiled in this post. Today – obviously – it is Diamond’s turn. …

See the profile and recommended work and recording, only on Patreon!